By Cullen Wade

The monster movie turns 100 this year.

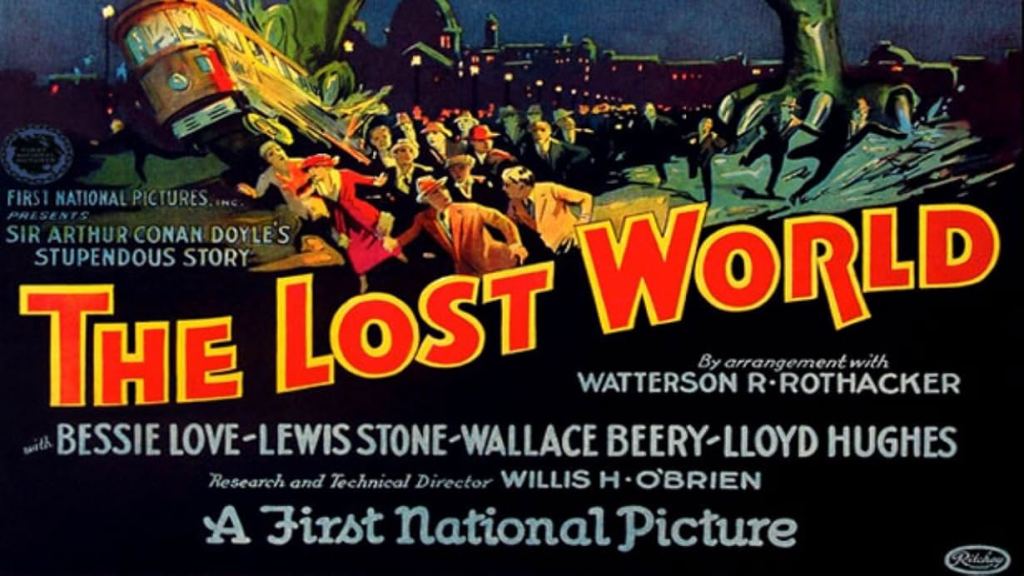

It’s not the first film to feature a monster, nor the first to depict a city-smashing beast, but Harry O. Hoyt’s The Lost World (1925) was the first feature-length, action-packed, SFX-heavy, live-action creature feature. It inspired King Kong, which inspired Ray Harryhausen, who inspired, well, everybody. And in choosing to write about it for its three-digit birthday, I have to figure out how to approach a movie dating from the Calvin Coolidge administration.

Many people say my job as a critic is to assess everything in its proper historical context. I should avoid imposing the values, standards, or politics of the present on art from the past. To do that, they say, would be to commit a fallacy called “presentism.”

If they’re right, I guess I’ll have to own being a bad critic, because (a) I don’t know how to see through any other eyes than my own, right now; (b) I’m not sure that’s possible for anyone; and (c) even if I could, I wouldn’t want to. I’d be leaving too much of value on the table.

I’ll explain what I mean, but first the plot. Ed (Lloyd Hughes) is a young journalist whose girlfriend won’t marry him until he’s done something dangerous. Enter Professor Challenger (Wallace Beery), an anthropologist just back from the Amazon with tales of a remote plateau where a population of dinosaurs seems to have dodged extinction. With his colleague still trapped there, Challenger hopes to mount a rescue expedition—and bring back some proof so he won’t get laughed out of the halls of academia. Ed volunteers for the party, which includes another professor, an explorer named Roxton (Lewis Stone) the missing scientist’s daughter Paula (Bessie Love), two manservants, and a monkey. Arriving at the volcanic plateau, the group finds that Challenger’s claims are true. The bad news: Paula’s dad didn’t make it. The worse news: their only way off the plateau has been dismantled by a playful pteranodon. Caught between rampaging dinosaurs, a stalking ape-man, and an imminent volcanic eruption, the group must find a way to escape the plateau.

Presentist Lens #1: Representation

I won’t beat around the bush: one of the servants is played by a white actor in blackface, and his speech cards are written in parodic, minstrel-style dialect. The well-actuallys of the world will say, “That’s the way things were back then, just accept it.” This attitude poses several problems. First, it assumes my objection to blackface is purely intellectual. Those oh-so-enlightened rationalists don’t seem to appreciate that no amount of “acceptance” can stop my stomach from turning upon seeing the legacy of minstrelsy paraded around.

Second, the reification inherent in “that’s how things were” erases the many, many people who thought it was bullshit even back then. Susan Gray and Bestor Cram’s 2017 documentary Birth of a Movement tells the story of journalist William Monroe Trotter, who led the fight against the KKK-glorifying Birth of a Nation in 1915. The historical relativism argument dismisses the brave work of people like Trotter, and is far too forgiving of the ones, of any given era, who knew they were on the wrong side of history. Which, I suspect, is the true agenda of such rhetoric.

It’s a shame, too, because the character, whose name is “Zambo”—you cannot make this stuff up—could have been written respectfully. He is smarter than the white butler he’s paired up with, and he devises a plan to rescue our stranded heroes from the mountain with a rope ladder delivered by a monkey. By merely casting a Black actor, and reworking the dialogue a bit, they might have created a character we could uphold today as an example of decent representation.

The Lost World fares better when it comes to gender politics, despite not getting off to a great start. Gladys (Alma Bennett), Ed’s beloved at the film’s start, insists that she will not marry him until he has proven himself an intrepid adventurer, and promises to wait for his return. While abroad, Ed falls in love with Paula, but reluctantly keeps his promise to Gladys. Upon returning, Ed finds that Gladys has already married a wealthy dandy who’s never left England.

Gladys’s stereotyping as a fickle, superficial woman is counterbalanced by Paula’s rather more complex characterization. Bessie Love as Paula does the film’s heavy lifting acting-wise, showing pluck in the face of danger and delicate tact when navigating a tricky love quadrangle. The much older Roxton is in love with her, and Paula neither ridicules nor encourages him. Instead, she manages to set clear boundaries while preserving his feelings. For better or worse, their age difference is never made a factor.

Though she falls for Ed over the course of the adventure, and agrees to marry him when it appears they’ll never make it back to England, as soon as they’re rescued Paula reminds Ed of his commitment to Gladys. Ed looks like he’s about to press the issue, but she literally dodges his kiss. Ed respects her boundary, which makes their reunion, upon learning of Gladys’s inconstancy, feel earned and appropriate.

If we can agree that The Lost World is better on gender than it is on race, a glance at the credits gives us a possible reason. The film’s screenplay (or “scenario,” in 1920s parlance) was written by Marion Fairfax, a former stage actress turned playwright who parlayed Broadway success into a fruitful film career and ran her own Hollywood production company.

Visibility does not necessarily equal empowerment. It’s impossible to know if a female screenwriter accounts for The Lost World’s nuanced treatment of its women (though the corresponding character to Paula in the 1960 version, written by a man, is far less dynamic), nor whether the involvement of a Black creative would have corrected some of the film’s racism. But we wouldn’t even be asking the question if we limited our reading to some incomplete notion of “the standards of its time.”

Presentist Lens #2: Influence

If your experience of silent films involves a lot of stiff dudes standing around emoting, you might be blindsided by the onslaught of dino dueling, ape-man brawling, lava-spewing, masonry-smashing, cliffhanging adventure The Lost World has in store for you. The film’s pacing feels modern and makes other 1920s monster movies seem glacial by comparison. European filmmakers fleeing fascism hadn’t yet brought their moody expressionism to Hollywood—this is pure American pulp, breathlessly racing itself to the next setpiece.

Nowadays, it’s obvious why we can see tropes from this movie in everything from Creature from the Black Lagoon and Land of the Lost to the Indiana Jones and Jurassic Park franchises and even Pixar’s Up, not to mention the whole of the kaiju genre up to and including the current slate of Monsterverse films by Legendary Pictures (especially 2024’s Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire). The Lost World, after all, is the creator of those film tropes. But the moviegoers of a century ago would have seen it differently. Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1912 source novel lent its name to a subgenre of fantasy fiction that was further developed by pulp authors like Edgar Rice Burroughs, A. Merritt, and H.P. Lovecraft. By the time this film was made, the tropes of the lost world subgenre were already well established.To 1925’s audiences, The Lost World’s pacing might have seemed strange, and its plotting stale, relative to what they knew. Now that audiovisual media have replaced the written word as the main form of cultural production, the literary origins of its tropes matter less than the first time they were deployed onscreen. Only through presentism can we appreciate The Lost World as a forward-thinking innovator rather than a predictable, breakneck adaptation of a popular novel. It’s one of the few films from the silent era that a modern viewer can enjoy, not as a historical curiosity, but as a cracking adventure yarn.

Presentist Lens #3: Special Effects

If there’s any area where today’s perspective does us no favors, it has to be visual effects, right? Today’s cutting-edge digital sorcery makes this film’s jerky stop-motion and miniature work look like a kid playing with action figures. Surely this is one realm where “good for its time” isn’t damning with faint praise?

Well, at some point in the last century, we decided that movie special effects’ objective was to be as true to life as possible, making yesterday’s hotness perennial losers in the ongoing photorealism arms race. But that was not a foregone conclusion. Black and white films have it easier in this regard, as the monochrome image’s inherent unreality frees them to be more abstract. Now that we know dinosaurs likely looked nothing like what The Lost World depicts, we can view the film more as fantasy than science fiction and appreciate its artistry free of verisimilitude’s shackles.

What’s more, as a presentist, I think photorealism is on the way out. Soon, there will be generative AI tools that can spin up a video clip of anything you can imagine with perfect photoreal fidelity. Most people do not want this. We want our art to have the touch of a human hand. Soon we will seek out art that is imperfect, proof that it was made by someone with a soul. Ironically, the artificial will become a hallmark of authenticity.

The Lost World’s visuals vibrate with the care of a human artist. Stop-motion animator Willis O’Brien changed the game with this film. He combines miniatures and moving mattes to create the sequence that launched a thousand kaiju: a dinosaur stomping through contemporary London. The street-level view of the creature’s lunging head, barely visible through the dust and smoke of its own rampage, anticipates the subjective camerawork that helped the kaiju genre convey its monsters’ terrifying scale.

But it’s not just creature effects that give The Lost World its visual majesty. Of all the gorgeous matte work (by an uncredited artist) the most memorable is a wide shot of the sheer plateau, rising from the jungle floor like a storybook stronghold. The recent 102-minute Flicker Alley release uses tinted frames, based on recently unearthed footage, to give each section its own personality. Vibrant amber for bustling London, blue for its nighted streets, green for the jungle, fire red for the volcano, violet for the cooldown. Even a simple shot of a sunrise through palm trees is rendered gently transcendent in dusty mustard by effects cinematographer J. Deveraux Jennings.

Visually, The Lost World blends several techniques for enchanting the moving image into a captivating whole. We can honestly call it “good for its time,” as long as we acknowledge that its time is now.

Aaron Christensen, a.k.a. “Dr. A.C.”, is fond of saying that, just as you can’t step in the same river twice, you can’t watch the same film twice. I am a different person than I was yesterday, and everything that exists, regardless of age, exists in the present tense. The Lost World is in the public domain, viewable for free on The Internet Archive and YouTube. Assorted cuts and restorations are available on at least a dozen commercial streaming platforms. You can even watch it in full on Wikipedia. The film is more accessible today than ever before. The response of someone who discovers it tomorrow will be just as valid as somebody’s from a century ago.

The Lost World is a fun watch, brisk if a bit pulpy, with sumptuous visuals and special effects full of personality, albeit a little rough around the edges. It’s terrible on race and better on gender, perhaps thanks to a woman in an above-the-line creative role. It’s not the first film to earn that description, and it won’t be the last—historical relativism or otherwise. The Lost World isn’t fossilized. Why should our appreciation be?

Leave a comment