L. Marie Wood

None of this is new.

Black creators have always been, effectively, put in a box, allowed to produce, but the resulting work was shunned, criticized, or outright ignored. Accomplishments such as the first Black person to win a starring role in a motion picture, in the case of Clarence Muse, go unheralded in history, not unlike the scientific, medical, and aeronautical contributions of Black people that are routinely muted. Black people are represented as servants, beggars, and vagrants on film with alarming frequency and without counter. This lack of wholistic representation in media impacts the way that Black people are perceived in the real world, creating repercussions that go beyond entertainment, the horror genre included. The absence of Black people in horror movies that reflect normal daily life imparts the same message and, in turn, garners the same response. This lack of visibility serves to perpetuate the idea structure of Black people being inferior: other. These mindsets are easily reinforced by the human propensity to believe what is shown or told to them without critical assessment and/or research on their part to corroborate the sentiment as fact.

Black people are rarely shown in a realistic light in film, horror or otherwise. So Black people created their own.

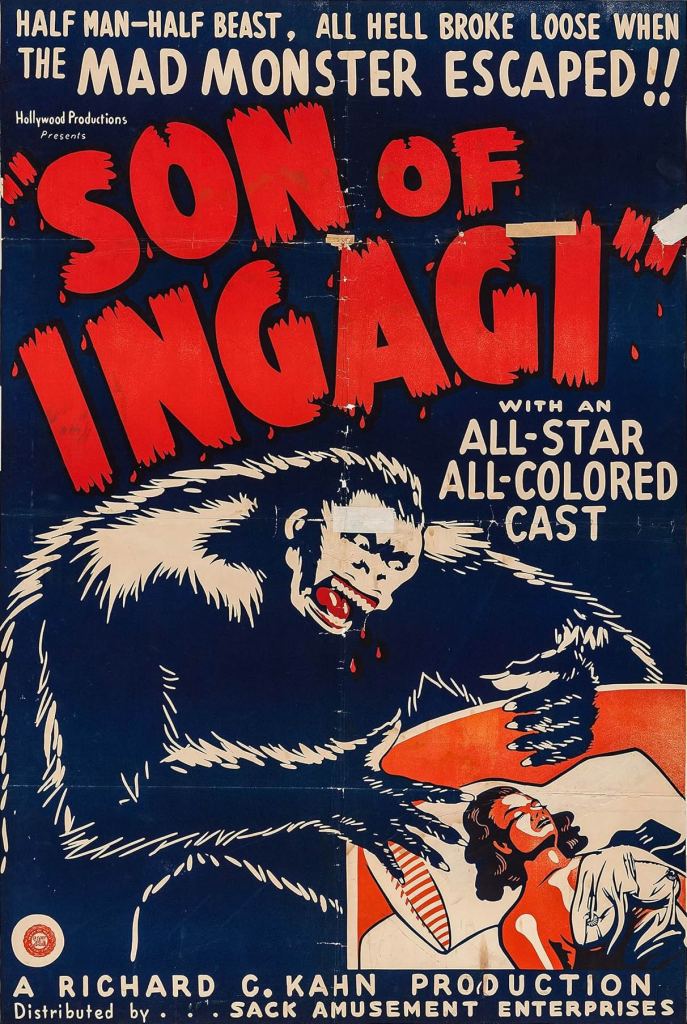

Son of Ingagi is the first horror film to feature an all-black cast. Released in 1940, the monster is a creature brought back from one of the doctor’s excursions abroad. The creature is kept in the basement of the house and, upon drinking a potion found there, turns murderous and slays her. An unwitting couple inherits the home and later discovers the creature in residence. This film was written by Spencer Williams, a pioneer in the Black producer and director spaces as well as an accomplished actor in his own right. This film, as well as the work of Oscar Micheaux, who is generally regarded as one of the most successful African American filmmakers of all time, is part of a genre of movies called race films.

Race films were movies that were produced with Black audiences as the intended market. They were often comprised of all or predominantly Black casts and had a Black crew, producers, writers, and directors attached. They showcased Black people in a variety of roles, countering traditional depictions of Blackness onscreen, dispelling the stereotypical and disparaging precedents set in movies where White actors appeared in blackface, where Black people quietly tended to the duties of servitude in the background, or where they were omitted from society altogether. The need for race films speaks of the response to the oppressive machine that relegated Black imagery to lesser or “other” status. While race movies were a product of segregation, they stoked a desire to produce images depicting Blacks as real people rather than as caricatures of themselves, in equal part subservient, buffoonish, and villainous, and to have some control over the messages being propagated, consumed, and internalized by other races, as well as their own.

The 1970s brought in what were called blaxploitation films, a genre named as such by NAACP Chapter president Junius Griffin (Sims). Professor and author of Women of Blaxploitation: How the Black Action Film Heroine Changed American Popular Culture, Yvonne Sims determined that over 200 movies under this umbrella were created by the midway point of the 1970s in many genres including action, westerns, comedy, drama, and horror, all of which featured stereotype-busting characters that were “self-possessed Black men… in control of their own destinies.” There were many horror gems produced during that era, such as Ganja and Hess, Blackenstein, and Blacula. While these movies are largely considered to work in the extremes, films like Dr. Black, Mr. Hyde had Black characters who were doctors, scientists, detectives, pimps, prostitutes, business owners, and average Joes. This kind of variegated approach to moviemaking presented a kaleidoscope of human experience through a Black lens that had not yet been portrayed on screen.

And then what?

A curious situation unfolds as we review the history of Black film. The race films of the early 20th century did not change the mindset of society about Black people and our contribution to entertainment. The blaxploitation films produced prolifically in the middle of the 20th century have problematic undertones that impede the genre’s legitimacy in scholarly study. The effectual role reversal that the exaggerated masculinity, bravado, and inherently “hip” demeanor that many of the actors portrayed in blaxploitation films didn’t help matters. It had an opposite effect, one that perpetuated the concept of a marked difference between communities, encouraging the idea that there is little to no common ground between Black and White people. The focus on showcasing these differences and celebrating them in a manner that appeared antagonistic, critical, and disparagingly humorous further cemented the notion that there is an “other.” This practice alienated White viewers, having a polarizing effect as opposed to a unifying one. What was discovered was that characters created to embody the stereotypical characteristics that society has been groomed to recognize as Black perpetuates the same problem that the concept of tokenism does: they create a false reality of acceptable Blackness and paint a whole subset of people with the same brush. This practice results in effectual segregation of Black and White people inasmuch as separate products for separate audiences do.

As the 1980s dawned, Black filmmakers searched for new ways to showcase Black people and Black life. The newest foray into this effort, from a speculative fiction standpoint, is Black Horror. Black Horror is the natural extension of race films and blaxploitation movies in the contemporary market. With a cast and crew that is predominantly Black, this genre boasts movies like Def by Temptation, the Tales from the Crypt film Demon Knight, Eve’s Bayou, Tales from the Hood, and Bones. Films in the Black Horror genre in the 1980s and 1990s took a page from the blaxploitation era, producing films that served as racial delineators, adding fodder to the argument of segregation—or separation. At the same time, some concepts made it out into the world that inadvertently perpetuated stereotypes set in place by White filmmakers years before.

The 1992 release of the movie Candyman did a lot of things at one time: It cemented a Black character as a terrifying antagonist who is as formidable as his press suggests; it featured a Black character with staying power, considering how few minutes he appeared onscreen; it secured an irrational fear in the back of every viewer’s mind, regardless of age, race, or creed—one that made them remember what would happen if the warning not to summon him is ignored. It also revealed some of the racial biases that exist within the Black community, putting them on display and creating a polarizing canvas on which Black people were torn about how to feel.

One might assume that the lynching of the character Daniel Robitaille, or perhaps even the twin communities of Cabrini Green, where the Black people reside, and the upscale apartment complex where the lead character, Helen Lyles, lives—the two dwellings separated primarily by socioeconomic status—and the resulting consternation, was what was being dissected, but there was a more insidious point to be made with this film. The glimpse into the brutality of racism is artfully displayed, forcing moviegoers to reckon with what occurred in order to experience the story they paid to see. Then a muted form of racism came to the foreground: a microaggression within the Black community was displayed in startling clarity, one that sowed the seeds of the kind of racial honesty that films like Jordan Peele’s Get Out and Us harvested, when Bernadette, doomed Black sidekick of Helen Lyles, was lumped into the collective “White folks” bucket by Anne-Marie, the mother of the child who would later be kidnapped by Candyman. Even though she was Black, Bernadette was not seen as such because of the nature of her presence in Cabrini Green—her appearance and reason for being there were at the forefront, even before her shared racial makeup.

The 2000s represented a new, more outspoken version of Black Horror and Black characters in horror. Scream 3’s Tyson Fox character, who was an actor cast in Stab 3, the movie within the movie, had interactions with his White counterparts that did not portray him as subservient or “other.” Black filmmakers continued to create their own movies and submitted entries that garnered mainstream audiences, including the Scary Movie franchise created by the Wayans brothers that successfully linked horror and humor. Black actors found more work that did not force them to perpetuate the stereotypical behavior to which their counterparts in the early 1900s were relegated. Black stories were being told in a more mainstream and consumable way, but there was still a chasm between the understanding of experiences that a diverse lens could provide to mainstream viewers. The 2017 release of Jordan Peele’s Get Out changed the vantage point of Black Horror and its underpinnings rooted in racism, discrimination, and classism. It gave life to the idea of elevated horror. This groundbreaking film also reinforced the concept of disparate fear in a meaningful way.

What people consider scary relies on several factors, including history and environment among them. Black people in the U.S. have different triggers that incite fear in them, ones that may be different from people from other racial backgrounds even if they are close in age, even if they are members of the same community. Being followed in stores, not being believed by those in positions of authority, not being allowed to be a child, such as in the 1955 case of Emmett Till, who was brutally murdered after being accused of menacing a White woman, an accusation that was recanted decades after his death, and in the 2014 case of Tamir Rice, who was killed while playing with a toy gun—these scenarios spark terror in the minds of Black people, ordering their steps in a manner that precludes carefree living. This is markedly different than the traditional offering of ghosts, goblins, and supernatural beings that make up the mainstream horror genre. While those characters present opportunities for escapism in the form of entertainment for many Black people, they do not represent true fear that is visceral or that has a lingering impact.

The aforementioned breakout movie, Get Out, a movie rife with Invasion of the Body Snatchers vibes, crafts a tale of shattered illusions and the body coveted that manages to bring to life the very real fear that Black Americans experience at some point in their lives: the worry that something isn’t as it seems. Audiences came together to watch the horror film as they did in the 1980s; they were able to scream directions to the screen, talk with the people around them about what was happening in the story, and react out loud as a result of this shared experience. The difference this time was that both Black and White audiences could see themselves on screen, see the truths and exaggerations for what they were, and take away messages that were fodder for open discourse once the lights came on.

Black Horror films continue to gain their footing in this new space created by Peele’s thought-provoking movies. Some entries continue the work, bringing imagery to the screen that reflects realistic Black characters. An example of this includes Osei-Kuffour Jr.’s 2020 science fiction horror release, Black Box, about a man who struggles to put fragments of his memory together after a tragic accident. Others have gone further, focusing on “more” rather than “what”, bringing about an informal subgenre of Black Horror aptly referred to as trauma porn. Releases such as Antebellum in 2020 and Amazon’s limited series Them in 2021 represent examples where the continued aggression toward the Black characters overrides the horror elements.

Black Horror – its very definition – is changing as movies are released and old ideas are revisited. The 2019 movie Ma, about a Black woman who was humiliated as a teenager, sets an elaborate trap for the children of those who harmed her, subverts the trope of the Black character dying first, instead taking a page out of Candyman’s book and casting the Black character as the antagonist. There are also inroads being made in cable/streaming television with the 2020 release of Lovecraft Country, which was developed by Misha Green, a Black woman.

There is something to be said about the influx of images that portray Black characters doing the same things that White characters do, and the movies coming out reflect that shared existence. It is empowering, regardless of how controversial the execution may be.

Leave a comment