by Carly Racklin

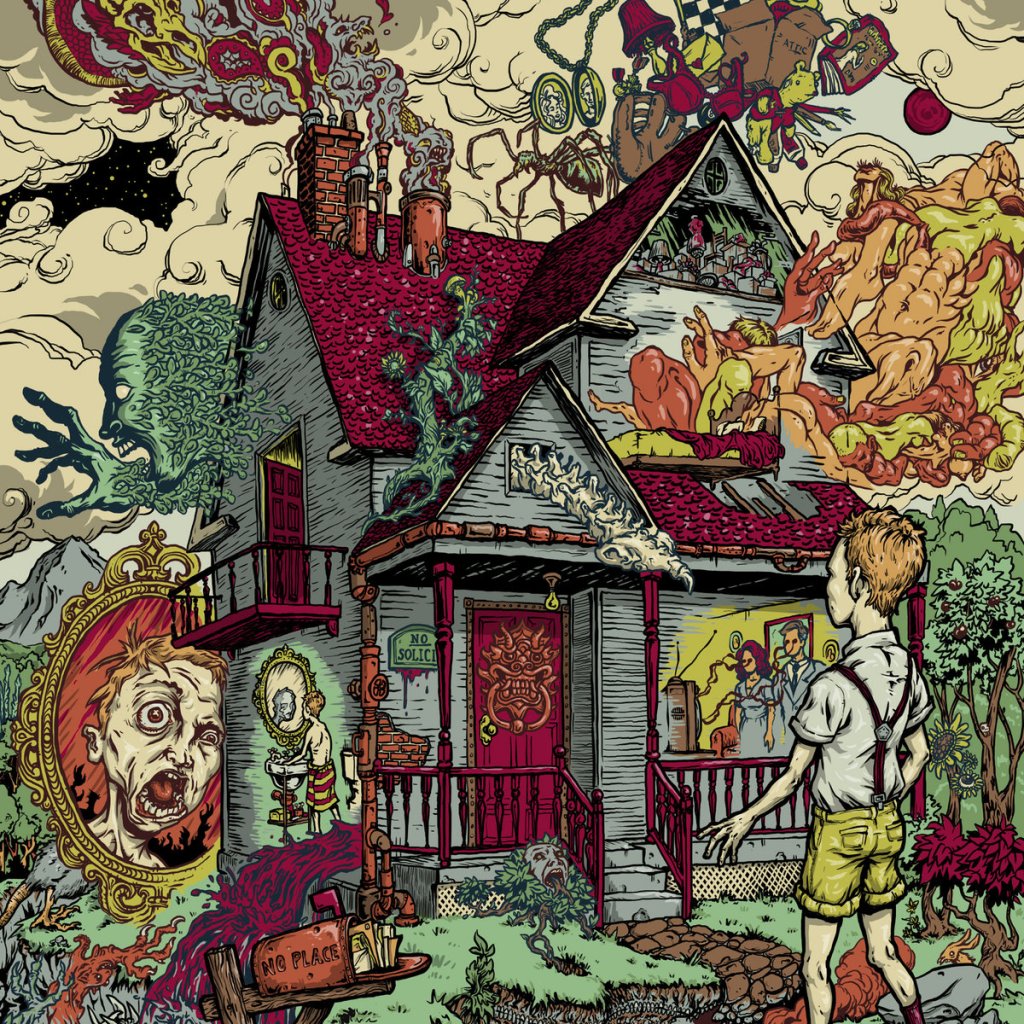

“The sign above the door says no solicitors, whereas the vines along the wall scream no visitors at all; family, friend, stranger or otherwise.” These lyrics open the 2013 album No Place by post-hardcore band A Lot Like Birds. The home in No Place was, like many haunted houses before it, left abandoned for one reason or another. Its paint has peeled, its foundations sunken low in the earth, its beams home only to hungry scavengers. Festering and forgotten, the house has grown vicious. It has grown teeth. This house is more than fit for the warning given in Kitty Horrorshow’s beautifully brutal game Anatomy: “When a house is both hungry and awake, every room becomes a mouth.”

No Place follows the movements of a narrator within a house they previously called home. Each of the ten tracks represents a specific location in the house: front doorway, basement, living room, bathroom, hallway, closet, bedroom, balcony, attic, and the room with no purpose (unique to every family). The album does not ask us to consider whether or not the house is haunted. We know it is. We’re prompted to dig deeper, asking instead: if the root of a house is love, what happens when the root rots? When both apple and tree are left to the worms? A haunted house is its own organism, a theme similarly explored in Anatomy. You feed a home your vulnerability and expect to be understood and accepted in return. Families and houses grow together. The house knows that the place where you are most understood is also the place where you are most vulnerable. Though we learn the narrator “loved [the house] deeply,” that memory is not enough to cure the trauma and betrayal the house has suffered in its abandonment. Critically, the house in No Place is haunted because it was beloved.

In the first track “In Trances,” we are enticed by the melody of a welcoming doorbell, beckoning us to explore alongside the curious narrator who only enters through a window, recognizing themselves as an intruder in a place once familiar. The guitar’s tone shifts, suddenly dissonant as the narrator becomes trapped, and the architecture turns hostile:

The window always stuck in odd ways when I tried to exit through it

It asked me questions,

“If the eyes are the window to the soul, why do you only feel alive when they are closed?”

And then something else took hold, and the window broke

Though traditionally, it is people who own houses, the identity of the album’s house has been corrupted; it has become a flytrap of familiarity, possessive of its former occupant.

“No Nature,” the album’s second track, throws the listener into one of the most commonly feared places in a house, the site of many a horror-movie bloodbath and ghostly jumpscare: the basement. The lyrics inform outright that, “the devil runs this hole.” Both instrumentally and lyrically, the song is jarring and chaotic, as the narrator’s paranoid brain is hounded by a cacophony of demonic voices, those who have taken over in their absence:

And hey, who can blame you for wishing? (Give it up!)

Hope’s probably the last thing any of us can take from you. (Stop!)

But we’ll get there eventually. We take everything.

Why’d you even come back in the first place? (Turn! Back!)

This isn’t your home anymore. It’s mine. It’s ours. (Leave.)

“Everything you lost watches closely,” the spirits drone, highlighting that though the memories made in a house may take on a life of their own, we are the root.

It is common in many haunted house stories to see generational trauma depicted as the seed that begets ghosts. An atrocity is so horrible that its damage becomes physical, and takes on a presence that can be experienced by all, not just the one who originally suffered it. “No Nurture,” track three, explores this idea through the setting of the living room. “All I really wanted was this home,” laments the narrator, the victim of an emotionally and physically absent father. The song ends with the damning question: “They say ‘like father, like son’ / Is that the reason that every time a person loves me I find it hard to love them back?” Make no mistake, a broken home is just another name for a haunted house.

The bathroom in “Next to Ungodliness,” offers a short reprieve, a moment of privacy in which the narrator must look inward, wondering, “Is there anything worth keeping?” They leap, instead, to a shallow sort of acceptance in the name of self-preservation: “I know you keep pretending / Let me be the same.” But the house does not want their acceptance; it is aggrieved and wants the narrator to suffer as it has. The fifth and middle track on the album, “Connector,” represents the hallway bridging the disparate rooms and hurts: “dark and narrow / That we pass through like marrow through bone.” Lyrically, it touches on the themes of the other rooms while acknowledging how the house, like the relationships it once upheld, has fallen into disrepair:

And now we sit in what was built on our dreams

A space, now sad, speaks madness, attempts concealing

The crumbling walls

It feels like our time is getting short

And it’s too late cause all the paint is lying on the floor

“Connector” toes the line between nightmare and reality, jumping between different tempos and time signatures, throwing the narrator and listener through disorienting scenes reminiscent of the childhood nightmares we hid from under bedsheet armor.

Out of the corner of my eye

I see the ghost stutter-stepping like strobe lights

Ever-inching closer, but always out of reach

So I hold my breath and keep it under my tongue

And wait until both of my lungs are filled

If I count to ten, will it all go away?

This horror cannot be escaped; over and over, we’re reminded, “We all fall apart.” And over and over, we’re told that nothing buried has stayed dead:

Always colliding with the things that we had tried hard to avoid

We just bury them, close our eyes, cover it up

But what was buried managed to unlock the door

Even though we had boarded them, nailed them shut, hid the keys

Track six, “Myth of Lasting Sympathy” is a time capsule in a monologue, one that takes us to the closet, a childhood haven from monsters and nightmares. That innocence has since slipped through the narrator’s fingers; they understand in hindsight that cruelty is home-grown, and our hauntings are in fact self-made:

In the stories we want told to us before we fall asleep, the heroes are ideals that never get reached

And the villains are absolutely ordinary

And we are absolutely ordinary

And you stare back at me through the closet and into the world that I never really changed

And ask me the only thing you want to know

“When we grow up, do we still get scared when the lights go out?”

The next track, “Hand over Mouth, Over and Over,” takes place in the bedroom. Slow, building, and balladic, this song offers another reprieve in the shelter of a teenage bedroom, where the narrator yearns for lapsed relationships. Infected by the house’s loneliness, they wonder, “Will the good parts stay in limbo?” Pull the covers over your head and breathe, this track urges; it will all be over soon. Morning will break and the monsters under the bed will return to where they came from. The house convinces you to stay, that it is safe here. And it was, once. Not every memory in a haunted house is bitter — there would be no tragedy otherwise.

“Kuroi Ledge,” track eight, is the loneliest of the album. Musically, it’s gentle and melancholic, and calls to mind a mourning Heathcliff’s famous quote in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights: “Be with me always—take any form—drive me mad! only do not leave me in this abyss, where I cannot find you!” In “Kuroi Ledge,” the narrator makes a similar demand:

I’m still here

I know you’re waiting for me past the doorway

And if it’s you that’s haunting me, say something

And if it’s you that’s haunting me, say something

If it’s you that’s haunting me, just speak

With hope dwindling, the house attempts to lure the narrator to join in its deathly deathlessness, telling us: “The call of the void is coming from the balcony.”

Mirroring the second track on the album, the second to last, “Recluse,” takes us to another oft-feared room: the attic, where another chorus of creatures, in this case referencing deadly brown recluse spiders, has made a home of the family’s detritus and memories. The attic is where memories often are left to rot, but rotting doesn’t mean dead, and dead certainly doesn’t mean gone. The house has never forgotten. The house can’t forget — why should you be allowed to? “Home is where the hearts are,” we’re told. In the next line, the saying corrupts further and becomes “Home is where the fun starts.” Both claims bear the attribution: “said the hunger to the waiting predator.” The particular demon of this track casts the narrator out, hearkening back to the assertion in “No Nature” that this house doesn’t belong to them anymore: “Don’t stay. I don’t care, just let me be or make me whole / Walk, crawl, run. As long as you don’t forget this place, our faces, these old floors.” The track concludes with the predator’s call to arms: “I know where to go. Go for the throat.”

The final track, our dénouement is “Shaking of the Frame.” Hunted, the narrator runs for the exit, repeating a refrain of, “Just let it go.” Meanwhile, the house has poisoned their thoughts with the desire to submit to their history, to stay where they belong, where they are understood: “And the ever-chugging monolith, my inner voice, is inviting me to stay here for years / I’m wired weird, I’ve grown wrong.” Homes so often become reflections of ourselves: our passions, yes, but our fears and insecurities too. In this way, the narrator and house are symbiotes. They’ve shaped each other inextricably.

Interestingly, “Shaking of the Frame” represents a room in a house with no specific purpose, maybe a dining room to one family, or a dusty guest room to others, but its purposelessness is integral. The fruit of such emptiness is want, loneliness, and all the trauma of the previous tracks. “May the room with no purpose forever be closed,” prays the fleeing, desperate narrator. And by a miracle, their prayer seems to be answered. About two-thirds of the way through the track, a calm descends, triumphant horns sound, and the narrator finds the strength to escape the house, which finally collapses under the weight of its ghosts. But though a house may crumble, it cannot die.

Although we left in a panic

I took a look back at the house

Saw it turn on its axis and vanish

The dust enveloped the sky, the splinters fell to the earth

Swam deep in the soil and came back to life

It survived, it survived, it survived.

The narrator’s exit at the end of No Place is not a true escape. After all, what is freedom, when you bear the haunting in your bones, in your blood? Like countless other tales of haunted houses, No Place only reminds us what we already fear to be true: that roots run deep. The past is never dead. It crawls its way to the light no matter how deep we bury it, crush it, or run from it. It survives, it survives, it survives.

Carly Racklin (she/they) is a writer, editor, and vulture enthusiast with a passion for the fantastical and visceral. Her work has appeared in The NoSleep Podcast, Haven Spec Magazine, Frozen Wavelets, and more, and her debut novella FUNERAL SONG is forthcoming from Dead Sky Publishing. In addition to her fiction, she has written for an international horror film festival and an indie roleplaying game publisher. She can be found on most socials @willowylungs and at carlyracklin.com.

Leave a comment