By Tori Potenza

Guys are all nonsense creatures. -Tomie

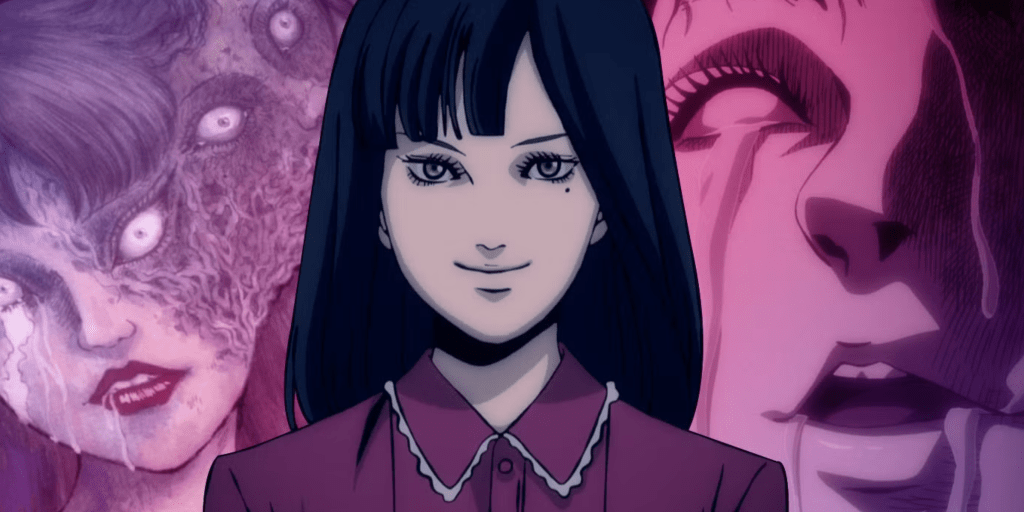

Junji Ito’s iconic character Tomie first appeared in the Japanese magazine Monthly Halloween in 1987. Since then, her stories have been compiled into various manga volumes, she has appeared in cartoon adaptations of Ito’s work, and has spurred on 9 movie adaptations, the first of which came out in 1998. She has become one of his most iconic characters. Tomie is a beautiful young woman who is adored by men; they become obsessed to the point where they murder her. But she always comes back and leaves havoc in her wake. In an interview with Junji Ito from 2019, he discusses her popularity, specifically with women, saying that she gets to be free and live a life that she wants, and that they wish they could be like her. Femme fans of horror have often found many monstrous feminine characters to sympathize with, so, unsurprisingly, Tomie is among them. Perhaps one of the reasons for this is that she does not try to fit into the mold that patriarchal values have enforced on women for centuries, and her presence, especially in the films, shines a light on issues around gender inequalities. And because she is a girl who can never die and always gets revenge on those who harmed her, she stands as the antithesis of the harmful “dead girl” trope that has permeated the media over the years. Her refusal to die and stay quiet is a constant reminder of the violence women are confronted with in a patriarchal society.

The “dead girl” trope is a popular trope in much of Western media. It follows an investigation of the murder of an idealized, beautiful young girl, whose death has a ripple effect throughout the community. Most commonly, she is popular, white, and full of promise. Laura Palmer in Twin Peaks is still one of the best examples of this. Her death is often tied to the shady underbelly of the town, and she is usually hiding secrets from those around her to maintain her status. These girls are often victims of systems that abuse women. And in their death, they become the equivalent of a mythological creature. In death, she is eternally beautiful. She will never age, gain weight, or have a wrinkle diminish her perfect face. She lives in memories, pictures, and stories, hiding the imperfections that made her human. Tomie, on the other hand, is almost too alive. And by coming back from the dead over and over, she makes sure that people cannot forget the violence enacted upon her. She gets to control her own narrative and get revenge on those who killed her, as well as those who acted as accomplices, and those who represent systems of power and control that want to keep her and other girls quiet, docile, and dead.

While Tomie is played by a different actress in each of the films, her look and personality remain more or less the same throughout. Most notably, she has long dark hair, a porcelain complexion, and a small beauty mark under her eye. While her outward appearance aligns with “yamato nadeshiko”, a term meaning the personification of the idealized Japanese woman, her personality is in stark contrast with this. The idealized woman “should” be subordinate, loyal, delicate, and graceful. While she may appear like this at first, those around her quickly realize that she is cruel, manipulative, and demanding. She often demands decadent food and expensive gifts from her suitors. She is also frequently unfaithful to her romantic partners. These men leave their girlfriends and go to extreme lengths to make Tomie belong to them, but the fact that she will never truly belong to anyone is one of the factors that drives them to the point of killing her. In a way, killing her is their attempt at having some ownership over her until she returns. Unlike the typical “dead girl” mystery, we often know who her killer is right away, and it is almost inconsequential who the murderer actually is. It could be any man, or even a woman, but anyone who is often upholding oppressive systems.

In her book The Monstrous-Feminine in Contemporary Japanese Popular Culture, Rachael Dumas discusses how, with Tomie’s return from the dead, she makes men, and even the women who uphold these societal values, confront their hypocrisies and the role that women are supposed to play in a patriarchal society. Tomie is so powerful because she “reflects long-standing anxieties centered on the female bodies and desires as threatening patriarchal structures while also elaborating intimate portraits of female suffering.” The fact that these men become obsessed with her because of her look alone reminds us of how much having an attractive appearance is valued under patriarchal rule. The men of these movies are often already involved in sexist behaviors before she shows up. She simply brings it out to an extreme. In Tomie: Rebirth, a group of friends meet at a restaurant to have a party. It is revealed that the party was put together entirely for the purpose of the men to find suitable girlfriends. The men complain to one another about how there are no attractive girls present. One of the friends even mentions that his friend got sick because of all the ugly girls. In most of the installments, her male targets are already in a relationship, which they abandon to chase after her. And people like doctors, teachers, artists, and much older men all prey upon her. These men all have the capacity to do terrible things; Tomie simply brings it out in them.

Women are not safe from Tomie either, but their relationships are often much more complex. But one of the things that their relationships reveal is that in many ways, women can be complicit in and actively help to uphold systems of oppression. In Tomie, the protagonist Tsukiko mentions how she is ‘not good with groups of girls’ and is portrayed more like a tomboy. It is revealed that when they were younger, Tomie stole Tsukiko’s boyfriend, and in turn, she blamed Tomie. She littered the school with pictures of Tomie that had “monster” written over them. Tomie comes back to force her to remember what she did to her former friend. Women are often seen as competition with one another, especially in the realm of relationships. And when it comes to infidelity, many blame the woman as opposed to the men who actually did the cheating. In Tomie: Replay, Yumi’s father goes missing, while trying to investigate his disappearance, she learns that he was having an affair with a nurse with whom she was very close. The mother reveals that she always knew about the affair, and the two simply accepted that this was their role to deal with, as opposed to leaving him. Tomie’s involvement in their lives ultimately unearths secrets that they tried to keep to themselves and forces them to confront them instead. And in Tomie: Another Face, Miki is a girl whose boyfriend left her for Tomie. She is heartbroken, but instead of being mad at him, she waits on the sidelines for something to happen. He kills Tomie, but when she returns, Miki becomes an accomplice and helps him kill her again to show her loyalty. Women are far too often left cleaning up the mess of men’s indiscretions.

When they become active participants in Tomie’s death, they find it like a bonding experience. This is what happens in Tomie: Re-birth when her suitor lives with his mother. He dotes on Tomie and does nothing for his mother. He will even belittle her and berate her for doing the wrong things. Tomie takes all semblance of power away from those she interacts with, making girls feel ugly and unlikable, and mothers feel meek and useless in front of their sons. They eventually kill her together. In that moment, the mother can take her rightful place once more and get to baby him, by showing him how to handle the situation by cutting up the body and cleaning up the crime scene. Even though they engaged in an ugly, brutal death, they feel a huge sense of relief at the status quo once again balancing out.

The other layer to these female friendships is the queer element that has a presence in several of the films. Even when in competition with one another, several of the girls still have something that draws them together. And in a culture that has trouble accepting queer relationships, sometimes being enemies fuels the passion. It is a fine line between love and hate. In the original Tomie, at the end, even after all the death and destruction, she and Tsukiko share a kiss by the water. Forbidden Fruit is the most overt in its sexual storyline, with the two often kissing and caressing each other. And in Tomie: Revenge, the girls are seen sleeping in the same bed, discussing how they don’t want to leave each other, and making plans for the future. And sometimes her friends become possessed by Tomie by interacting with her DNA and begin to exhibit some of the same traits. The later films go into how there can be Tomie duplicates out in the world (leading to films like Tomie v. Tomie where they duke it out to be the one and only. Perhaps these women becoming Tomie is a sign that they are freeing themselves of the patriarchal values, that Tomie has opened their eyes, and they have become hardened to the rules of society and how women are “supposed to” act.

She frequently sneers at the state of the world and makes cutting comments about the way humans uphold these twisted values. In Tomie, she reminds us of the “happy life” laid out for women historically, saying, “You will marry an incapable guy one day, and give birth to a dumb kid. You will be a wrinkled old lady soon. This is so wonderful. This is the happiness of being a woman. Since I am a monster. I will be as lovely forever.” It is hinted at that Tomie could be centuries old, so she has seen the worst of humanity, and her hatred has grown with time. Like in Begins when she discusses the characteristics of humanity she has seen

It seems to me normal humans are freaks. Bowing down to their superiors, exploiting the weak. Unaware of their stupidity, just deceiving, jealous, and calmly betraying others. Reiko, shouldn’t we call those people freaks? I believe in no one, depend on no one. I made that firm vow. I decided to live my life alone. I’m not lonely. Better to wander alone than have my trust betrayed.

And in Revenge, she unleashes her true feelings on the state of the patriarchy:

You, and all men everywhere, should just die!—They’re so stupid they’re disgusting! If all men were gone from the world, war would cease to exist. Also, the misery and terror. Far fewer children sacrificed to war. I don’t want to see such suffering in the news anymore! For that reason, there is no choice but to kill all men.

These moments, where she points out the observations she has made on human society and the cruelty that has and continues to destroy the world, are not completely off base. And her presence acts as a challenge to those with whom she comes in contact. She allows them to betray each other and hurt each other, and in this way, they never fail to disappoint her. And in some ways, it seems she even targets men who have proven themselves to be creeps and perverts. In Forbidden Fruit, she goes after the middle-aged father of a friend, who is always eyeing her friends, making her not want to bring them over. And in Beginnings, it is the school teacher whose “desirous lecherous eyes” she has seen watching her.

One of the most poignant scenes that was from the manga and has also appeared in Beginnings, as well as the animated series Junji Ito Collection, is when Tomie is murdered on a class trip. The teacher tries to control the situation by turning this into a group project. As they rip apart the body and each takes a piece they are responsible for throwing away, he talks them through an anatomy lesson. He even discusses how it would be unfair for their classmate, her boyfriend, to go to prison when he has his whole life ahead of him. An excuse used in far too many trials of men who have done terrible things to other people. And by everyone joyfully participating, they are all carrying the blame for her demise, and that of girls like her. The lives of girls and women are often undervalued in the service of protecting the status quo, and now that we live in times where men are excited for AI-generated sex bot girlfriends, it is all too clear that men care less about equality and fixing their toxic masculine traits, then they do about finding ways to get sex and validation without all the complex emotions. Like other monstrous feminine, her values align with those that are seen as bad or taboo within her culture. She is often compared to a devil, succubus, or a monster. Unlike the typical dead girl, she is not held up as a martyr or an ethereal figure because her overt bad behaviors ultimately go against what is valued and upheld. In the dead girl story, the dead body is often an object that is used as a plot point for other people to tell their stories. It is yet another way that women are objectified. Often, the reason the ‘dead girl’ ends up dead is because of a man who covets her youth and beauty and wants it for themselves. While girls like Laura Palmer finally got to tell their own story thanks to Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, too many real women never get the chance. And that number is even lower when we think of bipoc, trans, and queer folks. Women are often taught that their bodies can make men crazy. Instead of getting to the root of these problems, time is spent policing girls’ clothing and asking assault victims “what they were wearing”. With her constant return, Tomie makes them confront their sins. And makes us, as the audience, confront our obsessions with the dead girl and violence towards women. Tomie comes back as a reminder to her murderers that they cannot forget her. As she haunts these men, she also haunts those implicated in the violence: friends, families, and girlfriends. She is a “monster” because she reminds us of the monstrous inside of us.

Leave a comment