By Monica Ferrall

They’re heeeeere!

An invisible entity…

Hiding in the closet…

Ghosts on your television set. Bodies buried. Identities are hidden in monsters and heroes despite a culture that refuses to recognize them.

They’re here, they’re queer. Get used to it.

As the queer identity has a history of being demonized, silenced, and erased, horror stories became the perfect vehicle for its representation…always lurking under the surface unable to be named.

Queer folk have had their stake in horror as long as the genre has existed. While literary horror was shaped by masterminds Bram Stoker and Mary Shelley – who are both rumored to be under the LGBTQ+ umbrella – the horror film genre was spearheaded by the prolific and openly gay director, James Whale (Frankenstein (1931), The Invisible Man (1933), Bride of Frankenstein (1935), to name a few). James Whale and producing partner, David Lewis (also his life partner), directed these monster movies informed by their own queer experience, creating monsters that were rich in humanity though otherwise ostracized. Frankenstein, notably, represents the creation of life without procreation (read: heterosexual sex) and thus is an affront to God, himself. While this defiance of God reads as blasphemous to a god-fearing Christian, to someone oppressed by religion who has had the gall to stand up to it and reject it, this affront to God may feel a lot like power. And while directors like Whale used horror films for power: to bolster pride and sympathy in “The Other”; others saw only fear.

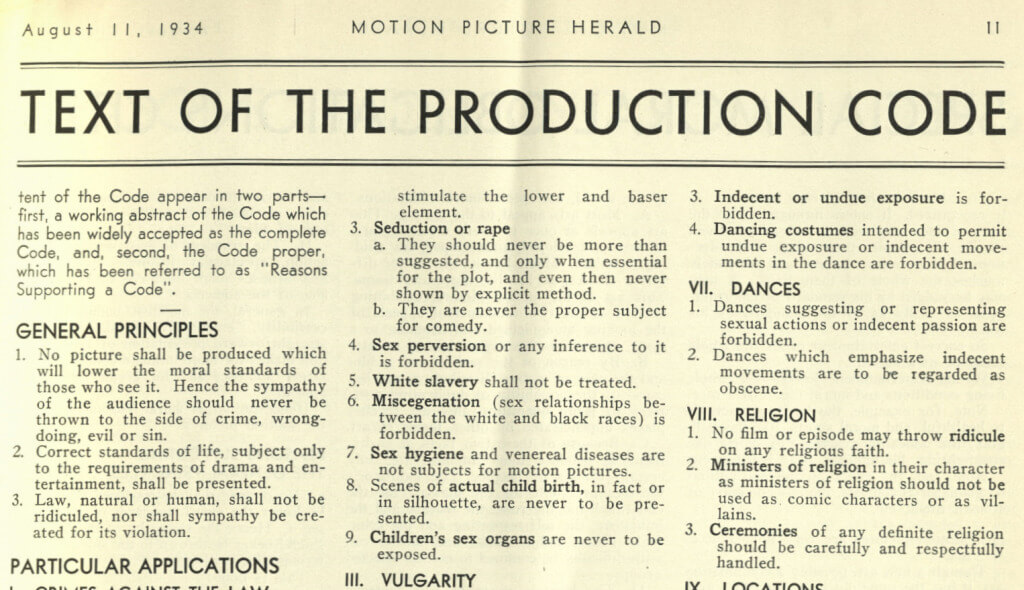

The Hays Code “Codes” Queerness

Hollywood, with its newfound power to reach screens across the country, became a new source of moral panic in 1934. Worried about the images and ideas Americans could now be exposed to, leaders looked to what every fragile country inevitably turns to – censorship – and the Hays Code was born.

While the Hays Code censored various “immoral activity” within film, its stance on anything opposing heteronormativity was quite specific and lasting. Accordingly, “no sexually perverse characters or storylines were permitted unless they met their demise by the film’s end or were explicitly villainous.” This put queer writers and directors in a bind. Not only did this demand future queer characters become invisible, but it set the framework for each queer discovery to end in vanquishment. From 1934-1968, in order for an LGBTQ+ character to grace the screen: they must be killed off (i.e. rarely the protagonist), not ‘actually’ be gay by the end of the film (i.e. under mind control of vampires), or explicitly villainous. While many of the films of these times abided by these guidelines, giving us two of the most problematic tropes for queer folk in the genre, many of them relied on what we now call “coded” queerness, subtle cues that some people would pick up on, but would fly over most of the audience – and more importantly, bypass the censors.

This coded queerness has become so embedded in the culture of queer identity, that it’s one of the more ubiquitous tropes: a character denying or hiding their queerness behind a canonical partner; characters affirmed in their identity but only in hints; characters alluding just enough those who might accept them to recognize their queerness, but not enough for the heteronormative world to condemn them. All this mirrors the way queer folks have lived for the past century. “Coded” queerness is a microcosm of queer survival. The queer experience is that of hiding in plain sight and that of scouring for clues — first for any hint that we may not be the only one who feels so deviated from the norm, and then in the search for a potential partner, friend — anyone with whom to share the secret. As Viet Dinh surmises in “Notes on Sleepaway Camp”, an essay in It Came From the Closet, “If I looked at the row behind me on the bleachers, I could see up another boy’s shorts, during basketball practice, a jump shot could mean a shirt riding up…I learned how to stay silent, how to cover my mouth with both hands so that nothing could escape. Not a whimper, not a sigh…I would stay safe.”

The world of horror requires strict boundaries, particularly in gender and morality, because horror upsets the status quo. Without strict roles, disruption is meaningless. The duality of horror and the complicated relationship queer and other marginalized folks have with the genre is this same essence – a character must be Othered before they can be redeemed, gender roles must be strict before they’re broken. This essay will analyze these gender roles and queer-coding as societal constructs. While gender identity and sexual identity are not linked, culture’s insistence on linking the two speaks volumes about what gender roles represent and what the fear of an identity outside them means for the patriarchy.

This restoration of order mandated by the Hays Code creates a world where homosexuality is either a phase or a ticket to the grave, burying gays both literally and figuratively. Horror movies and pulp novels became an apt place to explore outside gender norms, knowing that violence would always restore heteronormativity by the end. In these stories, queers were buried underneath the text, living their truth only in subtext, but they were likewise killed off to restore the ‘innocence’ of the protagonist. As these stories evolved to tell the queer journey, they continued to tell it in coded metaphors. The monster becomes the repressed sexuality that the hero must vanquish or accept. And because this experience was so fraught with trauma in an already homophobic world, as coming out became scarier, the monster did, too. But because we are still living in the land of invisibility, the land of metaphor, the story is always one of life and death. Which is perhaps why the supernatural film persists with queercodedness…in the land of the supernatural there is little separation between life and death and neither is permanent. The Hays Code required writers to “bury their gays”, and what better place to bury bodies than horror, where they have the power to rise from the grave?

The legacy of the Hays Code will take two essays to fully unpack: the first, focused on the invisible queer and the supernatural film, and the second, focused on the trope of the villainous queer and the development of the slasher film.

When we look at the Hays Code, we are not merely looking at a time of past censorship, but at the seeds of its impressionable beginnings. Film was censored so immediately following its inception, the censorship became woven into the fabric of it. When we look at the tropes and culture set up by the Hays Code, we look at the incipient roots that shape the state of film today. To fully understand these tropes, we must acknowledge the harm but also the complexity – the truth that hides behind them.

The Invisible Gay Becomes Visible

The Hays Code would end in 1968 and only 13 short years later, a moral panic would once again rear its ugly head — this time revolving around the HIV/AIDS epidemic. While this moral panic wouldn’t incite censorship, it would influence both how gay men, specifically, were portrayed in the media, as well as the lived experience these portrayals would imitate. The horrors of the epidemic, ostracization, and death would play out on screen, in both text and subtext. The gays that were formerly buried because of the code were now buried to reflect the reality of life. These films that metaphorically kill the queer, as a representation of repression, often literally kill them as well. In Witchboard, for example, which we’ll discuss at length when it comes to the possession elements, Jim suffers the loss of the man he’s closest to expressing queerness to before his own heteronormativity is restored.

And, due to the focus of this moral panic on gay men specifically, the lesbian, yet again, would remain invisible. More particularly these films would solidify archetypes that the supernatural/possession film would specifically mimic: that for males, queerness is an action they perform, while for women queerness is something that happens to them. Men fight battles with external forces to restore their heteronormativity; for a woman, it is restored with only a man’s kiss – as if lesbianism is a curse from an old witch that renders the woman helpless until rescued.

The monster as queer repression is best illustrated in A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge (1985), which also acts as a male possession film. Jesse’s haunting starts, notably, as he struggles to court girl-next-door, Lisa, and swiftly turns into a full-blown possession. Jesse’s failures in masculinity provide gay subtext, bordering on text, though the fact that Jesse takes the traditional female role of “Final Girl” exacerbates it. The penetrating nature of the supernatural codes Jesse queer as well. The way he interacts with the unseen (this is one of the few NOES films where he’s the only one who dreams about Freddy) puts him on the female side of the binary. Freddy Krueger literally fights Jesse from the inside, mimicking the female internal battle of the possession film. Furthermore, Jesse’s life (and gender identity) are restored by a kiss from a girl. As soon as Lisa codes him heteronormative, Jesse is freed from Freddy’s possession.

The actor playing the “Final Boy”, Mark Patton, himself was a young gay actor hoping to break into Hollywood while keeping his sexual orientation private. Upon the film’s release, however, the queer narrative was so noticeable, that his agent supposedly called Patton to tell him his career “would be over if he couldn’t play straight”. This reaction, I would argue, has far more to do with Patton’s character acting as both a “Final Girl” and a “Possessed/Monstrous Female” than it does his acting.

The other notable “Final Boy” of horror would be Ash from the Evil Dead franchise, who maintains his masculinity primarily through camp, but also because the demons he fights are of the external variety, and through fighting, he’s able to rescue others.

Lesbians in Spirit

The ‘coded’ or ‘invisible queer’ has lived on, hiding within the ethereal world of the Supernatural. The supernatural exists between the binary of living and dead, impossible and tangible, religion and science, seen and unseen. The supernatural story deconstructs all of these binaries to transport the audience into a fantastical world, and then neatly puts them back together to restore order. The supernatural world has always existed outside of the gender binary, as well, within the ethereal malleability of body and spirit – the prime place to explore the dissonance between reality and presentation – and there’s a strong historical reason for that.

While interaction with the ‘spirit world’ has roots in various cultures since the dawn of time, the history of Spiritualism in America has distinct female origins. The Fox Sisters, the inventors of the séance and subsequent popularizers of the Spiritualism movement started it as a prank on their nervous mother. The sisters created a hoax of knocks through the walls and attributed it to ghastly communication. The idea of contacting the spiritual realm caught wind, not only because it allowed folks a connection with passed loved ones, but because it created a platform for the female voice. One of the Fox Sisters’ favorite spirits to contact was “Benjamin Franklin”, who miraculously declared from beyond the grave an agenda more progressive than when he was alive. This not only had the power to advocate women’s suffrage, but it also granted a freedom to female mediums that weren’t otherwise allowed – the ability to present as another gender. Séances rose during a time of stifling sexual repression with little opportunity for polite society to mingle in impolite ways. The allure was in the spectacle, more so than actual contact of the dead. Folks enjoyed holding hands in a darkened room with the possibility that a spirit may possess them at any time, if just for the evening. Mediums, who may otherwise be dignified ladies, might be possessed by a lascivious sailor. Her voice might deepen, she might strike an unladylike posture and drink an unladylike amount, and… she might just kiss the other ladies. The kissing and the touching, in particular between women and ‘ghosts’ was an integral part of the whole séance experience.

When we see women or femme folk in roles that communicate with the spirit world, this is partially because it is seen as a more emotional sphere than science (science and logic are for “men”; metaphysics and emotion are for “women”), partially because women’s internal (“invisible”) reproductive organs restrict their power to the internal realm and partially because it was historically a way for women to gain a voice. Men, in early patriarchal days, did not need elaborate schemes to be listened to.

The spirit world would continue to break the gender binary along with the living/dead binary in on-screen explorations. It would also continue to have a distinct female influence, even if their queerness was still invisible.

The Haunting (1963), based on Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, follows Dr. Markaway as he hires two women to help him study the paranormal phenomena within the house. Dr. Markaway deliberately picks two women for his fringe science experiment, perhaps knowing he’ll have their buy-in, whereas the only other man (the house’s heir) remains a skeptic. Theodora (“Theo”) is a practicing psychic and Nell had paranormal experiences as a child. The supernatural has distinct queer undertones in this film as the woman better-versed in paranormal activity is also more aware of her sexuality. The two women are both mediums to an extent, though they could not be more different – even wearing opposing colors in each scene. After caring for her invalid mother up until her death, Nell is unmarried and grieving. Theo is also unmarried, though because she loves someone she cannot marry (read: a woman). While they both have psychic tendencies, Theo’s confidence opposes Nell’s uncertainty in her psychic ability, emotional control, and in her sexual orientation. Nell is the passive receptor of ghost phenomena, consequently completely out of control of her paranormal experiences and also completely out of control of her emotions. She spends most of the film wailing and flailing, etc. Theo, on the other hand, is in control of her power. She is poised, reserved, and even while she’s scared she does not make a fuss. She’s aware of her ability, whereas when Nell is faced with it, she runs (literally out of the house).

While the supernatural genre honors the history of women’s expertise of the world beyond the veil, it also allows the female the freedom to break from the “girl box” in the possession film. The possession film distorts the boundary of “femininity” to create what Carol J. Clover in Men, Women, and Chainsaws terms the “monstrous female”. As explored in Jennifer’s Body (2009), while possession films contain a compelling metaphor for puberty, they also explore the identity of the queer woman. And while the possessed female feels like the main character, the real protagonist is the man who saves her. This trope has adjusted away from the male savior angle, but it has also opened up to be less female-centric, as we’ll explore in the Insidious franchise.

Restoring Heteronormativity: The Battle Against the Supernatural

The Exorcist (1973) is a shining example of a man overcoming his queerness in order to save a young girl from her own. As with the invisible lesbian, Reagan passively becomes evil as a possession takes hold of her young body. She rejects religion, makes obscene sexual references and her body physically rots. Reagan is everything society fears from a young girl: in charge of her ideology and sexuality without shame, without her feminine beauty, and – no longer passive. While Possessed Reagan is essentially a demon, she is also every little girl who wants to ditch her girlish long hair for a less feminine haircut. Raegan’s mother panics at her loss of perceived femininity and innocence, as well as her bodily autonomy. And in the context of reflecting a patriarchal culture back to us, panicking about female bodily autonomy is almost too on the nose. The fact that the possession film allows religion to factor significantly in controlling and “rescuing” this young girl’s body, only primes it more for pairing the gender binary with the good/evil binary.

Furthermore in these films, the absent (or feminized) male, i.e. the lack of a ‘strong male influence’, forces the female towards monstrosity. As exhibited in The Exorcist, Reagan’s possession is more or less a result of her absent father, and her restoration to femininity depends on Father Karras maintaining his own masculinity. When women are incapable of rescuing themselves, they rely on the chauvinistic masculinity of men, and vice versa, for men to retain their masculine power, the female must be passive and helpless.

What is subtle in the film and obvious in the book, is that Father Damian Karras is actively repressing his homosexuality, believing his mother’s death to be God’s consequence for his temptations. Where the book can pack nuance and explore more deeply the themes of religious doubt and flexibility of gender norms, the film cements itself as a classic by focusing on restoring order. In a fatal self-sacrifice, Father Karras begs the demon to possess him and throws himself out of a window. This climax cleanly delivers the buried gay and the restored heteronormative order.

Witchboard (1985) also features a young woman possessed, though she’s saved by her boyfriend instead of a priest. Linda’s male influence isn’t absent, but emasculated; her boyfriend struggles to provide for her economically and suffers vices.

As Linda becomes more and more monstracized – the first clue to her possession is profanity, followed by a deeper voice and temper, until it becomes all too clear that ‘Linda’ doesn’t live there anymore – her boyfriend, Jim, and her ex-boyfriend, Brandon, team up to save her. These boys have a history and a tension, one chalked up to jealousy over Linda, though the film reveals a particular ambiguity about their past relationship. While they used to be like “brothers”, Jim has abandoned Brandon to seriously pursue a heterosexual relationship. Though neither says anything explicit, Brandon alludes that he’s bothered by the relationship though not because he’s jealous of Linda. These boys’ past must be confronted before Jim can begin to restore his masculinity, and Brandon must die before Jim can ultimately re-masculate himself and save Linda. Even as Jim breaks down with emotion —- he’s allowed to mourn Brandon’s death because he’s about to do the most heterosexual thing of all — rescue a woman and marry her. The tears represent one last purge of his homosexual identity.

Both Witchboard and The Exorcist seem to insist on an inevitability of non-heteronormative thoughts – as if the battle against these thoughts is universal and only the weak men fail. Between the queercodedness (or overt queerness), there’s an underlying current – ‘God tests us all with gay impulses and we must resist’. The adamance that homosexuality must be fought or resisted implies the ability to fight and resist it in the first place…as if those who are the most adamant are those who suppress their orientation the most.

This struggle of denying one’s identity continues to be coded even in recent films. Insidious (2010) presents the monstrous female in a completely different way, one that speaks to the malleability of gender and the spirit realm’s existence outside the binary. Femininity is monstracized within the film, though not through the main characters. Instead, Insidious, like its predecessor The Shining (1980), tells the ‘male’ possession story. Instead of a prepubescent girl in the throes of Satan, they explore the relationship between a man and his son and the generational trauma surrounding it. It’s interesting that in a genre traditionally dominated by aspects of the female, the male supernatural story pertains to fatherhood. This is a key area where the gender roles are reversed: Becoming a mother is an external battle while becoming a father is an internal one.

Insidious (2010), specifically deals with the horror of parent’s helplessness in the face of childhood illness as Josh Lambert’s son, Dalton, slips into a mysterious coma. Though Josh struggles throughout the film to act as an adequate father and husband, his biggest parental fears will manifest in the truth about Dalton’s coma. As the movie progresses, we learn that the coma has no medical explanation, but a metaphysical one. Dalton is capable of advanced astral projection, a skill he inherited from his father (an apt metaphor for inherited familial trauma), and has gotten himself stuck in The Further. To drive the metaphor home, The Further, though more so in the original script than the film itself, is occupied with distorted images of parenthood and consequently femininity. The demon that holds Dalton, hostage, has lipstick smeared across his face (though it plays as “fire on his face” in the film) and a protruding pregnant belly. The film genders the demon unmistakably male while presenting a distorted female image. He is a monstrification of motherhood as seen through fatherhood. In the context of Dalton inheriting The Further from his father, these demons represent everything Josh fears to pass on to his son. The distorted female image projected on a male demon hints at the fear of gender variance and repressed homosexuality as the franchise goes on to explore Josh’s own repressed demons which affect his marriage and ability to lead a family. And of course, in Insidious Part Two’s exploration of a serial killer forced to live as a female as a child, the theme of parental pressure and gender roles is all too obvious.

The Supernatural film allows us to break the gender binary, if only for a moment. As much as these films reliably end with a religious savior and heteronormativity restored — and as short as the time is that gender roles are broken, it feels pretty damn good.

Leave a comment