by Payton McCarty-Simas

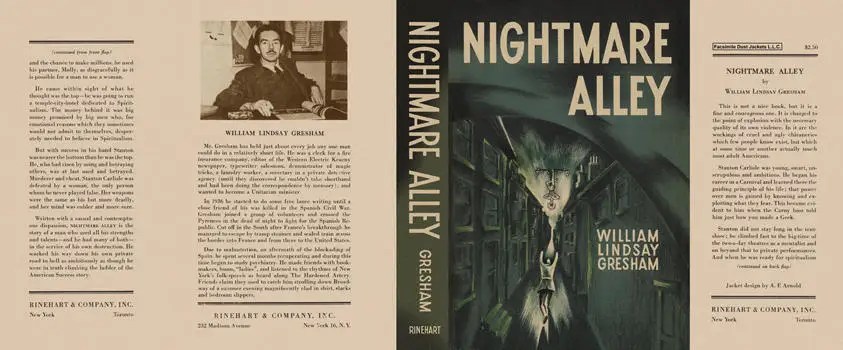

Nightmare Alley is a rich exploration of the tormented gulf between superstition and science in a particular time and place. This noir fairytale dwells on life on the shadowy fringes of the harsh, quotidian, not-as-modern-as-you’d-think world of early 20th century America. In an era when the lines between fiction and fact were being redrawn anew by science, politics, and religion, the seedier denizens of these dark corners practice (and often believe) both and neither, throwing questions of faith and destiny into doubt. Through canny deployment of the tarot as a sort of hinge between the divine, the arcane, and the Freudian, the original William Lindsay Gresham novel posits that the distance between scientific belief and superstition is smaller than either doctors or carnies would like to believe. In its bleak outlook on questions of “fate,” be it predestined by Freudian psychoanalysis or by God’s plan, the book and its two subsequent film adaptations–– the most recent of which went on to garner four Oscar nominations including Best

Picture in 2021–– have fascinated generations of audiences. While each version is different, and these differences alter its fundamental message, the overall story’s brilliance lies in this careful balancing act, turning a winding neo-noir into a work of occult horror.

Tempting Fate: The Novel

“Is he man or beast?” a seasoned barker asks a crowd of morbidly fascinated lookers-on as a carnival “geek” bites the heads off live chickens. For Stanton Carlisle–– William Lindsay Gresham’s antihero, a young upstart magician who will stop at nothing to escape the deprivations of life as a drifter and exchange them for fame, fortune, and the American Dream–– the answer is beast. Over the course of the book, this hardscrabble orphan shamelessly preys on the needs of others, and loves every second. Briefly put (though summarizing the story’s complex, tangled, and heady plotline was admittedly a challenge both films struggled to overcome) as he drifts from woman to woman, Stanton learns the tricks of the carnival trade. First swindling valuable “mentalist” tricks and “codes” from Zeena, an older mind reader down on her luck (“accidentally” killing her alcoholic husband Pete in the process), he then ruthlessly exploits Molly, the young wife with whom he replaces her to polish his act, becoming Stanton the Great and performing readings blindfolded in lush ballrooms. He learns to play with people’s belief, their psychology, through archetypes that could be read as Freudian or Pagan in origin. In one poignant scene, Pete gives Stanton a seemingly deep cold reading of his past, only to reveal that it’s a “stock” assessment: “every boy has a dog,” he laughs. No matter the particular “code”

one uses, the feelings that animate them are universal.

David Straithan, Toni Collette and Rooney Mara in Guillermo Del Toro’s film adaptation of Nightmare Alley (2021) Searchlight Pictures

Still, inevitably molded though he is by his own past experiences (his psychology, God’s divine plan, or the winds of fate), Stanton’s arrogance leads him to feel that he’s above the fray of petty human emotion. He works to master the game on others just to flip the whole table away from himself. Ignoring the warnings of his two carney lovers who tell him that he’s tempting fate (Zeena with her tarot deck) or trying God’s patience (Molly with her unvarnished love), he eventually gains enough notoriety as a nightclub act to start a swindle as a Spiritualist medium for Chicago’s wealthiest, only to have a sleek young psychologist named Lilith headtrip him out of his profits and back to the gutter, broken and alcoholic. Without prospects, love, or faith in himself or a higher power, Stanton agrees to geek for a carnival indistinguishable from the one where he started his act. The story is a bleak one, written by a man who would eventually commit suicide in the same hotel where he penned his tale of irreparable human isolation. By its conclusion, each of the three previously disparate branches of what in medieval times would have been viewed as “science,” (magic, religion, and medicine) have been rendered strange, desperate, and, fundamentally, occult.

How To Read Minds

Early on in Stanton’s sly quest up the antisocial ladder of various grifts, the carnival barker explains to him that the debased geek is a creature who is made, manifested and shaped from the dregs of a man whose resistance has been broken by addiction to drink and desperation, whose need for shelter and safety leave him no other option in order but to perform grotesqueries as a sideshow attraction to survive; high on his own sense of superiority from the “yokels” he so easily charms into belief, Stan feels only disgust for a character with such a lack of self-control or self-possession–– a character who’s lost the balance between his grift, an illusion, and his life’s reality. There are no tricks with a geek, just the drives that control every living thing, man or beast. As the novel windingly follows this would-be powerbroker through decades of ups and downs, from the dusty revival tent, to the hallowed halls of America’s most powerful, to the grimy boxcars he tried so desperately to escape in the first place–– and finally back to the carnival where he becomes the thing he despises most–– the geek is largely a marginal figure. Stanton’s self-involvement prevents him from seeing any kinship with this fleeting character whose raw need and reliance on others is so disgusting to him.

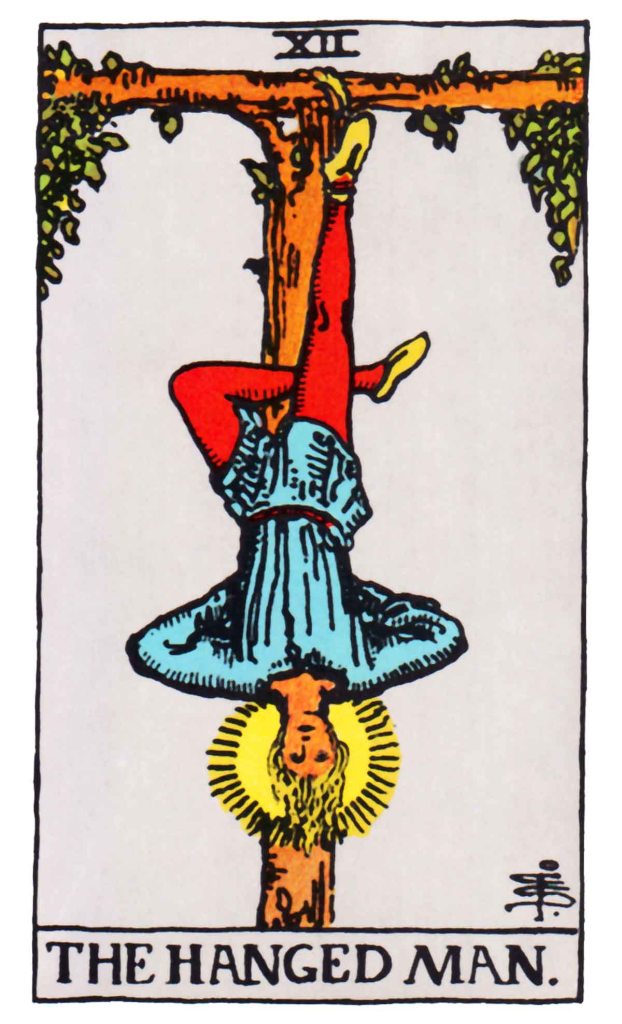

Stanton’s journey is demarcated by the Major Arcana of the Tarot, a symbolic system he tries diligently to disbelieve as just another con for the rubes he and his fellow carney’s fleece for their daily bread. The Hanged Man in particular dogs Stanton, turning up at every new phase of his life. This card and its relationship to the geek as well as the novel’s exploration of psychoanalysis and the supernatural, lie at the heart of the story. According to Morbid Anatomy’s Laetitia Ante Delictum, an intuitive counselor, tarot expert, and author of Tarot and Divination Cards: A Visual Archive, The Hanged Man card, which depicts “a criminal who has been

punished for having betrayed his peers… speaks about being held to the divine, powerless.” The intervention Nightmare Alley makes with Stanton’s ultimately futile attempts to game fate is the suggestion that, whether that fate is divine or a product of his psychology is irrelevant: the end is the same.

Stanton’s downfall comes at the hands of a psychoanalyst named Dr. Lilith Ritter, but was evidently destined from the beginning of the story. The doctor’s name in and of itself (Lilith, the “demonic” first wife of Adam in the Bible, who was expelled from Eden for her disobedience to her husband) demonstrates Grisham’s ambivalence towards science as a universal truth distinct from divinity or superstition. She is an unreliable if strong femme fatale, using her sexuality as a tool to cut in on Stanton’s grift and later swindle him of all the money he worked so diligently to steal. She uses the information she’s gleaned about his childhood (an Oedipal desire for his

mother and hatred for his father, burgeoning alcoholism, etc.) to gaslight him. Their relationship was never sexual, she will tell the police, rather he has delusions stemming from a traumatic childhood and has concocted a fantasy based on the maternal and sexual authority he has attributed to her. The fact that the psychoanalyst is a better con-artist than Stanton himself does not suggest that science triumphs over superstition, however. Merely, this conflation between the two indicates that whether Stanton is a product of the tangible realities defined by science or the unknowable will of God, he is, like the Hanged Man, powerless in the face of the force that controls us all, however any of us choose to define it: fate. Ante Delictum, suggests the link between psychology and superstitious games of fate like the tarot explored in Nightmare Alley has historical precedence:

“Games and psychology have always been intertwined, since playing offers a simulation

that allows us to either win or lose and live heightened emotions, outside of our everyday

life, in a different framework. Jungian psychoanalyst Maria Von Franz wrote… [that] we

are drawn to interpret chaos and find potent messages in randomness. Games, such as

dice and of course cards, were historically hijacked spontaneously by people to read

fortunes and answer questions of their everyday life… [tarot and psychology] both aim to

reveal hidden parts of ourselves, allow us to reinstigate an inner dialogue and mend the

psyche.”

For the characters of Nightmare Alley, this is undoubtedly true. Stanton Carlisle is incapable of reconciling his intellect with his emotions, agonized by this disjuncture whether it’s represented either by the Hanged Man or by his therapist-cum-torturess. Though he believes himself a cynic, this stance is clearly forced. He works to scorn the cards as well as therapy, though both

nevertheless hold sway over his imagination; Lilith, as well as mentors at the carnival like Pete, read him like an open book, drawing him in and playing on his fears. It’s notable that other characters are able to interpret their lives through one or the other of these methods–– in addition to the novel’s third, intermediary science/religion, Spiritualism, a perfect synthesis of the two warring world views which defined the latter part of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th–– and thus navigate their lives with greater ease than Gresham’s tortured protagonist. These characters are no less slaves to their fate than Stanton, however their acceptance of whatever larger forces of nature govern their lives allows them to accept the world as they find it–– and more importantly, their use of symbols to clarify and interpret their own experiences helps them heal. Stanton’s refusal to read himself is eventually his downfall. Whether or not the story’s demons are real, their existence in the mind is just as powerful.

Stanton Carlisle is blind. His tricks render him incapable of reconciling the parts of himself that put him in agony through either method. He scorns the cards as well as therapy, though both hold sway over his imagination.

Tipping The Scales: The Films

The two film adaptations of Nightmare Alley, the first in 1947 and the second in 2021, take contrasting approaches to the film’s themes. In the first, a stark, slimmed-down Hays Code era work of hardboiled B-movie sensationalism mixed with religious parable helmed by prolific British director Edmund Goulding, the story’s rough edges–– among other things, ample Oedipal sexuality and references to abortion–– are sanded down. Beautifully shot on a fully operational carnival built by the studio for the project, the story’s grim tone is replicated, but its message is altered by a thick layer of Christian proselytizing that upsets the novel’s careful balancing act and tears a hole into its meaning. Here, religion is presented as the “correct” symbolic register, eschewing the novel’s bleak ending in favor of a Deus Ex Machina wherein Christ and the love of a good woman can change a man’s fate. After becoming the geek, Stanton (an against-type Tyrone Power) is discovered by Molly (a sweet Colleen Gray), who assures him rather blandly that everything will be alright. In this version, Lilith’s role is downplayed while scenes of religious hucksterism on Stanton’s part are foregrounded, from a mocking con on a devout sheriff to the climactic swindle of a guilty millionaire–– presented cynically in the book but earnestly here.

These changes evince the fact that even in a period known for its dark, morally complexgenre filmmaking, Gresham’s source material was too bleak to pass muster. The Hays code’s edict against mocking religion clearly shaped this story, offering comfort that wasn’t otherwise available. Still, this pat ending can’t avoid the parallelisms between this newly redeemed couple and the one whose lives Stanton originally destroyed: Zeena and Pete, another alcoholic man associated with The Hanged Man. Molly may have him in hand now, but there are always more Stantons in the world–– as the barker tells the down-and-out Stanton the Geek, “mentalists are a

dime a dozen these days.” Within this crack in the Hays Code facade of Goulding’s film, as well as the lush, surreal shooting of the actual carnival set used for the production, Gresham’s occult- infused tale of bereaved and broken bodies and minds is still visible.

Guillermo Del Toro’s film adaptation of Nightmare Alley (2021) Searchlight Pictures

Guillermo Del Toro’s 2021 adaptation, meanwhile, a sumptuous big budget epic, adheres more closely to the novel structurally, but casts Stanton himself (here played by Bradley Cooper) as a sympathetic character by actively aligning him time and again with the geek, a figure he views here with conscious empathy and compassion that others don’t proffer. This change makes Del Toro’s film a tragedy, changing its fundamental message. In the novel, Stanton’s hubris, arrogance, and cruelty are the very characteristics which define the nature of his fate. In this film, though, his victimhood becomes less cosmic, less karmic, ultimately diluting the poignancy of the original parable’s blend of old school religion, populist superstition, and elite science. Here, though, previously censored details are re-inserted, making the story’s quasi-gothic and occult underpinnings more obvious. Del Toro highlights the arcane symbolism of Gresham’s work throughout, nodding to Hitchcock’s Spellbound with an often hallucinatory style and dark color palette.

Both films do however make a significant change to the novel’s ending: when Stanton finds himself down-and-out at the carnival once more, facing nothing but the prospect of a spiral into addiction and a lonely death, the barker makes him the offer his former boss at the show describes giving every new geek he hires. This verbatim recitation of familiar lines delivered by a new character are the only rejoinder the book offers; Stanton is left voiceless, leaving the reader to infer his choice and feel the horror of his fate. This choice speaks to the novel’s brilliant play with questions of psychology and fate: His answer is ultimately beyond the point because the hand he was dealt (so to speak) remains the same, sealed by his fundamental lack of empathy for others or real grasp of humanity’s emotional complexity. He is left without enlightenment in the novel because, as Stanton himself believes, a geek is not a man but a beast.

Though both film adaptations differ in their interpretations of the novel’s ultimate themes, they both provide him with a final line in the face of his new life as a geek: “I was born for it.” Regardless of their endings, regardless of whether one chooses to view his character through the lens of science or the lens of faith, this assertion made through laughter and tears is the only time Stanton Carlile is right. Underneath it all, it’s this inexorable pull of fate, by any name, that lends this story an unmistakable occult aura.

Payton McCarty-Simas is a writer based in New York City. They hold a Masters in film and media studies from Columbia University, where she focused her research on horror film, psychedelia, and the occult in particular. Payton’s writing has been featured in The Brooklyn Rail, Horror Studies, and others. She is also the author of two books, One Step Short of Crazy: National Treasure and the Landscape of American Conspiracy Culture, and All of Them Witches: Fear, Feminism, and the American Witch Film (to be released fall 2025). She lives with her partner and their cat, Shirley Jackson.

Leave a comment