By Mo Moshaty

When my youngest told me they were certain to go to college, the pride I felt was almost immediately shadowed by something harder to admit: fear.

Not the fear of bad grades, or the fear of a messy dorm room, or even the usual loneliness of leaving home, but something much more sinister. I’m worried about the other students and the faculty. About the psychological power young adults hold over each other in institutions like this, and the pressure to belong, and the risks that don’t come from coursework, but cruelty.

I’ve had my own experiences with higher education, and you can read into that here.

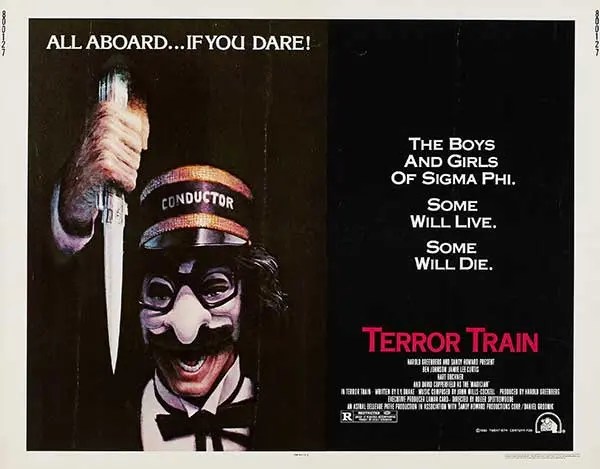

Watching Terror Train (1980) again, those fears came rushing to the surface.

At the heart of Terror Train is a prank, the kind of hazing ritual that’s too often dismissed as “just tradition.”

On paper, Terror Train is a classic early 80s slasher. A mass killer picks off students one by one during the New Year’s Eve costume party on a moving train. Under the surface, it tells a much darker, much more personal and much more relatable story. One that’s less about the killer in disguise and more about how a single moment of cruelty, shrugged off by the privileged, derailed someone’s life forever.

A fraternity of pre-Med students sets up a cruel trick on a timid pledge, Kenny (Derek McKinnon), with the help of Alana, played by Jamie Lee Curtis, they lure him into an intimate situation designed to humiliate him. It works all too well. Kenny suffers a severe psychological break and is institutionalized. The break becomes nothing more than a footnote for the others, a bad memory, something they imagined everyone will eventually get over. But Kenny doesn’t “get over it” because hazing isn’t about bonding. It’s about establishing who has social control and who’s desperate enough to accept anything just to belong.

When I think about my own child stepping into college life, I don’t worry they’ll fail a class so much as I worry that they’ll trusts the wrong person. I worry that they’ll find themselves surrounded by a culture that normalizes humiliation, danger, roughness, and violence as the price of entry. Terror Train doesn’t just use hazing as a plot device, it shows us its aftermath. It shows that the people at the center of the “joke” don’t always walk away laughing.

What’s striking is how easily the students move on from what they’ve done. By the time the main events of Terror Train unfold, they’re graduating, and they’re launching careers and celebrating futures in medicine. Their cruelty has been safely tucked away and forgotten like an old yearbook. For me, this is one of the sharpest critiques that’s baked into the film.

It’s a stark look at how privilege erases the consequences, not for everyone, but for those who already stand atop of the right social letters. All the right moves, all the right faces. Nobody at the medical school seems to have held them accountable. No expulsion, no charges, no black marks on their records, no reprimand of any kind. Kenny is institutionalized, and the others get degrees and bright futures. It’s an uncomfortable truth that Terror Train lays bare: elite institutions often protect their own, not the people they’ve harmed or made feel uncomfortable or those who’ve had to fight back as a result of reactive abuse. It’s easier to celebrate success stories than to admit they’re sometimes built on someone else’s suffering.

And I think about the pressure students face to perform. To network, to succeed academically and through sports and even socially with the amount of club after club after club after community service that these kids have to go through, I can’t help but worry. How often are young people asked to forget their humanity just to get ahead?

In most slasher films, the killer is either pure evil, an unstoppable force, or a deranged anomaly. But Terror Train does something quieter and far more disturbing. It shows us that Kenny, the eventual killer, wasn’t born monstrous. He was made monstrous through cruelty, humiliation, abandonment, and institutional neglect. When the prank shatters Kenny’s mental health, the others simply, and blithely, move on. Their futures are intact. Kennys is wrecked. No apology, no restitution, just erasure. In that way, Terror Train isn’t about a vengeful spirit haunting a party, it’s about what happens when society chooses to forget the wounded. This doesn’t excuse Kenny’s later violence AT ALL, by any means, Highlight it CAPS LOCK, but it reframes it rather than seeing his actions as random.

The film invites the harder question: how much responsibility belongs to those who inflicted the original wound? It becomes clear that Kenny is not a natural villain. He’s a product of trauma left untreated, of institutions that cared more about protecting reputations than protecting people.

The Kenny archetype: a young person profoundly harmed by peers or systems then left to spiral, is not a work of fiction. History offers chilling real-world parallels where ignored trauma has led to catastrophic results.

In 2010, Phoebe Prince, a 15-year-old student in Massachusetts, was relentlessly bullied at her high school. Students tormented her both online and in person. Despite visible signs of distress, the school administration failed to intervene effectively. Phoebe died by suicide after months of harassment, and this tragedy not only exposed individual cruelty but institutional failure. Teachers and administrators knew about the bullying but chose inaction and chose to minimize the severity of what was happening to Phoebe until it was too late.

That same year, Tyler Clementi, a freshman at Rutgers, died by suicide after two fellow students secretly streamed footage of him in an intimate encounter. Despite policies meant to protect students, Tyler humiliation went viral. The university’s slow and bureaucratic response: treating the situation like a minor conduct issue, rather than a catastrophic breach of trust, highlighted how institutions often prioritize procedure over human urgency.

I’m gonna take a quick segue, here. While this isn’t a case of bullying leading directly to violence, The Stanford Prison Experiment remains one of the most infamous demonstrations of how quickly ordinary people, especially young adults and peer groups, can inflict harm when systems encourage dominance. The participants who were assigned to be “guards” began psychologically torturing those assigned to be “prisoners” within days. The experiment, designed by psychologist Philip Zimbardo, had to be shut down early because the abuse escalated so rapidly.

Phoebe’s death was not simply the result of a few bad apples. It was the consequence of an entire ecosystem that allowed cruelty to thrive unchecked. The public exposure, shame and isolation all played roles in pushing Tyler beyond the brink. The students who humiliated him likely thought this was “just a prank”, never fully understanding the gravity of the harm they unleashed. The Stanford Prison Experiment shows how easy it is for “good” or “normal” students those destined for prestigious futures to commit severe harm when institutional oversight fails or actively encourages dehumanization.

In all of these cases, and Kenny’s fictional story, the pattern is disquietingly consistent.

• A vulnerable individual is isolated, humiliated, or traumatized.

• Institutions such as schools, universities or administrators, minimize or ignore the warning signs.

• The perpetrators feel no real consequences.

• The victim was left to carry the psychological wreckage by themselves.

Eventually, that unattended trauma explodes, sometimes outwardly, sometimes inwardly. Psychologist Jennifer Freyd coined the term “institutional betrayal” to describe this phenomenon: when institutions people depend on for protection, harm them instead.

Terror Train doesn’t have to spell this out directly. It’s in the subtext, the lingering shots of the revelers, still drunk, still untitled, so absolutely blind to what they’ve done, board a train, hurtling inevitably toward disaster. Kenny’s transformation from frightened pledge to avenging killer is not a sudden flip of the switch. It’s a slow, cumulative collapse, a ghost story born not from death but from deliberate burying.

Perhaps the most devastating illusion, the students aboard the train believe, is that Kenny should have gotten over it. That whatever they did, however cruel, was temporary and in time Kenny would magically heal themselves. But real life tells us otherwise: trauma, especially humiliation-based trauma, during youth, doesn’t simply evaporate. When unaddressed, it festers. It reshapes self-perception, it reconfigures trust. It can curdle into hopelessness, rage, and even violence against self and others. This is why the villain origin story in Terror Train hits me so differently, especially now. It demands that we ask not just who the killer is, but what made him?

The tragedy at the heart of Terror Train feels oddly current because the systems that failed Kenny are still failing students today. Despite public awareness, college campuses remained fertile ground for hazing, bullying, social power imbalances, and unchecked trauma, especially among the most prestigious or affluent. Institutions where reputation often outweighs accountability.

So are anti-hazing policies progress are just a PR stunt?

In response to repeated scandals, some fatal, universities across the United States and internationally have enacted strict anti-hazing policies. Many require new students to attend. Educational seminars on consent, respect, and bystander intervention. Some institutions have even banned fraternities, sports teams or clubs implicated in hazing practices. And yet, despite these reforms, hazing deaths and abuses still occur every year. According to research by Hank Newer, a leading hazing expert, at least one hazing related death has occurred every year since 1959. The problem isn’t just the existence (or lack) of rules, it’s the culture beneath them.

Too often, hazing is seen as not a danger, but as a right of college passage. Victims are encouraged to toughen up, to rush. Perpetrators are shielded by secrecy and loyalty, legacy, and the institution’s sphere of scandal. Just like in Terror Train, the institution’s priority is often protecting its image, not protecting the vulnerable.

I really want to talk about the psychological power students have over each other. In the enclosed high pressure ecosystem of college life, social dynamics intensify dramatically. One student’s opinion can determine and others belonging. A whispered rumor, a cruel prank or public embarrassment can devastate someone’s mental health, especially when away from family familiar structures and emotional support.

Modern psychology shows that:

• Social rejection activates the same brain regions as physical pain. (Eisenberg, 2012).

• Youth are practically vulnerable to peer influence because the prefrontal cortex, which governs impulse control and risk assessment, is still developing into the mid-20s.

• Humiliation can create complex trauma, similar to prolonged abuse when betrayal, isolation and shame are combined.

Long story short, students have enormous psychological power over each other, often without realizing it. Or worse, some realize it and wield it intentionally.

So what’s the institutional blind spot here, and who actually gets protected?

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, we all know, and research does show us that affluent, predominantly white, prestigious institutions (like the fictional medical school in Terror Train) often foster environments where the “best and brightest” are shielded from consequences. Think, Promising Young Woman. When students are seen primarily as future doctors, lawyers or leaders, there’s a dangerous temptation to minimize their wrongdoings as youthful mistakes rather than serious ethical failures.

“He’s just a kid,” even though he’s 24.

This protection fuels the cycle of minor abuses being overlooked, putting a time limit on the victims suffering and the ability for the abuser to have that harm perpetrated, unchecked because it will be silenced by perceived potential and success.

In Terror Train, the graduates celebrating on the train represent this willful amnesia. We’re successful now, what we did back then doesn’t matter, we were just kids. But the trauma doesn’t vanish. It waits, and sometimes in returns in ways no one can predict.

Circling Back to my fear-

For any parent, particularly those sending a child into the closed world of college, this raises profound fears.

Will my child be safe? Will they be protected if something happens? Will they know how much power they hold over others and wield it with compassion and not cruelty?

The worry isn’t just about what a child might experience, it’s about what they might witness and do in group dynamics where cruelty is normalized. Because the truth is, every student has the capacity to be a Kenny, a bystander or perpetrator, depending on the culture they’re immersed in.

Modern mental health services on campuses are crucial steps forward, but they are not enough without the entire cultural shift. Coming from secrecy to transparency, from lenient punishment to prevention, from image management to humanitarianism. Terror Train ends with the past crashing back into the present because the pass was never truly gone to begin with. It was ignored, buried, and left to rot until it exploded. And that’s the real horror the film points to: when we fail to acknowledge the traumas we create in our institutions, in our communities, and within our children, they don’t just disappear, they transform.

Leave a comment