Few things are as chilling as the relentless gaze of someone who just can’t let go. In horror, stalkers and obsessive fans push the boundaries of fear, making us question who’s watching from the shadows or lurking outside the door and in the age of social media, who’s behind the screen? These 5 horror thrillers dive into the terrifying obsession of individuals who refuse to pull back, each pulsing with an unsettling reminder: some of us WILL push for the reciprocation we feel we deserve.

But while these films explore the disturbing consequences of unchecked fandom and obsession, it’s crucial to remember that celebrities aren’t our real friends. The relationship between fans and celebrities is inherently transactional. No one owes anyone access to their life, no matter how close they think they are. These films serve as cautionary tales, showing us how the blurring of boundaries can lead to real life harm, escalating violence and in the most extreme cases, murder. The dangers of entitlement and obsession are real, and these narratives are stark reminders of the need for healthy, respectful admiration rather than an illusion of possession.

Misery (1990) – Written by William Goldman based on the novel by Stephen King, Directed by Rob Reiner

Rob Reiner’s Misery (1990) is the definitive stalker-fan horror film, capturing the terrifying power imbalance between creators and their most obsessive followers. James Caan plays Paul Sheldon, a successful author known for his Misery series – a set of historical romance novels with a devoted audience. He’s eager to break free from his popular franchise and established himself as a serious writer. Unfortunately, his biggest fan, Annie Wilkes, played by Kathy Bates in her Oscar winning performance, has other plans.

Annie isn’t just a devoted reader; she’s a walking embodiment of parasocial obsession. She believes Paul’s work belongs to her, and when she discovers he’s killed off Misery in his latest book, she doesn’t just complain, she kidnaps him. She keeps him captive in her isolated house, forcing him to rewrite the novel to her liking. The dynamic between Annie and Paul mirrors the worst aspects of fandom entitlement, where audiences feel ownership over a creator’s vision and react violently when it doesn’t align with their expectations. Sound familiar? Just look at modern toxic fandoms where social media gives every disgruntled viewer a platform to harass writers, directors, and creatives alike.

What makes Annie so terrifying is her unpredictability. One moment she’s doting on Paul like a loving caregiver, calling herself his “number one fan”, the next she’s smashing his ankles with a sledgehammer in one of horror’s most brutal scenes. Bates’s performance is chilling because she never plays Annie as a straightforward villain. She’s tragic, lonely, and deeply deluded. Her obsession with Misery is more than just fandom, it’s the foundation of her entire identity. Reiner’s direction traps the audience with Paul, making Annie’s home feel incredibly claustrophobic. The film isn’t just psychological horror, it’s also a commentary on artistic agency, toxic admiration, and the blurred lines between love and control. Paul survives, but Misery lingers as a reminder that sometimes the scariest monsters aren’t supernatural, they’re just people who love your work a little too much.

The Fan (1981) – Written by Bob Randall, Priscilla Chapman and John Hartwell, Directed by Ed Bianchi

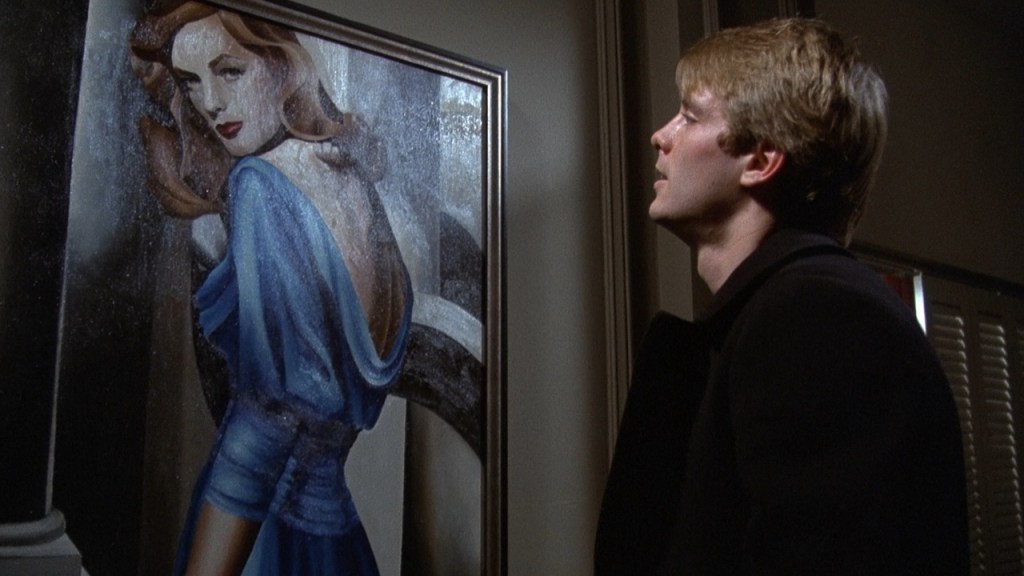

Long before social media gave us real-time access to our favorite celebrities, The Fan (1981) warned of the dangers of fans who think admiration equals entitlement. This lesser known stalker thriller, directed by Edward Bianchi, stars Lauren Bacall as Sally Ross, a glamorous Broadway actress whose biggest admirer, Douglas Breen (Michael Biehn), believes he has a special connection with her. When she doesn’t reciprocate his attention because, you know, she’s a normal person with boundaries, he turns violent.

Douglas represents the dark side of celebrity obsession. At first, he sends Sally letters expecting a response. When she doesn’t reply, his love curdles into resentment. This transformation is disturbingly real. Stalkers often start as super fans before feeling rejected and lashing out. The film taps into the idea that certain individuals can’t distinguish between personas and private lives. To Douglas, Sally owes him something for his devotion. It’s the same mindset that fuels modern Internet harassment, where fans feel entitled to access, validation and control over celebrities and in this day and age, regular Joes like you and me.

While The Fan has some campy moments, especially with Bacall’s glamorous theatricality, it also delivers some genuinely unsettling scenes. Douglas escalates from creepy letters to full blown violence, proving that obsession can be deadly. The film’s biggest strength lies in its terrifying impressions. It came out decades before we had to worry about social media doped stalkers, yet it perfectly captures the entitlement and resentment that brew in the darkest corners of fandom.

Cape Fear (1991) – Written by John D. MacDonald, James R. Webb, and Wesley Strick, Directed by Martin Scorsese

If Misery is about fan obsession and The Fan is about audience entitlement, Cape Fear (1991) is about vengeance that festers into an all-consuming obsession. Martin Scorsese’s remake of the 1962 thriller stars Robert De Niro as Max Cady, a convicted rapist who, after 14 years in prison, seeks revenge on his former lawyer Sam Bowden, played by Nick Nolte. But Cady isn’t just out for justice; he wants to psychologically and physically dismantle Sam’s life.

De Niro’s Cady is terrifying because he enjoys the process of tormenting Sam and his family. He slithers into their world, not just threatening them, but embedding himself within their vulnerabilities. His manipulation of Sam’s teenage daughter Danielle, played by Juliette Lewis, is particularly unsettling, demonstrating how abusers groom and psychologically entrapped their victims. Lewis and De Niro’s infamous scene where she seductively sucks on his thumb is one of the most uncomfortable moments in 90s cinema.

Cady also explores guilt and justice. Sam isn’t an innocent man; he buried evidence that could have helped Cady in court. Does that justify Cady’s reign of terror? Absolutely not! But the film plays with moral ambiguity, making Sam question whether his own corruption led to his downfall. It’s a chilling study of power, predatory behavior and paranoia.

Single White Female (1993) – Written by John Lutz and Don Roos, Directed by Barbet Schroeder

If you’ve ever had a roommate who just didn’t get boundaries, Single White Female (1992) will hit waaaay too close to home. Directed by Barbet Schroeder, this psychological thriller is one of the defining films about obsessive female friendships gone terribly wrong. It starts Bridget Fonda as Allie, a successful software designer who, after breaking up with her cheating fiancé, seeks a new roommate. Enter Hedy (Jennifer Jason Lee), who seems sweet, supportive and perfectly normal…until she isn’t.

Hedy’s obsession with Allie starts out subtly. She complements her clothes, asks personal questions, and offers emotional support when Allie is vulnerable. But things quickly escalate. She starts mirroring Allie – first in dress, then in hair style, until she’s practically a clone. The transformation is chilling because it’s rooted in something deeply psychological: identity envy. Hedy doesn’t just admire Allie; she wants to be her. And when admiration turns to possession, Allie realizes she’s not living with a friend, he’s living with the threat.

What makes Jennifer Jason Lee’s performance so terrifying is that she never plays Hedy as a monster, at least not outright. There’s a deep sadness to her obsession, stemming from trauma and abandonment issues. Her need for connection is so intense that she consumes Allie’s life like a parasite, unable to distinguish between love and possession. This makes her even scarier than the traditional horror villain because she’s not mindlessly evil. She’s desperate, unstable, and tragically human.

Barbet Schroeder crafts a tense atmosphere where the apartment, once a place of safety, becomes a psychological battleground. The film plays with the fear of intimacy turned toxic or closeness with the wrong person can strip you of your sense of self. When Hedy finally turns violent, it feels inevitable, as if she’s been emotionally stalking. Really long before the physical attacks begin, and perhaps long before she’s even moved in. Beyond the thriller elements, Single White Female serves as a metaphor for identity loss, personal boundaries, and the dangers of ignoring red flags and relationships, platonic or otherwise, especially when we’re at our most vulnerable.

Fear (1996) – Written by Christopher Crowe, Directed by James Foley

If the 90s had a cautionary tale for teenage girls dating bad boys, Fear was it. On the surface, it plays out like a steamy teen romance until it very quickly becomes a full blown psychological horror about possessiveness, control and domestic abuse. Directed by James Foley, Fear stars a young Reese Witherspoon as Nicole, an innocent 16 year old who falls for Mark Wahlberg’s David, a seemingly charming older guy who, spoiler alert, is not boyfriend material.

David starts out as a dream bad boy: attractive, rebellious and protective. He showers Nicole with affection, listens to her problems and wins over her friends. But his devotion soon turns too intense. He gets jealous of her male friends, pressures her to be alone with him, and reacts aggressively whenever she asserts her independence. Sound familiar? That’s because Fear perfectly encapsulates the cycle of abusive relationships: love bombing, control, and eventually violence.

What makes this film so terrifying is how realistic David’s manipulation feels. He doesn’t show his true colors right away; He eases Nicole into his control, isolating her and making her doubt herself. When she finally realizes the danger, it’s too late. David has fully embedded himself into her. Life. And he’s not letting go. Wahlberg, in one of his earliest roles, plays David with chilling intensity, balancing his charm with an undercurrent of menace (and I suppose if you know, you know, maybe he wasn’t really acting). The moment he smashes his head into a mirror After Nicole rejects him is a HUGE red flag. Not that there weren’t dozens before that.

One of the film’s most infamous scenes is the roller coaster sequence where David plays hide the fingerbørg with Nicole while “Wild Horses” by The Sundays plays. At first, it feels romantic and exhilarating, but in retrospect, it’s deeply unsettling. It symbolizes David’s intoxicating control over Nicole, manipulating her emotions while making her feel like he’s the only one who truly understands her.

But Fear isn’t just about David and Nicole. It’s also about parental fear. William Peterson plays Nicole’s father, Steve, who immediately senses something is off about David. His growing panic mirrors the real life helplessness many parents feel when watching their children fall into toxic relationships. The film does a fantastic job showing abusers don’t just target their victims, they infiltrate entire families, playing the role of the perfect partner until they secure their control.

The third act turns into full blown home invasion horror as David, furious at being rejected, brings his gang of equally unhinged friends to Nicole’s house, ready to take her back by force. The violence is brutal, the tension is suffocating, it cements Fear as more than just a thriller: it’s a warning.

David represents every charming predator who preys on vulnerability, twisting love into control. At its core, Fear is a film about obsession masquerading as love, showing how quickly a fairy tale. Romance can become a nightmare. It remains an unnerving watch, not just for its suspense, but how eerily real it feels. Because let’s be honest, every teenage girl has at some point ignored the warning signs of a bad boy and Fear is here to say, maybe just don’t.

These films don’t just depict stalker narratives for shock value, they expose the terrifying reality of parasocial relationships or one-sided bonds where the fan believes they know the person on the other side. But admiration isn’t the same as ownership, and affection doesn’t equal obligation. When fans begin to demand access, control, or even retribution against the people they idolize, they reveal how entitlement can morph into obsession. These films show the horrors of crossing those boundaries, but they also serve as a much needed reality check: celebrities aren’t your friends, and no matter how much someone shares online or in interviews, that doesn’t grant unlimited access to their lives.

Leave a comment