By Rebecca Sayce

Becoming a parent is one of the most significant physical and mental shifts a person can experience, and though a bouncing bundle of joy is a blessing, the strain it can cause on our health is tremendous. Mental Health Foundation reports that approximately 68% of women and 57% of men with mental health problems are parents. The World Health Organisation states that worldwide, about 10% of pregnant women and 13% of women who have just given birth experience a mental disorder, primarily depression. For those who suffer from preexisting mental health conditions, the strain of a dependent can exacerbate these issues and have long-lasting effects on both the parents and the child. A study from Cardiff University found that children living with someone who has mental health issues were 63% more likely to experience mental health difficulties at some point in their lifetime, perpetuating a cycle of mental health struggles across generations.

Generational trauma and a protagonist’s endeavour to break the chain have been a focus of horror films for decades, notably increasing through the 2010s and 2020s as our knowledge around mental health issues, particularly perinatal and postpartum mental health, has become more nuanced. Often, we see this struggle portrayed through mother-daughter relationships and the possibility of the next generation of mothers continuing the cycle of deteriorating mental health. It somewhat villainises mental health issues and the struggles faced by parents, with the end goal of the protagonist to escape their ‘doom’ by cutting ties with their mother, or worse. Though more often than not, horror films focusing on maternal mental health do not see the child triumph, instead falling to the same illness or dying in the process of escaping the family unit.

Adapted from Stephen King’s novel of the same name, 1976 film Carrie tells the story of the titular teenager (played by Sissy Spacek) as she faces torment not only from her classmates, but her religious fanatic mother Margaret (Piper Laurie). Strange phenomena begin to happen around Carrie, which leads her to believe she has supernatural powers, which become too much for her to handle when the night of her prom goes drastically wrong. Margaret’s mental illness is shown through religious fanaticism and the belief that Carrie is possessed by the devil. Because of this, Margaret is physically and emotionally abusive towards her daughter, controlling Carrie to the point her sexuality and anger are completely repressed, manifesting as telekinetic powers when she begins menstruating for the first time.

Margaret views almost everything as ‘sinful’, especially when it comes to her daughter, female anatomy, and sexuality. It is later alluded to that Margaret’s trauma around sexuality stems from Carrie’s father assaulting her, another trope common in horror films exploring mother-daughter relationships in which the root cause of the mother’s trauma stems from the father. When considering that children can be at a heightened risk of mental health issues when a parent struggles themselves, in Carrie, we see the effects of Margaret’s outbursts and strict control cause her daughter to be increasingly isolated among her peers, leading to intense bullying. Rather than breaking the cycle, Carrie’s rage overcomes her during the prom when she is covered in pig’s blood by her classmates, causing her anger to bubble over and inadvertently burn down the hall with those who mocked her inside. It can be seen that Margaret’s mental illness fuelled her abusive behaviour towards Carrie, denying her agency and restricting her life to the point she exploded, ruining both of their lives in the process. In its portrayal of maternal mental illness, Carrie shows Margaret solely as monstrous; a manipulative and controlling character facilitating an unhealthy and abusive environment to parent her child, who must resort to violence to escape.

Much like Carrie, David Cronenberg’s gooey body horror The Brood features maternal antagonist Nola (Samantha Eggar), a severely disturbed woman undergoing a messy separation from her estranged husband Frank (Art Hindle) and embroiled in a custody battle for their five-year-old daughter Candice (Cindy Hinds). Nola is undergoing ‘psychoplasmic’ therapy with Dr Hal Raglan (Oliver Reed), encouraging patients to let go of their suppressed emotions through physical changes to their body, separating from the trauma. But Nola’s rage is too great, leading her to psychoplasmically create an external womb that parthenogenetically births a brood of mutated children that kill based on Nola’s therapy sessions.

From the outset of the film, the effect of Nola’s mental health issues on Candice is apparent. She has been returned to Frank’s custody with scratches and bruises on her body, leading her father to consider cutting contact between the mother and daughter. Throughout The Brood, Candice is a sitting duck for the abuse of her mother, both directly and indirectly. Though the creatures do not directly harm Candice, they kill those around her, and she bears witness to two murders. Like Carrie, Candice begins to withdraw socially from her peers and becomes increasingly isolated as a result of her mother’s behaviour and her parents’ divorce. In her sessions, it is revealed that Nola was neglected by her father and physically and verbally abused by her alcoholic mother, but despite the trauma it caused, she continued the cycle by replicating their actions towards her child. Though we don’t see Candice replicate this pattern of behaviour, the brood born from Nola does, killing the subjects of her therapy sessions with Dr Raglan and perpetuating further trauma as a result of Nola’s own experiences, which stem from her parents before her.

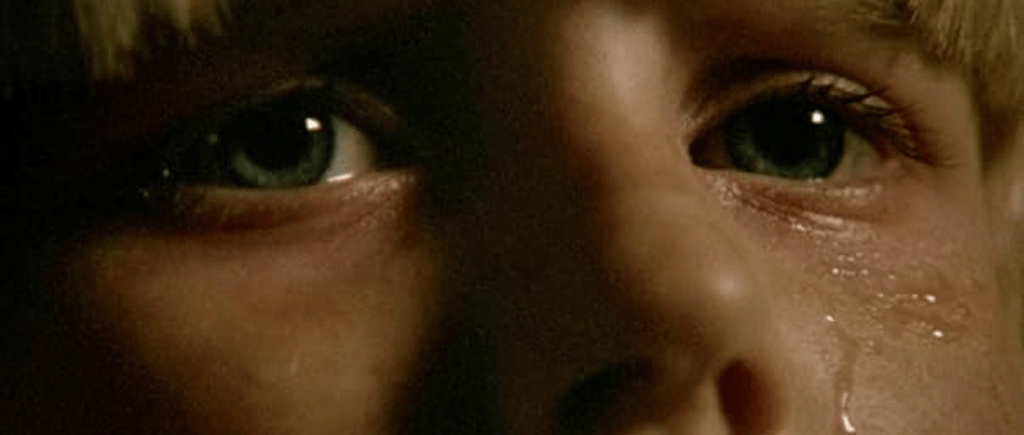

Candice is saved from her mother’s destruction when Frank strangles Nola to death, severing the connection between her and the brood. But the mental damage done to Candice is evident as she is carried away by her father, with terror etched into her face. The final scene sees lesions growing on Candice’s body similar to the early stages of change patients experience undergoing psychoplasmic therapy, suggesting that the cycle of trauma will tragically continue through a third generation. Nola chose to attempt to kill her child rather than be without her, with Cronenberg highlighting the extremes that stress and trauma can push parental figures to, with terrifying consequences. If we consider the brood children of Nola, like Carrie, The Brood sees the mental health of the mother lead to the destruction of the child, rather than their escape. The creatures can also be seen as a manifestation of Nola reliving her trauma day in, day out, at the expense of both her own sanity and that of others.

In the 1970s, there was a significant shift in how women’s mental health issues were discussed, with the women’s liberation movement changing attitudes towards mental health conditions such as postnatal depression. A growing emphasis was placed on women’s mental well-being during and after childbirth, but that does not mean the topic wasn’t taboo. A stigma around mental health issues still remained, particularly when it pertained to mothers who were often seen as the primary caregivers to children. We can see this reflected in films such as Carrie and The Brood, highlighting societal fears of the pressures of motherhood and the effects of maternal mental health, leading to the breakdown of the familial unit and extreme harm coming to the children in these narratives. As five decades have passed, our understanding of mental health and access to support and treatment has grown exponentially, leading to more nuanced, sympathetic portrayals of maternal mental health issues reflected in their relationship with their daughters.

Adapted from David F. Sandberg’s 2013 short film of the same name, Lights Out was turned into a feature film in 2016, exploring the effects of generational mental illness through Sophie (Maria Bello) and her children, Rebecca (Teresa Palmer) and Martin (Gabriel Bateman). Sophie has suffered from mental health issues her entire life, which she can manage with therapy sessions and medication. Rebecca has distanced herself from her mother due to her erratic behaviour over the years and coldness toward her offspring, but when social services become involved with Martin when he begins falling asleep in classes, Rebecca returns home to uncover the mystery behind her mother’s behaviour. It becomes apparent that a malevolent entity, Diana (Alexander DiPersia), became attached to her mother when they met in a psychiatric facility as teenagers, feeding on the depression Sophie harbors. She can control Diana when she is mentally stable, but when Sophie’s husband, Paul, dies, she slips into darkness once more, and Diana takes hold, threatening the safety of those around Sophie who aim to keep them apart.

Taking inspiration from The Brood, Sophie’s mental health issues manifest as a being outside of herself. While Nola did not know what the brood were doing to those around her until the final act, Sophie is well aware of the dangers Diana poses and takes active steps to ensure her mental health, and therefore the entity, are kept under control, and her children are kept safe. In Lights Out, despite her distance over the years, Sophie is portrayed as a loving, doting mother who will put her children first at all times, even tragically taking her own life in the film’s final act to keep them safe from Diana. The ending has been criticised for its portrayal of suicide and the fact that Sophie’s death is somewhat painted as a positive to rid the world of Diana, but it highlights the tragic consequences of what can happen when mental health issues are not adequately supported and the devastation that can follow.

Rather than desperately trying to break free from her family, Lights Out begins with Rebecca already distancing herself from her mother and her issues, choosing to return to the family unit to care for Martin and understand Sophie’s demons. The effects Sophie’s mental health has had on her children is apparent, with their fractured relationship being the focus of the film from the off, but unlike Carrie and The Brood, Lights Out offers a sense of redemption in Sophie’s children coming to understand her struggles and empathise with their mother’s suffering at the hands of Diana, and therefore her depression. Rebecca’s character is portrayed with self-harm scars, suggesting she, too, has struggled with mental illness like her mother. But with the destruction of Diana in the film’s final act, it can be seen to represent the generational trauma ending with Sophie and both Rebecca and Martin going on to live their life without the looming spectre of mental illness. Despite its controversial depiction of suicide, Lights Out offers a more rounded look at a mother suffering from mental illness, separating Sophie the mother from her depression, manifesting as Diana, to showcase multiple aspects of her personality. Rather than severing ties with her children, which would lead to their destruction at the hands of her mental illness, Rebecca and Martin strive to better understand their mother’s struggles and destroy Diana, saving Sophie in the process. Sophie ultimately sacrifices herself to stop Diana from harming her children, representing the undying love a mother has for her children that allows her to stop at nothing to keep them safe.

Ari Aster’s 2018 hit Hereditary breaks the mold by having a narrative in which the mother, suffering from mental health issues, has died, with narratives focusing on the daughter navigating life while trying to better understand their parent. Hereditary begins with family matriarch Annie (Toni Collette) attending a grief support group following the death of her mother, Ellen. It becomes apparent they had a strained relationship, with Annie saying in her eulogy: ‘When her life was unpolluted, she could be the most loving person in the world,’ alluding to her secretive nature and troubled life. But Hereditary also delves into the mental health issues of Annie’s wider family, touching on her father’s psychotic depression and her brother’s schizophrenia as well as her mother’s dissociative identity disorder. In contrast to her relationship with her own mother, Annie is close to her daughter Charlie (Milly Shapiro), and her death while at a party with brother Peter (Alex Wolff) is the catalyst that sparks Annie’s falling apart.

With the constant flux of filmmaking and its tropes, as well as our understanding of mental health, representation onscreen is ever-changing. Horror films of the 1970s show us that maternal mental health was presented through the monstrous mother character, embodying the anxieties and pressures of motherhood. Carrie’s Margaret and The Brood’s Nola are undeniably antagonists within their respective narratives, causing physical and mental harm to their children Carrie and Candice as a byproduct of experiencing mental health issues and trauma. They can be seen to reflect the anxieties of the rising women’s liberation movement and a drive for more understanding towards women’s mental health issues, by showing two mothers experiencing mental strain, harming their children, and leading to the destruction of their family units. Moving into the 2010s and beyond, mothers experiencing mental health issues are less one-dimensional, monstrous characters and are instead given a depth that allows audiences to feel more sympathy towards them. Lights Out and Hereditary show central characters Sophie and Annie as complex human beings and loving mothers all the same despite their experiences with mental health issues. Their children, in extension, are seen as supportive toward their mothers and strive to understand their struggles and alleviate the issues they face. The narratives of these films challenge the expectations of motherhood and portray just how difficult it can be, especially when dealing with trauma and the terrifying prospect of repeating generational patterns when trying to raise your child. It shows that mothers often sacrifice a lot more than we realise in the name of love for their children, and without sufficient support, this can have devastating consequences.

Leave a comment