By Ray Walton

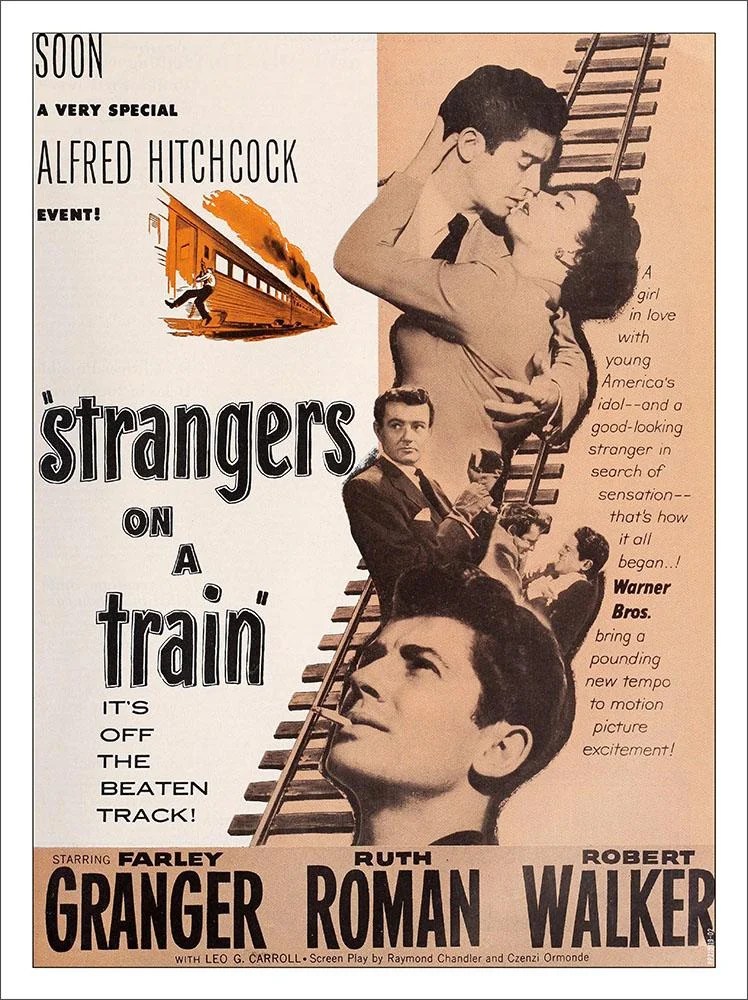

Strangers on a Train (1951) Director: Alfred Hitchcock ⭐️⭐️⭐.5

A psychopath tries to forcibly persuade a tennis star to agree to his theory that two strangers can get away with murder by submitting to his plan to kill the other’s most-hated person.

Released in 1951, Strangers on a Train sits at the intersection of classic noir and Hitchcock’s fascination with guilt, doubles, and moral entrapment. Adapted from Patricia Highsmith’s novel, the film explores the dangerous intimacy of chance encounters and the idea that violence can be outsourced, rationalized, or displaced.

Arriving during a period shaped by postwar anxiety and rigid social codes, the film reflects fears about identity, repression, and the thin line between civility and monstrosity. Hitchcock’s visual precision elevates the story beyond its premise, crafting moments that remain etched into cinema history. The film’s tension is less about whether violence will occur and more about how closely it will cling to those who try to deny responsibility.

This is not one of my favorite Hitchcock films, but it is one I return to every now and then because there is still so much to admire. The first time I watched it at nineteen, I was aware that Bruno was coded as gay, but if it had not been pointed out to me, I might not have noticed. Revisiting the film years later, his mannerisms and behavior make that coding unmistakable.

It is frustrating to recognize how often queer-coded characters were positioned as villains during this era. At the same time, there is an uncomfortable tension there because villains are often the most compelling figures on screen. Robert Walker unquestionably steals the film, giving Bruno an unsettling charm that lingers long after the credits roll.

Visually, the film remains striking even more than seventy years later. Miriam’s death, reflected in her fallen glasses, and the chaotic climax on the merry-go-round are reminders of Hitchcock’s ability to stage suspense with unforgettable imagery. Watching those scenes now makes me aware of how much my own appreciation for film has grown over time.

I still feel conflicted about Bruno’s queerness. The portrayal is dated, and its implications are uneasy. Yet there are moments when there is nothing quite like a gay villain, for better and for worse.

Why tonight?

Because this is a film about shared guilt, and winter nights make it harder to pretend we are uninvolved.

Leave a comment