By Mo Moshaty

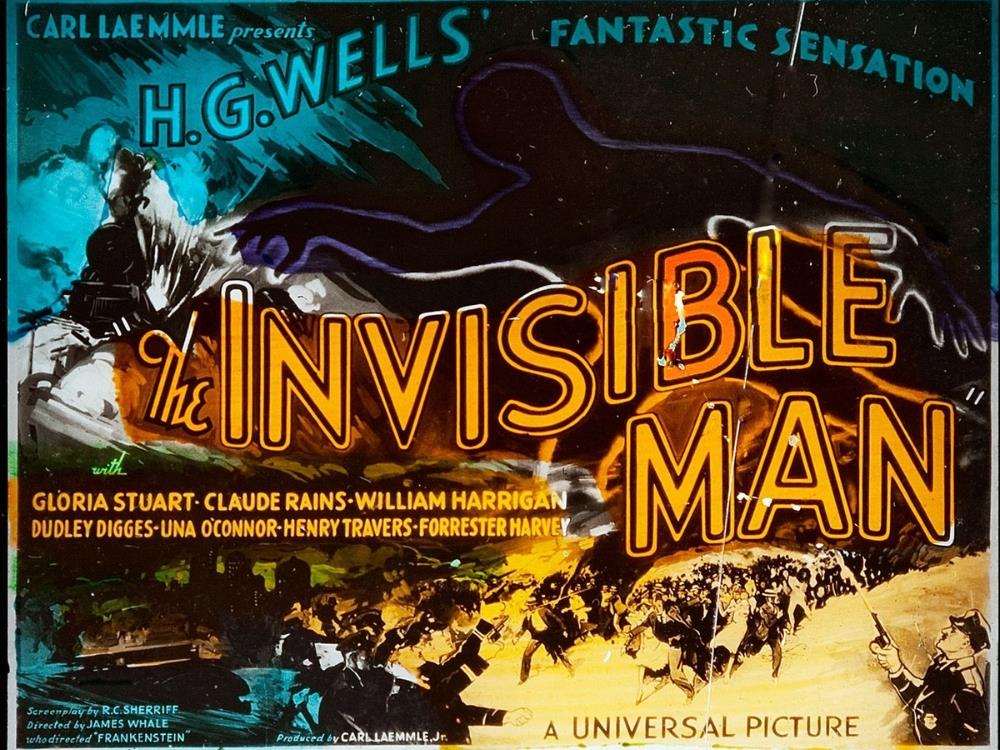

The Universal Monsters franchise left an indelible mark on cinematic history, and The Invisible Man (1933) stands out as one of its most psychologically complex entries. Based on H.G. Wells’ 1897 novella, the film introduced audiences to the terrifying allure and dangers of invisibility. This concept has not only shaped horror and science fiction, but has also sparked a legacy of stories that explore the darker sides of human nature.

If I was invisible

Then I could just watch you in your room

If I was invisible, I’d make you mine tonight

If hearts were unbreakable

Then I could just tell you where I stand

I would be the smartest man If I was invisible

Wait, I already am

No, these aren’t the twisted words of a serial killing stalker to a possible victim. These are the lyrics to the 2003 pop smash hit by American Idol contestant, Clay Aiken, where a meek, nebbish guy has the hots for a babe but just can’t seem to get her to look his way. Aiken laments that if only he was invisible, he’d have the power to ogle her unseen and perhaps make her “mine” – it’s giving heavy ghost sex vibes not to mention the skeevs. But what is it about the power of invisibility that makes us yearn for its mischievous possibilities? Well, for starters, it represents a desire to escape, to avoid unwanted attention, and in Aiken’s case, observe others without being noticed, taking the Peeping Tom act to the enth degree. There’s also that sweet, sweet freedom to do whatever you damn well like undetected.

In The Invisible Man (1933), Dr. Jack Griffin’s (Claude Rains) discovery of invisibility is nothing less than a double-edged sword. Immense and godly power, yes, but also mental and moral decay. Being free from literally any accountability, Griffin’s actions spiral into terror and extreme violence, and this descent into madness serves as a pre-code cautionary tale about the corrupting nature of unchecked power.

What would you do if you couldn’t be seen? A contestant on Australian Family Feud’s answer was, “let’s just say there’d be a lot of dead bodies, and no one would ever find out.” Insert groans and gasps from the audience and nervous laughter from the poor man’s wife.

Fear of the unknown has always been a driving force in Sci-Fi horror and for good reason. Its human nature to want to rise above our mental and physical prowess to something God-like and substantial and The Invisible Man story executes it perfectly. Griffin doesn’t just invoke invisibility; he manipulates the will of others through their inability to detect him. The power of acute mindfuckery works to Griffin’s advantage as it jacks his menace up to eleven as he terrorizes those around him. Whale’s use of fear highlights how invisibility is not just about physical absence but the psychological terror it imposes on its victims.

Claude Rains, The Invisible Man (1933), Universal Pictures & Oliver Jackson-Cohen, The Invisible Man (2020) Universal Pictures.

But the idea of invisibility has blossomed in our tech advancements of the last three decades. Incognito search histories, invisible WhatsApp status, no read receipts, anonymous trolling, anonymous online voyeurs, keyboard warriors, the list goes on, reminding us how far people will go when they feel unseen and untouchable.

Leigh Whannell’s The Invisible Man (2020) builds on this idea, reframing invisibility as a technological tool for emotional manipulatiom, gaslighting and punishment. Adrian Griffin’s (Oliver Jackson-Cohen) use of invisibility to stalk and torment Cecilia Kass (Elizabeth Moss) reflects how the fear of an invisible force can mirror real-world experiences of abuse.

Adrian Griffin’s a catch. Bruce Wayne money. Howard Stark brain. Captain America looks. He’s gonna be the prize bull at the Bachelor Auction fo sho! But his terrifying tactics to keep a clearly terrified girlfriend chained to his side is nothing short of disquieting. The relationship is highly controlling, and Cecelia is sequestered in their high-tech and very, very isolated prison-lite architectural marvel. Isolation is the first step in the social alienation tactics of an abuser. As a wealthy optics engineer, he leverages technology to create chaos in her life, he systematically breaks off her ability to communicate effectively with her support network of friends and family. Adrian exploits Cecelia’s knowledge of his intellect, making her question her own perceptions and reality. From the smallest gestures in his invisibility, he moves objects, turns lights on and off, taking Cecelia’s sanity to the brink. Gaslight much?

In the escalation that always happens, Adrian fakes his own death and sets up a legal trust for Cecilia, using the inheritance rules to control her decisions and keep her under his thumb. He torments her with everything he can think of: hacking into Cecilia’s email to send hostile messages to her sister Emily (Harriet Dyer), destroying her closest relationships, and he uses his invisibility suit to commit acts of violence; in the jaw-dropping restaurant scene, he murders Emily and frames her for the crime, turning society against her and leaving her powerless. The invisibility suit symbolizes his omnipresence, a constant reminder that she cannot escape his control.

The suit also allows Adrian to physically abuse Cecelia without anyone seeing, showcasing her vulnerability and highlighting how abusers hide their violence in plain sight. The final showdown had me whooping as Cecelia turns his own technology against him, reclaiming her agency. Whannell’s adaptation underlines how technology mirrors the hidden nature of abuse, critiques the power imbalances shaped by wealth and knowledge, and shows Cecilia’s resilience as she outwits Adrian and takes back control of her life.

The Invisibility Legacy extends far beyond Universal’s classic film, influencing generations of storytellers with its basis of psychological terror, manipulation and God-like energy. It seems from these adaptations, that the invisibility quotient is a predominantly a male fantasy of dominance and control with zero consequence, and the ethical dilemmas are still just as sticky and icky as they were in 1933. Griffin’s journey (1933 and 2020 respectively) raises the question about the morality of science when ethics are disregarded. Is unrestrained power ever a good thing? Cuz folks, invisibility power sure makes the rest of us sitting ducks for lack of privacy and consent.

We can’t touch on this issue without talking about Hollow Man (2000) as it delves into similar territory, presenting invisibility as a gateway to moral corruption. The character of Sebastian Caine (Kevin Bacon) begins as a sympathetic character, the victim of this invisibility experiment go awry, but as nature goes, Caine leans into his plight, exploring the dark corners of the mind and the endless and homicidal possibilities. It takes his fellow scientist ex-girlfriend, Dr. Linda McKay (Elizabeth Shue) to trap him and break the technological curse.

Even she-who-shall-not-be-named’s little magic boy uses an invisibility cloak to head into mischief or to save the day. No matter how seemingly insignificant and juvenile, the Legacy continues to be steeped in the themes of scientific hubris in the 20th century, to abuse, manipulation and anonymity in the 21st century. As technology continues to advance and societal anxieties shift, sink and worsen, the stories of invisibility will undoubtedly find new ways to unsettle and provoke, ensuring its eternal place in the hall of cinematic legacies.

Leave a comment