by Larissa Zageris

The pilot for ‘90s hit sci-fi procedural series The X Files presented the horrors of alien abduction, and women not being taken seriously.

Strange lights in dark woods, aliens mind-controlling teen abductees, a town keeping deadly secrets, mysteriously missing moments in time, and a woman most men only see as a means to their own ends…Well. Simple alien horrors are classics for a reason, and The X Files pilot is a classic of simple, scary, small-screen cinema.

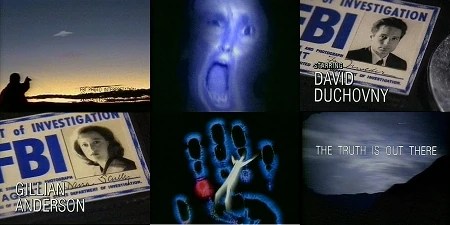

The groundbreaking sci-fi TV procedural seared supernatural horror into the pop cultural collective unconscious, putting emotionally evocative moments and indelible screen images to Gen X government suspicion and kooky outsider alien conspiracy theories faster than you can say “Vecna’s your uncle.” The X Files pilot alone, written by show creator Chris Carter, is responsible for alien horror scenes so iconic, that they were parodied by an episode of The Simpsons.

Even if you’ve never seen the pilot or the parody episode, (called, shockingly, The Springfield Files) chances are both have informed your deeply-held sense that an alien invasion will start quietly in the woods, with the teens. The grownups will ignore these teens, or overprotect them. Either way, the result will be the same: the teens will lose, the aliens will win, the government will cover it up, and a pair of Special Agents with great chemistry and ill-fitting suits will disagree about the reasons why.

But the spooky conspiracy meat and potatoes of the series and pilot aside, there is a basic, lasting, double- to triple-threat alien horror present in The X Files pilot episode. This uneasy feeling of being out of place and time sticks in the mind like sunflower seeds stick in the teeth. A state of alien cruelty, anguish, alienation and aloneness slithers through the pilot, only momentarily broken by the teamwork of an otherwise overlooked dynamic duo and the horrors they confront every week.

That feeling of alienation is extra-special when placed in a cool cucumber, and there is no initially cooler cucumber than Special Agent Dana Scully. Played with an almost serene sense of scientific superiority and briefly wild-hearted wonder by Gillian Anderson, Scully is a brilliant forensic pathologist and medical doctor. Still, in The X Files pilot, she might as well be an alien. Young, fresh-faced, and female – despite her oversized suit’s best efforts to make her male co-workers forget that fact for a moment – Scully calls to mind Clarice Starling in the 1991 film adaptation of The Silence of the Lambs.

Scully is smart, dry, and so ready for a moment to prove herself in the big, bad FBI. She thinks she finally has it, having been pulled up by top brass for some top-secret confab ticking off her many talents. But the look of dread on Scully’s face when she realizes the good ol’ boys only want her for – allow the phrase for emphasis – bitch work.

Of course, Scully’s abilities are finally being recognized by her overwhelmingly male superiors, only to deal with another male coworker who has gone off the rails with his extracurricular work. It’s down to Scully to scupper Special Agent Fox Mulder’s (David Duchovny) pet X Files investigations. He’s a crackpot, and she’s who the Bureau can spare to document such, and patch him up. The assignment is not so much a stepping stone for Scully or a recognition of her ambition or intelligence, but rather, a deployment of a pawn in a game of 4D chess.

It’s a tale as old as time. The aliens are terrorizing the teens, and the men are underestimating a smart, capable, awkwardly-suited woman.

“Am I to understand that you want me to debunk the X Files project, sir?” Scully asks her superior, Section Chief Scott Blevins (Charles Cioffi) in the pilot, mere moments after we’ve seen a teenager snatched from the earthly plane by a maliciously white beam of light in a densely wooded area of the Pacific Northwest. You’ve never heard the word “debunk” until you’ve heard Anderson act it in this context. Forget facehuggers, forget the creatures from The Thing, and instead consider the simple horror of a woman made to feel unwelcome and inadequate on this earth, when she knows her worth.

In the pilot, however so much as ‘90s TV episode can, a real alienation is explored. In looks and uncomfortable shifts of body weight, in mouths opening to speak, thinking better of it and shutting again, in secrets being told in lost time, urgent glances, and blasts of light.

“It’s happening again, isn’t it?” asks a put-upon coroner of his police partner in The X Files pilot, mere moments after a teenaged woman dies because of alien abductors, and moments before Scully is tasked with proving why. While the question implies that a scampy, small-town alien abduction has happened again, it echoes the misogynist crimes against Scully and her expertise back at the FBI.

But that great spooky and floofy-haired goof, Fox Mulder, sees Scully as an equal, rather than an errand girl. His genuine respect and concern for Scully cuts through the pilot’s loosey-goosey mystery elements, and even its outrageously out-of-character moments of forced physical intimacy when Scully shows him her naked back, fearful of having been kidnapped by aliens. In the pilot, Scully is safe with Mulder, even when Scully and Mulder aren’t safe at all.

The actual aliens in the pilot are plucking teens from earth, marking them, and destroying them after tests. But Mulder and Scully become their own brand of alien activity while out investigating it. Together, they bridge the lonely gap the rest of the world creates around them (Scully), or that they put between themselves and others (Mulder), and that a chain of pained families and craven, conspiratorial government officials put between their town’s teens and safety.

The cool and barely-considered disinterest in Scully as a human by her superiors is tantamount to the pilot’s treatment of the town’s treatment of teenagers kidnapped by aliens. Some basic respect and protections may exist for both Scully and the teens getting ganked by alien invaders, but generally speaking, both these beings are treated like grist for the mill.

Scully may not see actual aliens, but she can see what everyone else ignores. Even when Mulder poses the impossible idea to Scully, that the teens that keep dying in this town are doing so because a paralyzed member of their group is dragging them to the woods at alien mind-control’s behest, Scully squints to find truth in the lie. She finds it, by sneaking a peek at the supposedly bed-bound suspected teen’s feet in the hospital. The boy’s feet are dirty from running, and Scully sets her mind to work alongside the only man we’ve met in the pilot who actually kicks her the ball, so so speak, instead of tells her exactly what she is to do with it on his behalf.

Scully’s strength as a paranormal investigator doesn’t come from her belief in the unbelievable, but rather, from her meticulously rational investigation of crimes against the innocent. While it may never occur to her, seems like there’s a deep reason for that. Meanwhile, Mulder has his reasons for putting faith and following into alien abduction, but unlike their superiors, he also puts both into Scully. But at episode’s end, when the heartbroken townsfolk’s shotguns are cocked and the menfolk are willing to continue telling lie upon lie to hide the truth, their guns are pointed at Mulder, rather than his female partner in crime, it’s easy to see that Scully is the only alien on the planet, long before her own eventual alien abduction.

Leave a comment