By Mo Moshaty

A woman alone, breath heavy, body trembling, birthing something unspeakable. Whether it’s Nola Carveth (the late and ever lovely Samantha Eggar) in The Brood or Margaret (Rebecca Hall) in Resurrection, the air thickens with that same sound pain turning linguistic, the body deciding to speak itself.

Horror, more than any genre, understands that silence has a shelf life. When therapy fails, when words curdle in the throat, horror provides the outlet: the scream as thesis. It is, in many ways, therapy’s shadow twin – a place where the unspoken finally finds form.

Cronenberg’s The Brood (1979) and Andrew Semans’ Resurrection (2022) are mirrors across time, refracting the same light through very different lenses. In the late 1970s, Cronenberg’s world was clinical and distrustful of emotion. Womanhood was pathology and motherhood the Petri dish. The Brood imagines womanhood as contagion, the womb and woman under surveillance. Emotion turned grotesque. A woman’s mental state now medical theater.

Decades later, Semans’ Resurrection meets us in the aftermath. The lab coats and alternative therapies are no longer force fed; they’ve been replaced by smart business dress and glass offices. Margaret is the experiment. In both films, birth, isolation and rebirth are not healing – they’re remembrance. It’s the horror of finally feeling again, even if that feeling is heinous.

Cronenberg’s Womb of Rage

If Cronenberg had written The Brood today, the opening credits might simply read: based on true emotional events. His “Psychoplasmics” therapy, a pseudo-scientific technique in which repressed emotions manifest physically, is the perfect horror metaphor for repression’s collateral damage. Dr. Raglin (Oliver Reed) plays God using therapy to extract catharsis from his subjects, like pus from a wound.

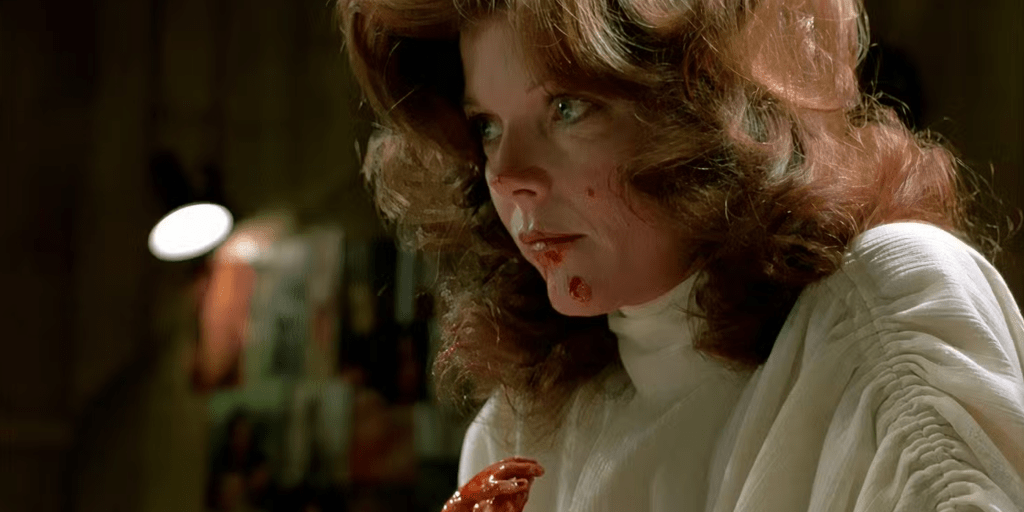

Nola Carveth becomes the genres most tragic patient. Her pain literally reproduces. Each broodling a fleshy footnote to male authority’s failure to listen. Every insult, every bruise, every bottled up scream finds embodiment in those small sexless creatures that emerge from her skin. The children are not offspring; they’re evidence. Somatic memory made visible.

Cronenberg frames everything in sterile fluorescent light. The domestic scenes are almost colder than the Raglin’s therpy sessions. Here, motherhood is less miracle than experiment, a case study in control. Dr. Raglan isn’t cutting into flesh; he’s cutting into the idea that women’s emotions are diseases to be managed and isolated. Nola’s final birthing scene is both grotesque and divine. She licks her newborn creature clean like an animal, reclaiming instinct. As though daring the audience to look away from what they forced her to become. It’s Barbara Creed’s monstrous-feminine in its rawest form: the womb weaponized. Cronenberg’s horror has always been interested in what happens when the body refuses metaphor. In The Brood, the metaphor claws its way out and starts killing people.

It’s 10:00 PM. Do you know where your glass paper weights are?

Resurrection and the Modern Monstrous-Feminine

Where The Brood externalizes rage, Resurrection internalizes manipulation until it becomes indistinguishable from faith. Margaret is not a patient; she’s both victim and witness to a psychological haunting that no one else can see.

Years earlier, her abuser David (Tim Roth) convinced her of an impossible horror; that he had eaten their infant son, and that the child still lives inside of him. It’s a grotesque act of gaslighting, a trauma ritual so extreme that it blurs myth and memory. David doesn’t just control Margaret through fear, he rewrites her biology. Every glance, every word, every false kindness feeds the fantasy that her pain is still breathing somewhere, and that she alone is responsible for keeping it alive.

Semans’ film inherits The Brood’s DNA but reclaims it through subjectivity. Where Cronenberg’s camera diagnosed Nola, Semans’ camera believes Margaret. Her body becomes a site of haunted devotion, her composure the mask of someone who has learned to parent her own terror.

Hall’s monologue is a séance of it’s own; trauma made verbal, belief made flesh. Delivered in one unbroken take, it becomes a kind of emotional autopsy. By the film’s end, Margaret’s mind folds in on itself: she performs a delusional surgery, ‘delivering’ her son from David’s belly in a moment that is both transcendence and tragedy.

She’s doesn’t give birth to monsters. She gives birth to the possibility of finally having control, however fractured, however imagined. Her act is reclamation, but also a surrender. The only way she can survive the lie is to make it real.

If The Brood is a film about men forcing women to manifest their pain, Resurrection is about a woman so gaslit by motherly love that she becomes her own mythmaker.

The Shared and Weeping Wound

Across forty years, both films orbit the same wound: women punished for expressing pain. In The Brood, the punishment is institutional, her emotions are weaponized by therapy. In Resurrection, it’s intimate, David is whispering from within her, he’s everywhere all at once.

Both stories use the language of the body to translate psychological truth. The difference is in authorship. Nola’s pain is appropriated by men who study it. Margaret’s pain is appropriated by a man who loves to control her. Either way, the result is the same: a woman forced to become evidence of her own suffering.

Horror has always feared what women might say if allowed to narrate their own trauma. These films imagine what happens when they stop asking permission.

The Brood presents hysteria as pathology; Resurrection reframes it as a survival strategy. One is clinical, the other compassionate. Cronenberg studies Nola from behind glass and a secluded forest cabin; Semans’ stays close enough to smell Margaret’s panic.

The images rhyme across time. The Brood’s slick, blood-soaked birthing scene: the body as manifesto. Resurrection’s closing delusion: the body as gospel. Two generations of horror, one continuous scream.

Neither film offers healing. Instead, they give us ownership of the wound. Both women take back authorship for their pain, even if it means becoming what the world fears: women who are too much, too loud, too trusting.

Horror gets that sometimes survival looks like madness, and sometimes madness is the only way to survive. When the body finally remembers, it doesn’t apologize. It roars, and in that roar lies horror’s truest act of resurrection; the insistence that even a broken truth is still a truth.

Leave a comment