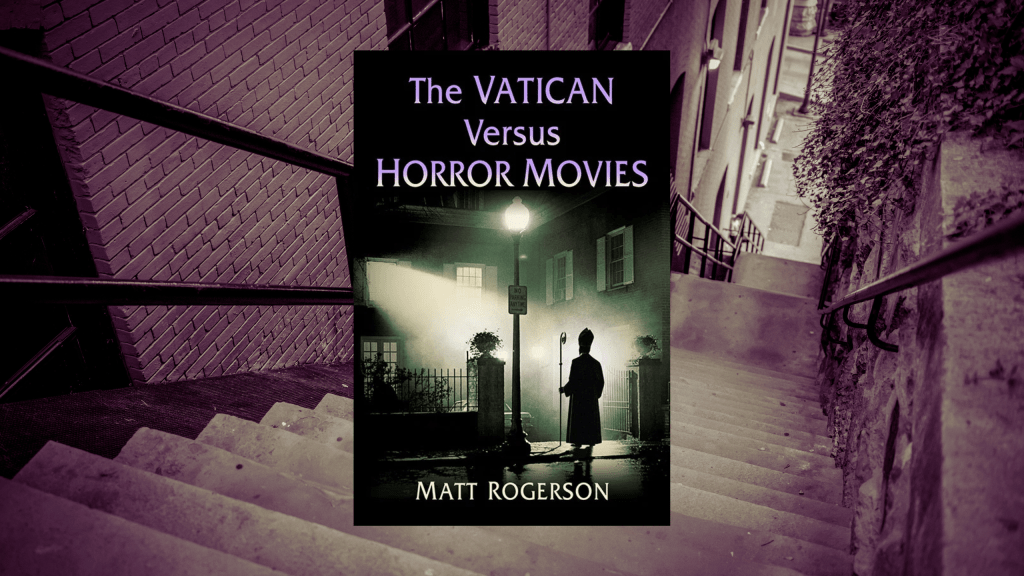

“The Vatican Versus Horror Movies” by Matt Rogerson is a deep dive into the Catholic Church’s historical battle against horror cinema. From Gothic horror to slasher films, giallo, and Satanic Panic, this book explores how the Vatican condemned and attempted to control horror’s most controversial subgenres. Featuring newly translated Church film reviews, Rogerson uncovers how horror filmmakers responded—sometimes by making the clergy the villains. We sat down with the author to discuss researching the Church’s impact on horror history, and why these films remain so culturally significant. A must-read for horror scholars and cinephiles alike.

What initially drew you to the Segnalazioni Cinematografiche, and how did the idea of translating and contextualizing them evolve into this book?

I was doing some research for what has now become my 2nd book, about Italian director Lucio Fulci, when I came across a journal paper that mentioned the Segnalazioni Cinematografiche in passing, merely stating that it was the Vatican’s own film review journal and that it had made negative comments about a particular film. There was frustratingly little information about the Segnalazioni Cinematografiche, as these journals had never been disseminated outside of Italy or translated into English before, but I became obsessed with tracking them down. Over time, I pieced together what turned into a potted history of the Vatican’s attempts to control the distribution and exhibition of film in Italy. From there, I started looking for editions of the Segnalazioni Cinematografiche from certain years, to see if there was anything of note in there that I might be able to use. As it turned out, the Vatican’s reviews were pretty eye-opening and it quickly became clear that its opposition to many films was political rather than anything to do with the Bible or the Catechism of the Roman Catholic Church. It was from here that the idea formed – what did the Vatican think of Rape/Revenge films, for instance? Knowing that the Roman Catholic Church has held some…problematic opinions about rape, I expected their pastoral reviews of these films to betray some hypcrisies, and I wasn’t disappointed! It soon became apparent that I would have enough material for an entire book, and I decided to make this my first book and return to my other manuscript later.

The back issues of the Segnalazioni Cinematografiche were very difficult to find! Some I came across on Italian ebay, but more commonly I had to peruse various Italian used book emporiums (both online and in Italy, where I made various trips to Milan and Rome to search them out). Now I am the proud owner of in the region of 50 of these journals, dating all the way back to the first ever journal that covered late 1934-early 1935).

In examining the Vatican’s responses to horror films, did you find any particular trends or hypocrisies that stood out across different decades?

Mostly I found trends and hypocrises across different genres and subgenres of film. For instance, their responses to Nunsploitation films were of great interest, as many such films (The Nun of Monza, Beatrice Cenci, Flavia The Heretic, The Devils) were based on real life occurrences whetre the Church famously abused women in its ranks. So writing in opposition of these films was a difficult task for the Vatican, given it was complicit in so many of their real life stories. The same goes for Nazisploitation films, as of course the Vatican signed a treaty with Hitler to make Roman Catholicism the official church of the Third Reich, something it would rather we forgot about.

In terms of decades, the Vatican’s responses to films in the 1940s and 50s often exposed its attempts to distance itself from its alliance with the Nazi regime. Not particularly in horror, but in Italian cinema on the whole (the neorealism movement dealt very much with the plight of the working classes under fascism). In the 1960s and 1970s, it became clear that the Vatican was concerned that a great shift was happening. Following the Vatican’s attempts to modernise itself, there was a mass apostasy with millions of Catholics breaking away from the church. Thus, any film that presented criticism of the church (valid or otherwise) represented a problem, one that the Vatican did its best to crack down on. Subsequently, a number of directors found themselves in court, tried under blasphemy laws, because of the content of their movies.

Were there any films that the Vatican condemned with unusual severity or, conversely, any that you were surprised they overlooked?

Yes! One thing I’ve learned is that the Vatican is far more concerned with any criticism of the Church itself, and its past crimes, than it is of any actual blasphemy or sacrilege. Take a film like Ken Russell’s The Devils, which had a 2 page pastoral review in the Segnalazioni Cinematografiche damning every single aspect of the movie because of its “licentious portrayal of history”, or Salo by Pier Paolo Pasolini, which as well as being an extreme, gross-out movie, functions as a condemnation of Fascism and the alliance between the Church and the Reich, and the Vatican invited four journalists from Catholic newspapers, as well as their in house critic, to pass comment on it. By contrast, something like Lucio Fulci’s City of the Living Dead, which begins with a Priest committing suicide that brings about the biblical apocalypse and is clearly commenting on the Church’s attitude towards suicide and is attempting to portray the biblical rapture, the death of God and the rise of the underworld (so is a sacrilege from start to finish), the Vatican’s reponse was only one short paragraph, not even 100 words. They still condemned it, but mostly for its gross-out gore sequences.

Your book highlights the cultural and historical tensions between the Vatican and horror. Do you think this conflict has shaped the trajectory of the genre itself?

It has indeed, particularly in Roman Catholic countries such as Italy, Spain, France and the US (and the UK, even though technically our official church is Anglican). Directors in Italy and Spain have been particularly mischevious and like to indulge in various transgressions to get a reaction. The zombie filone became very different in Europe, taking limited influence from the Romero classics and instead using the zombie theme as a perverse notion of the resurrection, where instead of the sould excreting the body and going to heaven, the body excretes the soul and visits hell upon the earth.

When William Friedkin’s The Exorcist actually was praised by the Vatican for its portrayal of heroic priest doing battle with (and defeating) Satan’s minions, there was an explosion of Satanic Horror films from across Europe, the UK and US, and it was interesting to see which ones the Vatican liked and which ones it didn’t.

Given the Vatican’s history of censorship, do you see parallels between their influence on cinema and modern attempts at suppressing or reframing horror narratives?

I tend to talk a lot about the Video Nasties controversy in the UK in the early 1980s, where 72 horror and exploitation films were banned from home video release and, in roughly 50% of cases, their distributors were successfully prosecuted under obscenity laws. The initial architect of the campaign was Mary Whitehouse, an evangelical Christian who sought to use her censorship campaigns to spearhead a Christian revivalist movement. Because she had the ear of conservative MP Graham Bright, she was able to convince him to bring a Bill to the House of Parliament that became the Video Recordings Act. In addition, the prosecutions of films were brought about at a local level, by town and city councils and petitioned for by their local censor boards. To give you an idea of the makeup of some of these boards, my home town of Rochdale had a town censor board that featured councillors, the priest from our Catholic Dioscese church and a couple of parishioners, one of whom was my grandma! So the Catholics contributed heavily towards that era of extreme censorship.

You have a background in health research, how, if at all, does that inform your approach to horror, particularly regarding its psychological and societal impact?

I’ve worked for the Health Research Authority (the governing body for all health & social care research in the UK) for ten years. My professional background definitely informs the way I write. I tackle my subjects the same way I would expect a health researcher to tackle their studies, in that I need a clear and defined primary question to answer, for example “Does the Vatican attempt to censor the horror genre, and does it do so more than it does other genres of film?”. My approach is then to try to disprove the hypothesis behind the question, which is a scientific approach that a lot of people still don’t seem to understand. Some fans, critics and writers (and the general public) just search for evidence that backs up their original opinion or hypothesis and that’s how bias happens. By only searching for evidence that you are correct, you are instantly ruling out the idea that you might be wrong, whereas if you’re searching for evidence that you are wrong and uncover mostly information to the contrary, that’s how you begin to strengthen your position. From there I move to secondary, more open ended questions such as “Why does the Vatican condemn certain subgenres more than others?” and “What, if any, are the sociopolitical contexts behind its condemnation of certain films or subgenres?” I continue to research until I’ve reached data saturation point (where the information is starting to become homogenous and its clear that you aren’t going to learn anything new) and I prefer to have my writing peer-reviewed wherever possible.

Another thing that shapes my writing is ensuring the right voices are involved. There’s an ethos of staying in your lane, for instance you wouldn’t want to see white writers tackling the themes and subtexts of Black horror, or cishet writers tackling those of Queer horror, and rightly so – to a point. For my third book, which I am currently drafting, I wanted to explore how horror reflects certain experiences in different countries around the world, which caused some ethical issues for me – I’m not qualified, for instance, to discuss the First Nations’ experience in countries such as the United States or Australia, but I’ve always been fascinated by the subject. So I will only write about issues such as this if I can consult the people whose experiences and voices truly matter, and use my platform to lift them, rather than myself. That’s why, for my third book, I am consulting with groups of relevant people (like the above example, but there are several others) and their considerations will inform everything I write. If it isn’t important to them, it simply doesn’t go in. “Nothing about me, without me” is a principle I carry forward from health & social care research. My organisation has done a lot of work to create principles of public involvement that ensure a diversity of viewpoints, and I use those principles in my approach to writing.

Italian genre film is one of your specialties. How does the Vatican’s influence on Italian cinema compare to its role in horror censorship more broadly?

As I mentioned in my response to an earlier question, the Vatican’s role in horror censorship would not have come about if it weren’t for its desire to control the environment at home in Italy. Italy was one of the first countries to have a cinematic movement: the second feature length film ever made, worldwide, was Italian, Horror and Catholic (it was a 1911 adaptation of Dante’s Inferno). Unfortunately, because of fascism, Italian cinema was effectively shut down for several decades, and only grew to prominence in the mid 1940s after Mussolini was deposed and executed. As Italians saw an opportunity to properly discuss and reflect upon their lives under fascism, the Vatican saw an opportunity for censorship. When Italy’s horror genre began to form again in the late 1950s, the Vatican sought to stamp it out immediately. This then informed its opposition to horror films from around the world, as the church recognised that foreign horror products would influence Italy’s own filmmakers and its populace.

Was there a particular horror film that first sparked your interest in the genre, and has your perspective on it changed in light of your research?

The first horror films I saw were video nasties. While my nan was a censor, my dad was a VHS pirate, so when she had copies of these films to review and pass verdict on, he would make sneaky copies of them and distribute them around our area. I used to sneak downstairs at night and I remember watching a bunch, but the ones that stood out were Lucio Fulci’s horrors. Zombie Flesh Eaters, City of the Living Dead, The Beyond, House by the Cemetery. I loved them, but it wasn’t until decades later, as an adult, that i realised they were inherently Catholic films. Once I tied the two together, that gave me the inspiration for my research, but it was through my research that I realised just how much Catholicism has informed so many horror films. Even when there is no overt Catholic element, there’s usually some Catholic subtext in there.

Given the Vatican’s historical role as a moral gatekeeper, do you believe modern horror is still pushing back against religious institutions, or has that conflict evolved into something else?

Thankfully, the Vatican’s influence has waned over the years. Back in the 40s, 50s and 60s, the judgments of the Segnalazioni Cinematografiche could make or break a film in Italy. Because over 90% of the population were Catholics, that meant that there was a good chance your local cinema owner or projectionist were Catholics, so if the church forbade a film, it wouldn’t even get screened. As the years rolled on and the secularization of Italy crept in, people took less and less notice of the Vatican and watched whatever interested them. I don’t think the Segnalazioni Cinematografiche is even published any more – the most recent one I’ve found was from 2009. So basically, there’s nothing to push back on any more. Horror won the war!

What do you see as the future of religious horror, will it continue to challenge institutions like the Vatican, or has the genre moved on to newer ideological battlegrounds?

I think horror will always utilize religion, and particularly Catholic imagery and symbolism, because its such fertile ground and also because almost 20% of the world’s population are Catholic (if you expand to include all Christians, they make up 33%, a third of the entire population of the world, so that’s a massive target market). That said, there’s no real need to challenge the Vatican as an institution any more because it has relatively little actual power these days. The current horror landscape certainly seems to be more concerned with challenging political positions, as political populism is a genuine threat to the world right now, seen with Trump and the MAGA movement that is breeding fascism in the US, Boris Johnson and Nigel Farage in the UK, and Giorgia Meloni in Italy. These are the battles horror needs to fight right now (despite what a certain clown franchise director would have us believe based on their recent comments).

Matt Rogerson is a Manchester-based film critic and health researcher. A PAGE International Screenwriting Awards finalist, he has written for Diabolique Magazine, Dread Central, Horror Homeroom, and Horrified Magazine. His work focuses on horror history, censorship, and the intersection of religion and cinema. Rogerson will be speaking on Faith, Apostasy and Lucio Fulci at Miskatonic Institute of Horror Studies in London, UK on the 8th of April. Find tickets here!

Leave a comment