by Jennifer Smith

Despite the criticisms Stephen King faces for his portrayal of women in his works, I argue that his characters Beverly Marsh, Carrie White, Jessie Burlingame, and Dolores Claiborne stand as multigenerational examples of defiant and resilient women who navigate and dismantle oppressive patriarchal systems, thereby underlining the enduring strength of women amidst adversity. Through the

lens of Julia Kristeva’s theory of the abject, this article examines the ways in which Beverly, Carrie, Jessie, and Dolores transgress and subvert patriarchal sanctioned borders, positions, and rules in order to break free from their abusers. In these four characters, King highlights the courage and strength that reside within oppressed women of multiple generations and time periods.

In King’s 1986 novel It, he explores fear, hatred, and violence in the fictionalized small American town of Derry, Maine, revealing how white patriarchal ideology can turn ordinary individuals into monsters. One such monster is Al Marsh, Beverly’s abusive father. Beverly experiences both physical and verbal abuse at the hands of her father, with indications that sexual abuse either has or will occur. Pennywise, playing on Beverly’s fear of her father and her anxiety about approaching womanhood, terrifies her by flooding

her bathroom with blood, which symbolizes menses and the passage from girlhood to womanhood. When a terrified Beverly calls out for help, her father enters the bathroom but does not see the blood.

Because Beverly knows she will be subject to abuse if she attempts to explain the blood-soaked bathroom to her unseeing father, she blames her fright on a spider; nevertheless, Al beats Beverly anyway. Immediately after the beating, Al tries to play the role of a loving father through performative acts such as kissing Beverly on the forehead and tucking her into bed. This sudden shift in her father’s

behavior confuses Beverly and contributes to her anxieties about relationships with men. Yet, despite her apprehension, Beverly relates her experience in the blood-filled bathroom to the fellow members of The Losers Club. In contradiction to her father’s reaction, the boys in The Losers Club believe Beverly when she tells them about her blood-soaked bathroom. They volunteer to help her clean bathroom, thereby demonstrating their willingness to be a safe place for Beverly as she works through her trauma.

This is a moment of healing for Beverly, as she discovers that relationships with men can be built on mutual love and trust.

With this context in mind, the acts of physical intimacy that take place between Beverly and the other members of The Losers Club demonstrate her empowered view of womanhood and her trust in the relationships she has built with her fellow Losers Club members.

After defeating Pennywise, the young members of The Losers Club are lost in the sewer. Beverly realizes that – in order to escape – they must find a way to reconnect. It is Beverly who decides that connection through physical intimacy is the key to their escape. Reinforcing Beverly’s agency in this decision, the scene is written from her perspective: “She feels powerful . . . is this what her father was afraid of? There was power in this act . . . a chain-breaking power that was blood-deep.” Embracing an empowered view of womanhood and sexuality, Beverly breaks free from her father’s indoctrination and abuse and secures freedom for herself and the other members of The Losers Club.

In the 1974 novel Carrie, King “explores women’s empowerment and societal fears regarding female sexuality” through the lens of titular character Carrie White. Like Beverly, Carrie embodies a liminal space between girlhood and womanhood. Additionally, both Carrie and Beverly experience parental abuse and anxiety about the changes taking place in their bodies as they reach the stage of

womanhood. At the beginning of the novel Carrie, Carrie White experiences fear of the abject – specifically a fear of menses – when she experiences her first menstrual period in the girls’ locker room shower of her high school. Because her mother Margaret never explained the menstrual cycle to her, teenaged Carrie has no idea what is happening to her body; thus, her initial reaction is one of terror. Carrie is further traumatized by her peers who yell “plug it up” repeatedly while they throw pads and

tampons at her.

Carrie has been subjected to lifelong abuse from her overly zealous religious mother Margaret; yet, Margaret is part of a larger system of abuse stemming from misogynistic religious views and patriarchal ideology. However, as Carrie embraces her emerging womanhood and growing power, she challenges her mother’s beliefs and societal constraints, asserting her autonomy with the declaration, “‘My will, Momma.’”

Carrie’s level of retaliation against her oppressors is equal to the level of torment she has experienced throughout her lifetime. No longer cowering in fear, Carrie revels in her newly awakened power. In her final moments, Carrie channels her pain into a power-filled dismantling of the systems and individuals who have long suppressed and abused her. By overcoming her own internalized misogyny and fear, Carrie becomes a catalyst for disrupting abusive patriarchal systems, even though she herself does not survive.

King’s 1992 novel Gerald’s Game delves into societal issues like abuse and anti-feminism.

Like Beverly Marsh and Carrie White, this novel’s protagonist Jessie Burlingame has also experienced parental abuse. The trauma from Jessie’s father’s sexual abuse follows her into adulthood, yet she represses this memory until she is forced to confront it in order to save her life. In the novel, Jessie and husband Gerald have gone away to an isolated cabin for what is supposed to be a romantic getaway. While at the cabin, Gerald handcuffs Jessie to the bed and then attempts to rape her, as Jessie clearly does not consent to Gerald’s acts and demands that he remove the cuffs. However, he refuses to do so. Jessie then kicks Gerald. As a result, he falls to the floor and suffers a fatal heart attack. This confrontation with Gerald triggers memories of Jessie’s past abuse, which had been suppressed in her subconscious.

Left alone and handcuffed to the bed, Jessie makes a conscious decision to fight for her life, confronting both her past and present trauma. In order to free herself from the handcuffs, Jessie pierces her wrist with a shard of glass. Jessie’s self-inflicted injuries, including degloving, release her from physical restraints, symbolizing her liberation from patriarchal oppression, guilt, and internalized misogyny.

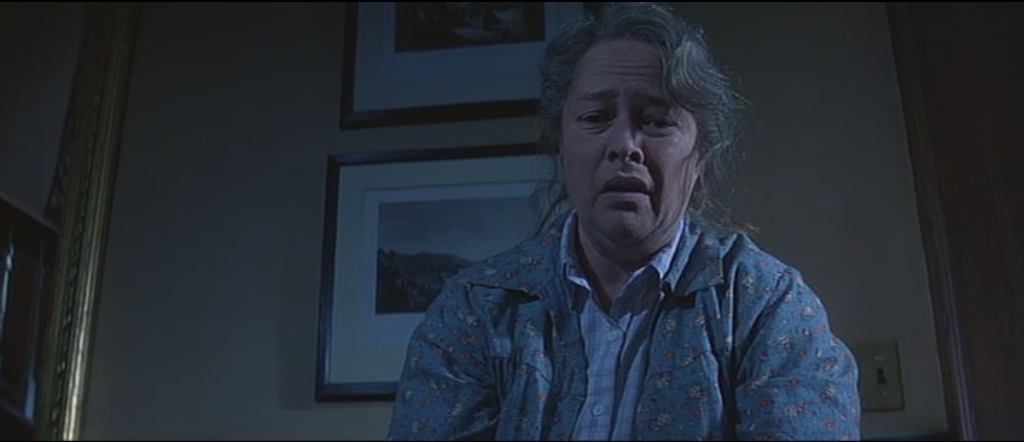

Like Jessie, the titular character in Stephen King’s 1992 novel Dolores Claiborne is married to an abusive man. Furthermore, like Jessie’s father, Dolores’s husband Joe sexually abuses his preteen daughter Selena. In the character of Dolores, King illustrates the limited options women face when confronting domestic violence. Dolores, unable to depend on support from her neighbors, the police force, the courts, the bank, and other societal institutions, turns to her older wealthy employer Vera Donovan for help. The two women form an unlikely alliance, thereby serving as an example of multigenerational connection between two women from different socioeconomic backgrounds. At Vera’s suggestion, Dolores formulates a plan to ensure that her husband Joe has a fatal “accident” on the day of the upcoming eclipse.

Additionally, this eclipse serves as a connection between the novels Dolores Claiborne and Gerald’s Game. During the eclipse, as Dolores sets her plan to kill Joe in motion, she and preteen Jessie have mutual visions of one another. Dolores sees Jessie in her father’s lap, while Jessie sees Dolores make her husband “fall down the well”.

Dolores’s unwavering belief in Jessie’s survival reflects their bond, as Dolores states, “‘I thought of how it’d crossed my mind that the woman she’d [Jessie] grown into was in trouble. I wondered how she was n where she was, but I never once wondered if she was . . . I knew she was. Is.’” Despite being silenced and neglected by those meant to protect them, Dolores and Jessie forge their own system of female empowerment, breaking free from patriarchal oppression and ending cycles of abuse.

Beverly Marsh, Carrie White, Jessie Burlingame, and Dolores Claiborne serve as examples of multigenerational women who bravely defy oppressive patriarchal systems, inspiring readers to stand against abuse. As readers examine each of these four women, King’s words in It resonate: “Be true, be brave, stand.” Like Beverly, Carrie, Jessie, and Dolores, today’s women must continue to push back

against the darkness of oppression in order to light the way for future generations of empowered women.

References:

- Canfield, Amy. “Stephen King’s Dolores Claiborne and Rose Madder: A Literary Backlash Against

- Domestic Violence.” The Journal of American Culture 30, no. 4 (2007): 391-400.

- King, Stephen. Carrie. New York: Anchor, 2013.

- —. Danse Macabre. New York: Berkley, 1983.

- —. Dolores Claiborne. New York: Gallery, 1993.

- —. Gerald’s Game. New York: Signet, 1993.

- —. It. New York: Signet, 1987.

- Kristeva, Julia. The Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. Translated by Leon S. Roudiez. New York:

- Columbia University Press, 1982.

- Smith, Jennifer. “Eclipsing the Patriarchy: The Power of Intergenerational Female Connection in Stephen

- King’s It, Carrie, Jessie’s Game, and Dolores Claiborne.” SNHU Master’s in English Capstone Project,

- September 5, 2023.

Jennifer Smith (she/her) holds a MA in English from SNHU and was a presenter in the Stephen King Area

at the 2024 Popular Culture Association National Conference. You can find her reading, watching, and

discussing the horror genre at https://www.instagram.com/literarylove123/

Leave a comment