By Mo Moshaty

Horror has a habit of congratulating itself too early.

A character escapes. They’re breathing. They’re standing. Sometimes they even walk into daylight. The implication is clear. This is success. The worst is over. The story has done its job.

But horror’s visual language often tells a different story, one it seems reluctant to acknowledge out loud. Survival, in these films, is physical. The body makes it through. The psyche is left suspended, altered, and largely unaccounted for. What remains looks less like triumph and more like damage that has learned to move.

This is where horror quietly contradicts itself. It frames survival as victory while staging endings that feel anything but victorious.

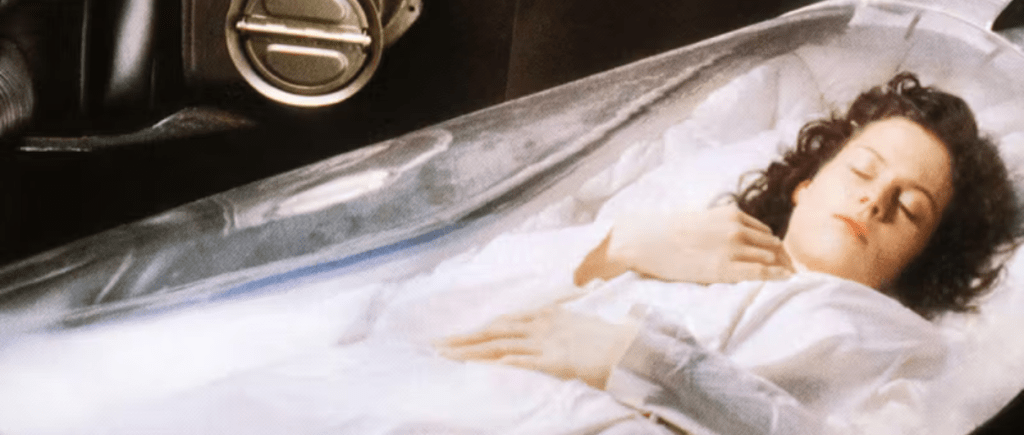

In Alien, Ellen Ripley survives through competence, vigilance, and a relentless refusal to die. The film appears to reward this. She outsmarts the creature. She escapes the ship. She is alive when the credits roll.

And yet, nothing about the final act resembles safety.

Ripley ends the film alone, stripped of community, suspended in space, speaking to no one. Her survival is conditional and temporary. The cryosleep chamber is not peaceful; it’s a postponement. The film’s closing imagery doesn’t suggest that Ripley has won per se, only that she has not yet lost again. We do find out in Aliens that Jonesy is okay, so all fine there.

What Alien understands, even if it doesn’t fully articulate it, is that survival does not restore equilibrium. Ripley’s competence keeps her alive (sorry, men), but it cannot undo the isolation the film has already imposed. The victory is logistical, not emotional. She lives, but the conditions of living have narrowed dramatically.

Green Room pushes this logic further by refusing any illusion of heroism. This band is 100% in the shit. Survival here is not earned through skill so much as attrition. Characters survive by chance and by the grim luck of being less injured than the person next to them.

When the film ends, those who remain standing are visibly diminished. Their bodies are intact enough to function, but their faces, posture, and silence tell a different story. There’s no sense that what they’ve survived has granted clarity or strength. The film doesn’t offer them meaning, only continuation…barely.

Green Room refuses the fantasy that survival produces growth. It frames survival as depletion. Something has been used up. Something is gone. The film doesn’t ask us to celebrate the survivors; it just acknowledges that they are what’s left.

Then there is The Descent, a film that understands how cruel the idea of victory can be.

Depending on which ending one encounters, the film offers either escape or illusion. In both cases, peace is absent. Even when the protagonist appears to survive, the visual language insists otherwise. Her body may emerge from the cave, but her interior world doesn’t follow. The trauma remains subterranean, unresolved, and consuming.

The Descent stages survival as a rupture rather than a resolution. The cave isn’t left behind, it’s crawled inside. The film’s final moments refuse restoration, insisting instead that some experiences collapse the distinction between escape and entrapment.

What links these films isn’t tone or setting so much as a quiet mismatch between what the story says and what the image shows. Survival is offered as an ending, but the frame rarely agrees. The body gets out. The mind stays put.

Horror has always liked the idea of survival as proof. You made it. You stayed alert. You followed the logic of the world you were dropped into. Living, in this framework, reads as a kind of moral clearance. But that equation only really works if being alive also means being okay, and these films seem deeply unconvinced by that math.

What they give us instead are survivors who function. They walk. They speak. They comply with the basic requirements of being alive. What they don’t do is settle. The camera notices this even when the narrative would prefer not to. It hangs back. It waits. It watches characters sit in silence a beat too long. Safety exists, but it feels temporary, conditional, or vaguely theoretical.

This doesn’t feel like a mistake so much as a hesitation.

Horror wants survival to feel like success because success is tidy. It gives the audience a place to stand before leaving the theater. It suggests the damage has been contained. But the images these films linger on don’t quite support that reassurance. They suggest that surviving is less a reward than a new set of conditions, ones the story doesn’t have time or interest to fully explore.

What’s interesting is how often the genre seems aware of this even as it moves past it. The visuals keep whispering after the plot has wrapped up. Faces don’t relax. Bodies stay braced. Rooms feel wrong even when they’re quiet. The threat may be gone, but the posture of threat sticks around like muscle memory.

Horror loves a winner. It just doesn’t spend much time asking what they’ve actually won.

In these films, survival reads less like triumph and more like continuation. Life goes on, but it goes on sideways. The characters move forward carrying something unnamed, something the story leaves behind with the rest of the wreckage.

Leave a comment