By Mark Matthews

As writers, we are quick to point out that we are not our characters. We are especially not our villains. When we write someone with major character flaws or sinister traits, that does not mean we are espousing such traits.

That said, every character comes from us and is part of our subconscious, so the characters we create, and the plot points they travel through, says something about our psyche.

In his non-fiction book, Danse Macabre, Stephen King explained he was once asked if there was an event in his childhood that “warped” him into writing horror. King denied there was any one particular incident, but he did share a horrifying story that occurred when he was a child.

According to his mom, he had gone off to play at a neighbor’s house that was near a railroad line. About an hour later he came back and his mom said he was white as a ghost and would not speak for the rest of the day. It turned out that the friend he’d been playing with had been run over by a freight train while playing near the tracks.

King denied the incident propelled him into horror writing, and claims to have no memory of the incident, but novelist and psychiatrist Janet Jeppson, told him “You’ve been writing about it ever since.”1

Well damn! The way King presents it, he infers that Jeppson’s claim is a bit outlandish—of course, he wasn’t writing about it ever since, but can’t it be the main event? Do creators of horror often have some psychological imprint they are therapeutically trying to ‘write out’ in their fiction?

If so, when I look at my own life, it is my life in addiction which was horrifying, and has driven me to write about the topic quite often, as well as publish addiction horror anthologies with other writers. But to dive in deeper, the death of my brother from addiction, while I move on in sobriety, carrying my survivor’s guilt, is perhaps what Jeppson would tell me I have been “writing about ever since.”

I got sober when I was 23, after a harrowing spiral into addiction where, by age 20, I had been waking up drinking every morning, getting my hands on every drug I could. My internal organs were bleeding, my spirit was bleeding worse, so desperate that I just wanted to die. When I started to reach for help, my brother, who was also in his addiction, but, despite interventions, could not maintain sobriety himself, was the one who guided me. It was his AA big book I first picked up, and he directed me to a treatment center where I checked myself into that started my current sobriety run. However, sobriety never took for my brother, so he continued to suffer and died as a direct result of his addiction at age 53.

All of this left a mark.

In my first horror novel, there is one minor character who, throughout the novel, lies dying and suffering after being tortured and abandoned in a drug tunnel. The main characters who come across his wounded body feel sadness for him as he lies bloody and dying, but then they move on. Ultimately, his death at the end is tragic but puts a stop to his perpetual suffering. It was almost mercy.

It was many months later I thought to myself: “My God, that is my brother Kevin.” Tortured in life, always so alone, and when he finally died it was tragic, but ended a life of suffering.

My novella, Body of Christ, features a character who is on life support after a major car accident, and their family decides to end this life support. Just as this is happening, the character’s daughter imagines them screaming from the hospital, “Stop! Stop! I’m still alive, I’m still in here. “

Once again, it wasn’t until well after this work was published I realized this was triggered by the death of my brother. While it seems so obvious, I had blocked it out.

My brother was on life support before he died, his brain activity such that he would never recover and be functional, and we made the decision to cease these means of keeping him alive. And despite what you see or hear, someone does not pass immediately when you pull the plug, it takes many hours (and can take days) of watching their breathing labor, and their vitals weaken.

The guilt and trauma were all there in my fiction. And it’s all still there.

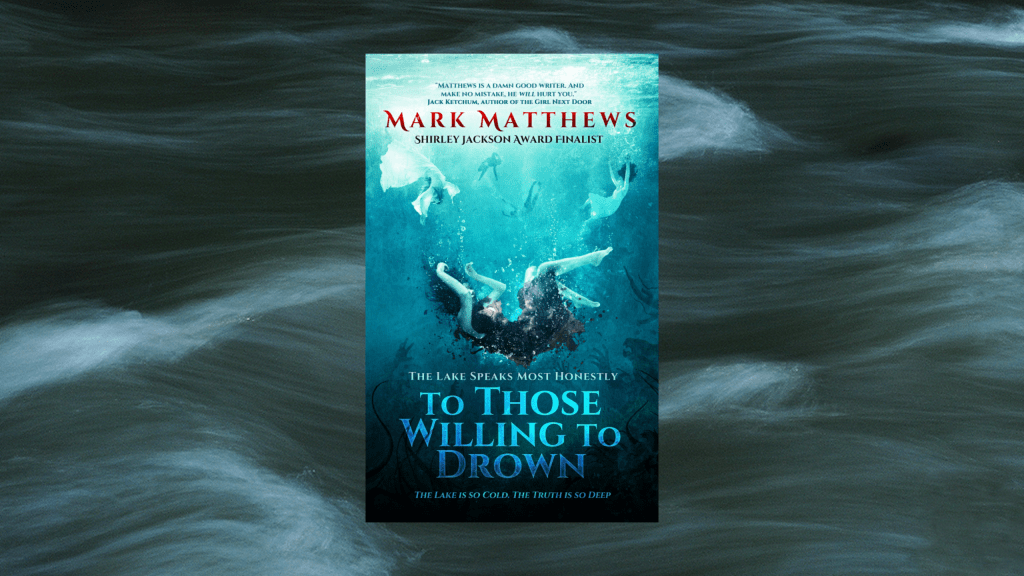

My upcoming novel, To Those Willing to Drown, is about the scattering of ashes and the afterlife, and I like to think this piece of fiction is where I move on to accepting my brother’s spirit is in a better place. My parents kept his ashes in an urn on the mantle, and we often spoke to the urn as if my brother was still there inside, going so far as to imagine his spirit speaking back to us from the ashes. And this is what happens in my novel. In fact, the novel was originally called “Our Souls Remain in the Ashes”

Part of the novel’s premise (spoiler alert) is that once you sprinkle someone’s ashes in Torch Lake (Torch Lake is a place my family spent many summers) the soul comes to life (but must remain in the water). The water is a sanctuary, a heaven, and loved ones can even visit at night by shining a flame towards the water’s surface, and your loved one will appear.

This was my way of coping with loss, for there is a lot of death in the novel, plenty of addiction, and more than enough guilt, but even though so many die, there’s a happy resolution, for the souls inside are eternal and reunited after death.

But oh, the dark side of life will always match the dark side of fiction.

After I was done with the first draft of To Those Willing to Drown, my dad passed away after 84 years of a very full life. Rewriting the novel gave way to me writing his eulogy.

A family friend who lives on Torch Lake brought a bottle of lake water downstate, put it in my dad’s casket before he was cremated, and it is now part of his ashes. We buried both my dad’s and brother’s urns in a cemetery, to honor his wishes, but the metaphysics of it still haunts me.

Shouldn’t ashes be spread in the earth, instead of trapped in an urn forever? If their soul remains in the ashes, aren’t they also forever in that urn? Eternally stuck inside, alone and suffering. Of course, I don’t really believe it, but this is how I think, and the concept of it haunts me.

So when I pass, my ashes will be spread, not left in an urn, but before then, there is more to trauma to deal with, more fiction to write, because nobody here gets out alive. We all have friends run over on the metaphorical railroad tracks. The music never stops in our danse macabre.

Check out To Those Willing to Drown, where, in order to save her child’s soul, a grieving mother must battle a sinister pastor who haunts a lake community. Coming this spring.

“A powerful, thought-provoking, multifaceted story that proves nearly impossible to put down.” —D. Donovan, Senior Reviewer, Midwest Book Review

Mark Matthews is a graduate of the University of Michigan and a licensed professional counselor who has worked in behavioral health for over 25 years. He is the author of On the Lips of Children, All Smoke Rises, Milk-Blood, and The Hobgoblin of Little Minds. He is the editor of a trio of ‘addiction horror’ anthologies including Orphans of Bliss, Lullabies for Suffering, and Garden of Fiends. In June of 2021, he was nominated for a Shirley Jackson Award. His next novel, To Those Willing to Drown, is coming in 2025.

Leave a comment