By Cullen Wade

Though it’s difficult to pinpoint the term’s first use, cinema lovers know that “the apartment trilogy” refers to three films by Roman Polanski—Repulsion (1965), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), and The Tenant (1976)—revered for their portrayals of paranoia, helplessness, and loss of agency amid the complexities of urban living, and for distorting physical space to mirror their characters’ mind states. Another filmmaker whose apartment trilogy deserves to be mentioned in the same breath is Tobe Hooper. With The Apartment Complex (1999), Toolbox Murders (2004), and Djinn (2013), Hooper explored many of the same themes as Polanski through a unique lens: his career-long obsession with the corrosion, and corrosiveness, of the family home. These underseen, late-career Hooper highlights are gifts to horror fans who want something Polanskian but are conflicted about watching films by an admitted sexual predator.

In 2016, Hooper told a French interviewer about “the kind of thing that calls to me, and […] interests me most of all, and that’s this ironic kind of insanity that pops out in almost everyone’s family […] things you’d see in some Fellini movies, and in Polanski films.” Since Hooper cites Polanski as an exemplar of what “interests [him] most of all,” it’s worth investigating what links the two directors. Not much has been written about the Polish auteur’s influence on Hooper, and I do not intend to write much here—Polanski neither needs nor, in my opinion, deserves more ink spilled about him. But a look at the cues Hooper took from the older apartment trilogy is a good starting point for our consideration of his own.

Rosemary’s Baby echoes loudest in Toolbox Murders and Djinn—the latter in the patriarchal expectations imposed on the heroine’s womb, the former in the slow unveiling of the building’s occult secrets. Both films recall Repulsion with visuals of physical space mirroring psychic space as their leading women’s paranoia mounts. The Apartment Complex and The Tenant are outliers in similar ways: both focus on single men rather than women or couples, and both lean into humor and Kafkaesque absurdity. All six films—the Polanski trio and the Hooper trio—address the unique challenges of people living on top of each other, within both space and time.

Unhealthy Homes

From a working-class rural Texas homestead hung out to dry by consolidated capital (The Texas Chain Saw Massacre), to the depersonalized suburbs and those who profit from them (Poltergeist), to a career-switcher trying to revitalize a funeral home gutted by civic mismanagement (Mortuary), Hooper’s filmography is full of family homes in constant flux. While many of his films deal with families who are isolated, either geographically or socially, the Apartment trilogy inverts that idea to explore the psychological effects of living in proximity to others.

In all three films, Hooper’s protagonists are displaced people arriving at apartments to start new lives. The Apartment Complex follows Stan, who has just moved from the Midwest to southern California for graduate studies in psychology. He accepts a manager job at a bizarre complex called Wonder View Apartments. After fishing the body of his predecessor Gary Glumley from the neglected swimming pool, Stan finds himself suspected of Glumley’s murder—an absurd notion, since he hadn’t yet arrived in California when the manager perished. In Toolbox Murders, a young couple named Nell and Steven move from New England to a historic but decrepit Hollywood apartment building called the Lusman Arms, where new renovations seem to have kickstarted a murder spree targeting the residents. Another young couple, Djinn’s protagonists Khalid and Salama, move from the U.S. back to their home country, the United Arab Emirates, to pick up the pieces after their baby’s death. Khalid’s employer arranges housing in a brand-new, nearly unoccupied desert highrise called Al-Hamra, where strange events and even stranger neighbors echo the couple’s unresolved trauma.

In their own ways, all three films interrogate the myth of the safe, steadfast family home. Through Stan’s narration in The Apartment Complex, we learn that the Wonder View is his first home away from his parents. He lived with them during undergrad to save money and subsequently lived in his car. Now, states away, mom and dad are mere unheard presences on the other end of the phone. Stan is reluctant to share about his bizarre predicament, lest he disappoint them. After being arrested, he contemplates using his “one phone call” to contact his mother but then has second thoughts. “What am I gonna say? ‘Hi ma, remember that dream you had for me […] where I graduate from college, get a job, get married, and have grandkids for you to play with? […] I may have to postpone it, for, say, twenty years to life!’” The scene highlights the discontinuity of familial bliss & the road bumps on the expected path through American life that are key to Hooper’s fictions. For another character, Morgan, the mere mention of family provokes madness. Morgan says that Stan, using psychology to try to calm him down, sounds like his mother. “I hated my mother!” he continues, and punches Stan in the face. After the complex’s residents come to Stan’s rescue, he begins to see them as a quirky surrogate family, but the relationship is complicated by the reveal that they fabricated the evidence used to free him. Their last gesture is to push him into the swimming pool—the site of the murder—reinforcing his place in the hierarchy.

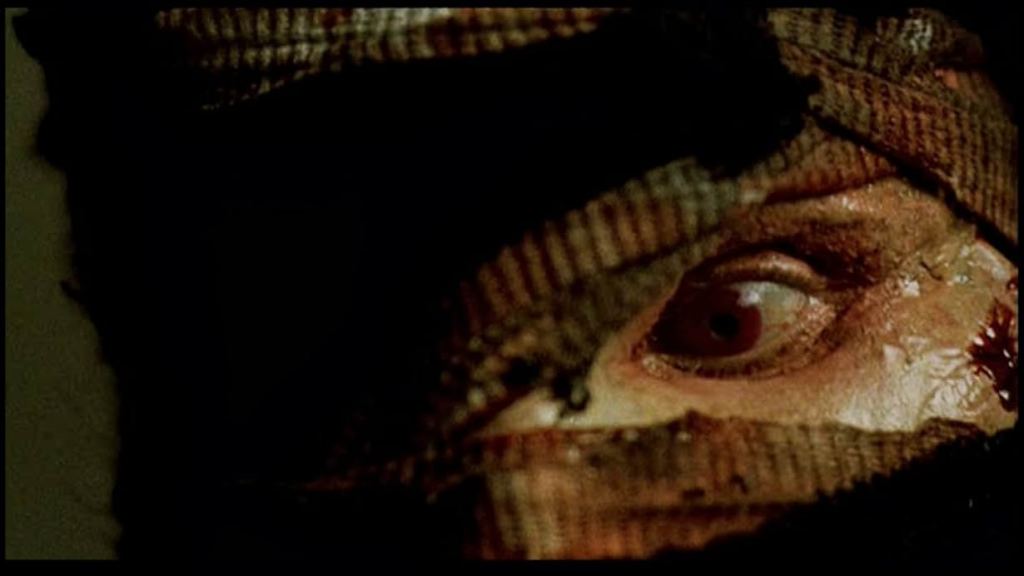

Similarly cut off from support structures are Toolbox Murders’s Nell and Steven Barrows, who just moved to Hollywood from Rhode Island after the death of Nell’s father. Upon learning of this, a neighbor says, “You lost the first man you ever loved,” emphasizing the primacy of the parental relationship and Nell’s unmoored feelings after its loss. Neither Nell nor Steven ever mentions a living relative. Unlike Stan—and despite the slumlord Byron’s insistence that it’s a “friendly building,” that they’ll “feel right at home” upon befriending the neighbors like the “nice family” down the hall—the Barrowses are not lucky enough to find chosen family in the Lusman. But there’s someone else who does. In an exaggerated echo of Nell’s disorientation after her father’s death, the film’s killer has also lost a parent. The aptly named “Coffin Baby” was assumed dead along with his mother, until he emerged “fighting his way out of his mother’s womb as she laid in her casket.” Coffin Baby’s twistedness, the film implies, comes from never having known the loving support of a family for so much as a moment. Instead, his nurturing parent is literally the building itself. The occult symbols woven into its architecture create a spell that has kept him alive, and his murder spree is a response to planned renovations that threaten to destroy the building’s power.

Like Nell and Steven, the couple at the center of Djinn are relocating after a family member’s death. But Salama and Khalid are not moving away from family, but rather closer to it. Salama’s mother, father, and sister live in the U.A.E. and meet the couple at the airport to drive them to their new home. Khalid, though, is an orphan much like Coffin Baby, born into supernatural circumstances and violently separated from his family of origin. His mother is a djinn, a mystical being from Qur’anic folklore, who conceived him with a human man in the fishing village that once occupied the land where Al-Hamra now stands. The film reveals that the death of Salama and Khalid’s baby was not accidental—Salama killed it upon realizing she had given birth to something not wholly human. Khalid’s djinn mother, Umm Al Duwais, lures the couple back to their homeland so Salama can have another baby under closer scrutiny. (And you thought your mother-in-law was a nightmare.) After they arrive, the first thing the djinn does is murder Salama’s family, removing her support system and making her dependent on Khalid. Like a heroine from Polanski’s Apartment trilogy, pinned down by patriarchy and facing the prospect of bearing an inhuman child (I don’t mean Rosemary, I mean Terry Gionoffrio), things do not end well for her.

Hooper’s three films depict characters in progressive stages of adulthood: striking out on their own, coping with loss, and starting a family. All three use techniques from the same toolbox to depict the “ironic […] insanity that pops out in almost everyone’s family.” In the visual language of these films, it’s not just the events that happen in the apartments that are uncanny, it’s the living spaces themselves.

Strange Spaces

The Apartment Complex, according to one character, is an “official architectural anomaly.” Stan is told its irregular swimming pool is “the only one of its shape in the western hemisphere,” and later a police investigator calls it the “deepest pool I’ve ever seen.” Hallways branch at odd angles, dimensions are contorted—nothing makes sense. The film highlights this crazy geometry by opening and closing with bird’s-eye views of the complex, using the visual metaphor of rats trapped in a maze. One character tells Stan that the Wonder View consists of “Twenty-one apartments, count ‘em. Not as easy as you think.” Indeed, when a package arrives addressed to apartment 17, Stan tries in vain to find it. The units on each side are there, but 17 eludes him. The missing apartment motif also shows up in Toolbox Murders, where Nell discovers that each floor is absent its apartment 4. With the help of an archivist at the Los Angeles Preservation Society, she figures out that the building’s design subtracts a small bit of square footage from each apartment, and the accumulated space creates an in-between area where Coffin Baby makes his home. “Our minds don’t work with these sort of spatial anomalies,” the archivist says. “There’s a whole townhouse inside your building.”

In Djinn, the Al-Hamra’s form is not as front-and-center as the Wonder View’s insane geometry or the Lusman’s “unique architectural designs,” but it is uncanny in its own way. Eerily empty and perpetually surrounded by fog, it soars from the desert floor to a dizzy height, seemingly the only building in the area. The elevator has a mind of its own, the security cameras show Salama things that are not there, and the interior’s polished trappings are luxurious but soulless. The couple’s apartment, at the end of a hall, is catty-corner rather than parallel to its neighbor—not as dramatic as the Wonder View’s cyclopean skew, but enough to tell us something is off. Like in Toolbox Murders, the reason for the building’s strangeness is a key to the antagonist’s motive: in reality, the Al-Hamra is still under construction. The tower that Salama sees is an illusion created by Umm Al Duwais to trap her into having another baby. The staff, neighbors and sumptuous rooms are all hallucinations; Salama and Khalid are imprisoned in a djinn’s magic bottle, invisible to outsiders who see the building as it really is: a work in progress, plastic sheeting, sawhorses and all.

Hooper’s films have always been undergirded by a strong sense of place. In the filmmaker’s world, geography is inextricable from history. The obvious example is Poltergeist’s suburb built atop a graveyard, but don’t forget about the accumulated layers of family madness at the Sawyer home, the Marsten house’s ages-old darkness, and the reptile-haunted hotels of Eaten Alive and Crocodile. Where the apartment trilogy is concerned, the theme shows up most clearly in Djinn, where the Al-Hamra is built on the site of the demolished fishing village where Khalid was born. In Toolbox Murders, the Lusman’s “bad juju” results from its builder’s deliberate attempt to create an architectural grimoire, but a bloodier history is hinted at in Byron’s offhand remark about Elizabeth Short (the famous “Black Dahlia” murder victim) having lived there. There is even a suggestion of past tragedy at the Wonder View: several residents recall the long string of interchangeable complex managers who have come and gone. As part of The Apartment Complex’s lab rodent motif, Stan notes that “rats respond to high population density with mass hysteria.” A twist ending reveals that Gary Glumley was not the body in the swimming pool; rather, he was the murderer. Glumley, who appears to have no family—at least none who are interested in claiming his belongings—became obsessed with the notion that one of the tenants wanted to kill him, so he struck first, drowned him in a waterbed, and assumed his identity. But the idea that close communal living can lead to madness is true, Hooper’s films suggest, when people share space not just physically, but temporally as well. Even if you don’t know the history of your living space, you can never be unaffected by what happened there.

At the risk of falling back on an overused term, Hooper’s apartment films live in liminal space. They depict characters at turning points—often between life and death. Consequently, the buildings are full of in-betweens: Coffin Baby’s lair concealed within the Lusman’s walls, a false Al-Hamra hiding inside the real one. Missing apartments mirror voids in the characters’ lives: Nell’s loss of her father, Stan’s loss of control over his fate, and understanding of the world around him. Even more absences lurk outside: we are told the Lusman sits in a bustling commercial area that we never get to see; the Al-Hamra is located at the seashore but the fog never lifts enough to reveal it. The only evidence of a Los Angeles outside of the Wonder View is a featureless room where Stan and his classmates observe lab rats and a brief detour to the interior of the police station. Each film is contained in its own little snowglobe, where the characters’ psyches warp to match the contours of their worlds.

Ironic Insanity

“Irony” is a notoriously tricky word to define, and Hooper did not elaborate on precisely what he meant by “ironic insanity.” Taking the apartment trilogy as a whole—Coffin Baby’s homicidal urges stemming from a lifelong lack of love, the hothouse paranoia that drove the unrooted Glumley to murder his tenant, Salama’s hallucinations caused by her inhuman mother-in-law and the unthinkable decision to kill her baby—we might conclude that the “insanity that pops out in almost everyone’s family” is the direct result of the Sisyphean human endeavor to create stable homes in an unstable world. There is a basic irony to the way these stories play out: the characters’ attempts to create order are what cause all the chaos. But as in many Hooper films—the Sawyers’ lair beneath an amusement park, the tunnel network where the Invaders from Mars make their stronghold—there is a deeper level. The truly ironic part is this: the insanity is not foreign, not an intrusion upon domestic wholesomeness. The madness, quite literally, comes with the territory.

Leave a comment