By Tuğçe Kutlu

The roots of horror are deeply entwined with Gothic literature, a genre born from the shadows of the Enlightenment. As Twitchell (1985) noted, modern horror’s origins lie in the late 18th century, with its ability to provoke “dreadful pleasures,” stirring powerful emotions buried deep within the human spirit. Gothic literature emerged as a response to the rationality of the Enlightenment, as Romanticism offered a creative outlet for suppressed feelings (Clasen, 2017). The Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason often dismissed emotional and spiritual experiences, leading Romanticism to embrace the irrational and the sublime. Like Frankenstein’s monster, the Gothic novel came to life, its heart beating with dread and sorrow.

At the center of Gothic horror lies the uncanny—the intersection of the familiar and the unfamiliar, as described by Freud (1919). Themes of haunted homes, grieving families, and otherworldly specters dominate the genre, reflecting the Victorian obsession with death and decay. As Joseph and Tucker (1999) explain, Victorian England grieved the loss of its spiritual fixtures amidst the modern age’s rapid changes. Even Queen Victoria herself embodied this era’s fixation on mourning, her very public grief for Prince Albert symbolizing a broader cultural preoccupation with loss (Kerrigan, 2007). Elisabeth Bronfen (2009) aptly described this fixation as “death by proxy,” where audiences confront mortality through narratives or visual art. Horror functions on a similar premise, allowing viewers to experience grief and fear at a safe distance.

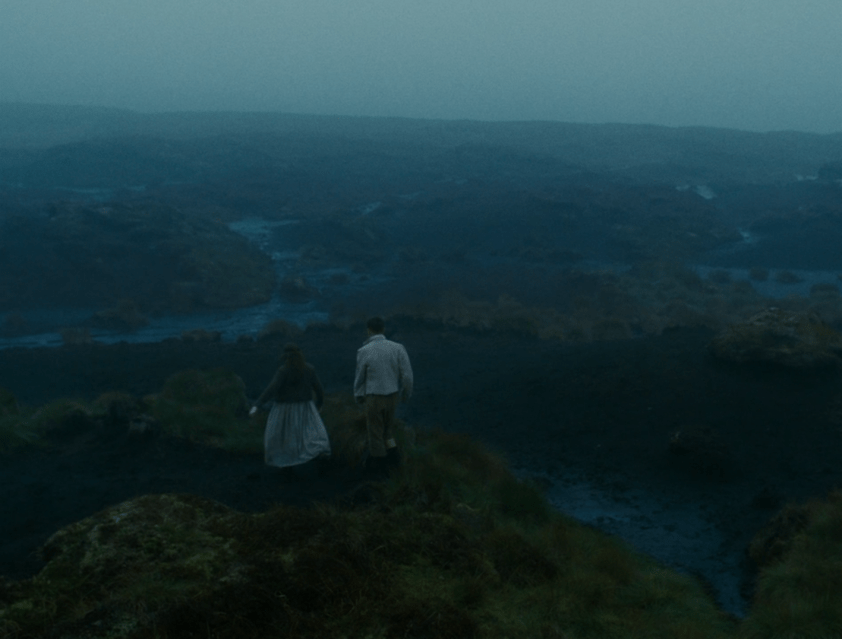

Gothic literature has long been a canvas for exploring grief, and its hallmarks are reflected in the tormented characters that populate these stories. For instance, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) explores Victor Frankenstein’s anguish over the deaths caused by his creation, mirroring a profound sense of guilt—grief’s frequent companion. This link between guilt and loss underpins much of Gothic fiction (Clasen, 2017). Similarly, Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (1847) presents characters like Heathcliff and Catherine Earnshaw, whose shared obsession and the grief stemming from their separation perpetuate cycles of vengeance and suffering. These narratives exemplify how grief transcends individual tragedy, becoming a haunting legacy.

Freud’s concept of the uncanny offers insight into why Gothic horror resonates so strongly. Death is both familiar and alien, embodying a paradox that Gothic works exploit to evoke unease (Freud, 1919). Through settings such as crumbling castles and fog-drenched moors, Gothic horror externalizes grief, turning internal anguish into atmospheric dread. The spectral presences that haunt these tales—ghosts, echoes of the past—serve as literal manifestations of loss. This dynamic is also evident in Edgar Allan Poe’s works, such as The Raven (1845), where the narrator’s grief over Lenore is transformed into a haunting, repetitive presence.

While grief has rarely been the focus of academic studies in horror cinema, several scholars have acknowledged its centrality. Susanne Kord (2016) argues that horror often focuses on guilt, which is inherently tied to the grieving process. Films such as Don’t Look Now (Nicholas Roeg, 1973) encapsulate this theme, centering on a grieving father haunted by the death of his daughter. The film’s recurring imagery—shadows of the deceased, foreboding premonitions—highlights how grief permeates the protagonist’s psyche. Kast (1988) aptly notes, “When a loved one dies, we not only experience our own deaths in an anticipatory way through this event; in a certain sense, we also die with him.”

Similarly, Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960) offers a portrait of grief twisted into pathology. Norman Bates’s inability to process his mother’s death leads him to create a haunting substitute—an embodiment of Freud’s notion of “melancholia.” Unlike mourning, where the mourner remembers the object of loss, melancholia creates psychological paralysis, trapping the mourner in unresolved grief (Freud, 1917).

Richard Armstrong’s Mourning Films (2012) draws compelling parallels between grief and horror. He observes that both genres tap into primal fears—darkness, ghosts, and the unknown—and translate them into psychological themes like hallucinations, dementia, and the vulnerability of children. These themes are apparent in films like Hereditary (Ari Aster, 2018), where a grieving family spirals into supernatural chaos. The boundaries between the real and the uncanny blur, with the pain of grief amplifying the horror. The film’s use of unsettling visuals and jarring sound design externalizes the family’s internal anguish, aligning it with Gothic traditions.

Even in the visceral world of slasher films, grief serves as a driving force for horror. In Friday the 13th (Sean S. Cunningham, 1980), Mrs. Voorhees’s transformation into a killer is rooted in her unresolved grief and guilt over her son’s death. As Sanders (1999) notes, parents grieving the loss of a child often experience prolonged feelings of guilt, whether rational or not. This blend of grief and guilt gives Mrs. Voorhees’s rampage a tragic undercurrent, adding psychological depth to the film’s carnage.

Likewise, the Scream series (Wes Craven, 1996–2011) positions grief as the cornerstone of its narrative. Sidney Prescott’s journey is defined by mourning—not just for her mother, but for every friend and ally lost along the way. Maureen Prescott’s shadow looms over the franchise, with her death triggering Sidney’s spiral into survivor’s guilt. From hallucinations of Maureen in Scream 3 to Sidney’s nickname as the “Angel of Death” in Scream 4, her grief remains inseparable from her identity. Craven’s self-reflexive approach transforms Sidney’s mourning into a meta-commentary on the genre itself—where the trope of grief is deconstructed but never dismissed.

While grief has long lingered in the shadows of horror, modern Gothic films bring it to the forefront. The Babadook (Jennifer Kent, 2014) explicitly intertwines grief with the supernatural. Amelia, a grieving widow, confronts her anguish through a literal monster—a manifestation of her unresolved emotions. The film’s oppressive atmosphere, characterized by shadowy visuals and dissonant soundscapes, externalizes Amelia’s inner turmoil, aligning with Gothic traditions.

Comparably, Midsommar (Ari Aster, 2019) explores how communal rituals amplify and distort individual grief, creating horror from shared trauma. The film’s sunlit yet unsettling imagery contrasts with traditional Gothic darkness, modernizing the genre while retaining its thematic core. This evolution underscores how loss transforms us, reshaping the genre for contemporary audiences.

From the decaying mansions of Gothic novels to the haunted psyches of horror films, grief is an ever-present specter in the genre. Whether lurking in the shadows of slasher films or emerging as a central theme in psychological horror, grief connects audiences to the uncanny and the sublime. Gothic horror, with its timeless exploration of loss and sorrow, reminds us that fear and grief are eternal companions—and that confronting them can be both terrifying and cathartic.

References

Armstrong, R. (2012). Mourning Films: A Critical Study of Loss and Grieving in Cinema. McFarland & Company.

Bronfen, E. (1992). Over Her Dead Body: Death, Femininity and the Aesthetic. Manchester University Press.

Clasen, M. (2017). Why Horror Seduces. Oxford University Press.

Freud, S. (1917). “Mourning and Melancholia.” In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XIV (1914-1916): On the History of the Psycho-Analytic Movement, Papers on Metapsychology and Other Works, pp. 237-258. The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

Freud, S. (1919). “The Uncanny.” In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XVII (1917-1919): An Infantile Neurosis and Other Works, pp. 217-256. The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

Joseph, M., & Tucker, G. (1999). “The Victorian Mourning Culture: The Art of Grief.” In The Material Culture of Death in Victorian England, pp. 1-28. Indiana University Press.

Kast, V. (1988). Grief and Its Impact: The Dynamics of Mourning. Texas A&M University Press.

Kerrigan, M. (2007). The Dark Side of Victorian Life. National Archives.

Kord, S. (2016). “Horror and Guilt: The Pathological Dimensions of Fear in Film.” In The Horror Film: An Introduction, pp. 85-102. Wiley-Blackwell.

Sanders, C. M. (1999). Grief: The Mourning After: Dealing with Adult Bereavement. John Wiley & Sons.

Twitchell, J. B. (1985). Dreadful Pleasures: An Anatomy of Modern Horror. Oxford University Press.

Leave a comment