By Payton McCarty-Simas

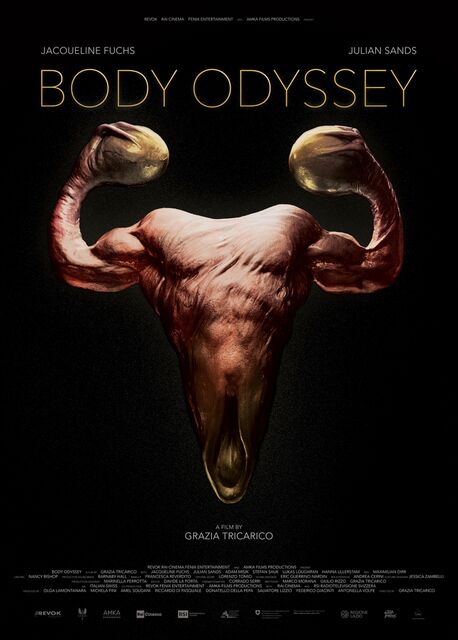

Body Odyssey (2022)

Mona is a female bodybuilder obsessed by an ideal of perfection and beauty. The body is her inseparable container, her most faithful ally, her partner responding to laments. Together they find themselves on the threshold of their destiny.

In Grazia Tricarico’s debut feature, Body Odyssey (2022), a woman’s search for physical perfection takes on both godlike and Sisyphean dimensions. The film, whose style reflects elements of “elevated horror” as well as experimental cinema, presents female bodybuilding as a self-consciously symbolic battleground between what many would likely view as two diametrically opposed conceptions of perfection: Classical femininity and the Herculean teleios of bodybuilding’s own standards of peak physicality. The film’s lodestar is Mona (professional bodybuilder Jacqueline “Jay” Fuchs), a celebrity in her field preparing for her shot at the title of Miss Universe in the over fifty division for the first time. As she trains, pushing her body past its already-hulking standard, her careful psychological equilibrium is shattered, sending her careening into a highly gendered crisis. The film’s tone and style are unique, blending surreal and lyrical passages with clinically observational ones, inviting viewers into Mona’s world but never quite letting us get comfortable in her head with subjective camera work or editing. Oscillating between tone poem and thriller, drama, and satire, Body Odyssey allows viewers to sit with Mona’s crisis of womanhood, probing the contours of a contradiction between external physical standards and authentic self-actualization from multiple sides, freed from the need for narrative resolution. While some may find this untraditional emotional looseness and distance off-putting, even frustrating as plot threads are left dangling, it also creates the opportunity for a distinctive and uniquely open character study of a woman for whom the experience of womanhood is in flux.

From the outset, Tricarico and her co-screenwriters Marco Morana and Guilio Rizzo present Mona’s quest for perfection in stark, black-and-white terms. After several shots of Mona’s almost preternaturally musclebound physique, a gliding camera move shows an overweight man walking slowly on a treadmill. Mona, evidently his trainer, increases the speed until he works his way up to a jog. Another man by a rack of weights asks her about “changing his gain”–– “Maybe you should change your mindset,” Mona replies in her low, husky voice. Mona’s body, then, is a project to her, a companion to her mind rather than its equal. She bends to her will, “building” and “shaping” it with the help of diet, exercise, a steady stream of steroids, and her trainer/guru Kurt (Julian Sands in one of his final roles). On these terms, the body in all its facets, no matter how emotional or psychological, becomes organic matter to be moulded and trained like a pet rather than a genuine extension of the conscious self: Kurt’s regiment for Mona includes transactional sex with a gynecologist alongside green juices and cardio. The mindset required is an almost Zen state of asceticism and self-control that evokes The Substance.

This deprioritization of Mona’s wants and needs as an embodied woman is the jumping-off point for the disequilibrium that overtakes her throughout the film. While her body really starts to go off the rails when Kurt introduces her, largely unwillingly, to a more powerful steroid, her previous dosage has already threatened her reproductive health and induced physical changes that make her dysphoric, namely the enlargement of her clitoris. She’s subjected to frequent transphobic harassment (evoking real-life transphobes’ harassment of cis women athletes who they view as inappropriately “masculine”) as well as experiencing intrusive thoughts of developing a nonexistent beard and other “male” secondary sex characteristics. Her age is another factor in this dynamic to which Tricarico elegantly alludes though never renders didactically. Mona is most often aligned with male bodybuilders in her age group and contrasted directly with the only other female bodybuilder in the film (Hanna Ullerstam), who’s pregnant. Mona is clearly jealous and heartbroken that the younger woman has squared what for her has been an impossible circle, insulting her for her body’s decay from its bodybuilding peak as she herself is openly delirious with fasting for competition. Here it’s clear, then, that traditional “femininity” associated with softness, reproductivity, domesticity, spirituality (this scene takes place at her newborn’s baptism), and weakness cannot be aligned with Mona’s own desire for physicality deemed “masculine,” i.e. as strong and musclebound (though notably aesthetically balanced) as humanly possible, a process that requires draconian discipline. In several fascinating scenes, Mona’s anguish and confusion at her own desire for this ideal is illustrated imagistically. In one, she watches other female athletes on TV and repeats their self-affirming slogans to herself like a manifestation of confidence or self-love (“Why should I hide [my arms]? I do so much training, why shouldn’t I show them off?” she repeats, then gulps). In another, she looks into a mirror wall only to find a waiflike fairy godmother dressed in gold staring back who tells her, “Perfectionism is a dangerous state of mind in this world. Resist this fatal attraction.”

At the same time, Mona’s love of her body as womanly is also clearly contingent on this same strength. The symbiotic relationship between Mona’s body and mind (which she seems to posit as largely dualistic, yet tinged with animism) is the film’s emotional crux and the site of its most experimental flourishes–– details that provide the clearest answers to Mona’s psychological motivations. Mona insists that she “listens” and “talks” to her body, and in the film, her body talks back, first through organic echoing grumbles that mimic both hunger and the cracking, crunching sounds of earth shifting, and then in a low, hypnotic masculine voice whose ideas begin to supplant her own. Her body’s landscape is presented metaphorically as a volcanic seafloor bristling with new life, taking Mona’s Cartesian system of mind-body dualism into more emergentist territory. Eventually, her body becomes its own entity whose will unfortunately wishes to supplant her own when Kurt’s mandates replace Mona’s own (this is a horror movie after all). But before that point and in flashes throughout, Mona is at her most comfortable when “speaking” with her sculpturally toned, gargantuan body, a process associated with dance, water, and her pet cat, all symbols that evoke more familiarly traditional “femininity.” With these associations between Mona’s delicate and affirming self-talk and “femininity” as a construct outside of any practical gender performance or even embodiment, the film suggests that gender is rooted exclusively in one’s own relationship to one’s body and its ability to change to fit one’s desires, a kind of celebratory queer framework made overt through Mona’s struggles with the distrust of those more conventional-looking cisgender characters around her. Kurt’s hijacking of Mona’s bodily discussion–– alongside an unfortunate dalliance with a younger man whose erotic presence haunts her during her celibacy–– are tragic offshoots of her own self-directed quest for beauty rather than signs that the quest itself is wholly misguided. Within this film, then, one can find an empathetic portrait of femininity as fluid and self-fabulated, truer than the external motivators that shape it, be they physical trainers or judgemental lookers-on. As a voice deep within Mona’s body tells her, “Beauty is truth.”

Leave a comment