By Victoria Hood

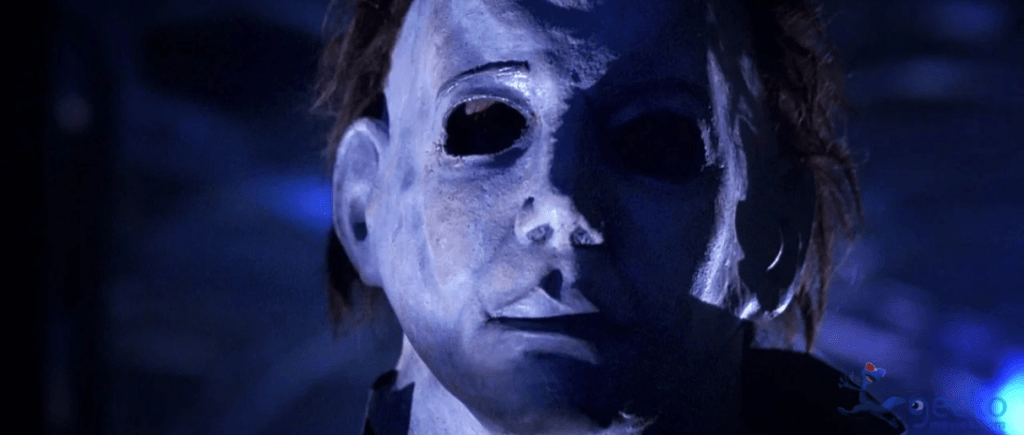

Every time I peer out my window, I know in my heart it could be the day I finally catch Michael Myers waiting for me outside again. He visited me, back when my siblings and I were all single digits. Our aunt watched us, waiting until our parents got home. She wasn’t his normal teenage victim, but every sequel needs a new angle. Our father finally gets home, and we are sad to see that our aunt is already packed up and ready to leave. My siblings and I line up at the window to watch her make it safely outside, and our hearts start pounding: Michael Myers is here. We know that it is never good news.

I like to picture myself hand-selected for my family, but I think this is a naive reach towards control in a world where we get so little. To hand-select myself would also mean someone hand-selected my siblings (wonderful news) and our parents (standard news), and our other relatives (bad news) to put us all together to watch each other die. I grew up in a family obsessed with death; a family that liked to watch horror and make others watch horror. In this family, we pass down legends about hairy hands that grab siblings, ghosts that haunt our houses, we dare each other to try Bloody Mary and Candyman, and we tell each other urban legends are real. This makes it easier to understand why our family goes missing, why we are gathered at a funeral home again and again. We’ve seen this in the movies—grief, mourning, blood outside of bodies, and tears leaking from eyes. Like Michael Myers haunting the town of Haddonfield, my family has been haunted by addiction and mental health struggles, both leading to a slashing of the family line until there are barely enough people left to make a tree.

I imagine the opening scene of Halloween (1978): Michael approaches his sister with his view covered by his mask in the same way I imagine mental health with no resources shrouds our view of drug use. I believe Michael thought that murder could bring him some happiness, some relief, some specific feeling that could solve things. I believe so much of my family thinks that opioids and heroin, and pills, could bring them some happiness, some relief, just a moment of peace from their minds and poverty. My mother figuratively tries his mask on for size. Even my young brain knows this is not her first mask; her depression was a mask she was born with; her loss of control as she grew her family, as her body changed and broke, led her down a path of trying more and more masks—Which of her masks—depression, denial, or the distressed William Shatner face—could possibly hide her tears?

We’re all running now! There are three of us kids, roughly five through nine, and we are running like children who think they are about to die. My brother grabs a mallet, and my dad takes it from his hands because weapons are for adults. My sister falls on the floor as we all try to run and hide in our shared bedroom. My brother and I just keep running, keep hiding, we leave her behind in hopes that she can protect herself. Michael Myers approaches her. I don’t see any of this because I am stuffed so far into the corner with my eyes shut. I feel the weight of Michael sitting on the bed, I hear the sobbing of my sister, and my grief clock begins to tick.

I enjoy the timeline of Halloween where Michael and Laurie are siblings, even if it doesn’t make as much sense as the versions where they aren’t. It feels almost peaceful, the chasing of a sibling until you finally get them. My childhood was full of chasing siblings, chasing parents, chasing our cousins, aunts, and uncles. Even with a knife in hand, there is something inherently understood about tracking a sibling down and trying to scare them. The search for some peace that may only come through the ending of his family line. I don’t think he is right. Even if Laurie Strode did not have children, their family would still live on in newspapers and magazines, in the stories people tell about that infamous Halloween. What I enjoy about this timeline is the way in which we see Michael search for connection, even if it is out of the desire to end it. There is a codependency in the ways they cannot live beyond one another; even if there was an end for one of them, the other would have their life defined by the other. Isn’t that what family is? People are defined by the people who made them who they are.

I want to be defined by my family. I can’t think of describing who I am without acknowledging the grief in my bones. I am made up of their deaths like I am made up of the memories of us all alive. There must be memories plaguing Michael, though this depends on how you view his humanity. In the Rob Zombie remakes, Michael is meant to be completely evil, yet we see an upbringing that teaches him the opposite of nurture and kindness. If we never see our families care for themselves, then where are we supposed to learn it? Like Michael in the remakes, my family grew up with a lack of resources. Like many poor families, there were no outlets for mental health struggles, and it is hard to know how to cope differently when we have no guidance on how to do so. When violence is baked into our bones, seared into our memories with no guidance on how to carve it out, it only becomes harder and harder to know when to put down the knife.

I hear my mother’s voice in her soft and gentle tone, informing my sister that it was just her all along. The monster was never real. It was just our mother. There is no murderer. It was just our mother. Our father and aunt aren’t actually worried—look at them, they’re laughing. It was just our mother.

My mother is dead now. I no longer feel her hand rub my back as she consoles me. Michael is as alive as ever. I can feel him lingering just over my body, the same way I feel my family line watching to see which drug I will pick up. My siblings and I tell this story like it is a memory that does not scare us; rather, this is a memory that made us. We watch at least one Halloween movie a year, and each time we do, it feels like a way of preserving our past. We faced Michael Myers and survived. Who else can say that? In our family, we faced generations of Michael Myers, and none of us has been slashed down yet.

Our aunt, who babysat us, is also dead now. The family line of addiction did not skip the babysitter, even if she did outlast Michael. Up until her death, I would gift her different Halloween memorabilia and paraphernalia because I knew she would love it. I have her last gift hanging in my house—a knife with the Halloween logo on one side and “Haddonfield, IL” on the other. I’ve given her snowglobes and masks, and every time I see a glimpse of Michael, I think about how she protected us. She knew we were never in danger from Michael, but I believe her defenses were rooted further down inside of her. She knows what it is like to lose siblings and parents; she knew she wanted differently for us. In her misguided heroic efforts, she wanted to protect us from every family curse that might be following us.

What saves Laurie time and time again is an understanding of the genre she is in. When the movie begins happily, we see that she does not simply smile and move on. We see that she can always feel him hovering right above her. She is quick to understand that even if she is happy and at peace now, things can change in a moment. When I look outside at night, I brace myself for the image of Michael staring back at me. I know, in a pinch, I can run and hide and shove myself in a corner, but I know this will leave my other family vulnerable. If Michael won’t stop lurking, if addiction and mental health issues are handed down again and again, I cannot lock myself away and hide. Instead, I must help my sister up and take her with me. I must give my brother his weapon back so he is prepared this time. We must stick together and prepare, you never know where Michael is hiding. This is our real test.

Image Credits:

Film still from Halloween (1978), © Compass International Pictures. Used for editorial purposes.

Film still from Halloween Kills (2021), © Universal Pictures / Blumhouse Productions / Miramax. Used for editorial purposes.

Leave a comment