By Mo Moshaty

Let’s be honest. Horror knows we’re waiting for a certain cue. A synth stab, a shadow, “girl, you better run, dammit!” moment.

But horror endings have a different flavor. The monster is defeated, revealed, or sent to the hell from whence it came. We’re invited to relax and accept that whatever came before has been contained. Survival should feel like relief…amirite?

Some films don’t give us that satisfaction. In these stories, the monster doesn’t need to win. It doesn’t even need to stay. Leaving is enough. The real work has already been done elsewhere, inside spaces, bodies, and relationships that don’t snap back into place once the danger recedes. What’s left behind isn’t suspense, but consequences.

This is where After Horror begins to take shape on screen, not as escalation, not as aftermath, but as the uneasy recognition that survival has changed the terms of living in ways no ending can fully resolve.

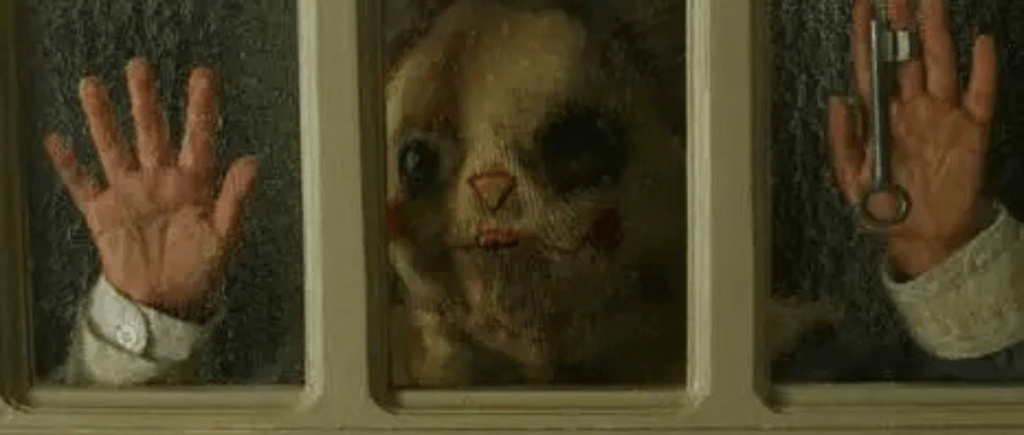

In Relic, the question of the monster is almost beside the point. Decay moves through the film and the family without urgency. The house doesn’t feel invaded so much as inherited. The walls narrow, the rooms repeat themselves, and there’s Post-its everywhere. It’s like M. C. Escher threw up in there. The bodies slow, they forget, and they soften at the edges. And whatever horror exists here doesn’t announce itself as something to be defeated, but something to be navigated. Even when the confrontation does arrive, it doesn’t offer any restoration or consolation.

The film gets that survival doesn’t reverse decline, it reframes it. And what it lingers here isn’t fear, but responsibility. Care persists because it has to, but it does so under conditions that grow heavier rather than lighter. Nobody’s leaving this film unburdened. That decay is getting passed down in real time. From Edna’s full-focused decay, to Kay being next in line to hold the Alzheimer’s baton, to Sam, who knows she’s going to have to watch her mother fall apart just like her mother is. And that’s so incredibly emotionally damaging to know that your parent is basically going to die twice. And here, the monster, such as it is, never really leaves because it was never the point.

Relic is interested in what it means to stay close to something that frightens you, because leaving would mean abandoning what you love. The After Horror, here, is about remaining present when disappearance isn’t an option.

His House approaches the same territory, but from a different angle. Its monsters are loud at first, insistent and physical, but even as they recede, the film refuses to soften. Survival doesn’t bring freedom, but further displacement. The house has survived, and they’ve survived the journey, but the haunting has endured, and still, nothing feels settled. Nothing feels fixed. Nothing feels rectified.

What the film marks is that leaving one horror for another doesn’t guarantee that you’ve escaped its logic. The couple’s survival is marked by vigilance, guilt, and the persistent feeling of being watched and assimilated, even when no one is there. The spirits’ departure doesn’t restore their safety, but it confirms that safety was never really part of the deal.

The visuals do most of the work here. Tight frames, crowded interiors, and bodies that never fully relax. We’re watching Bol and Rial in a bell jar. The threat may be gone, but the posture of threat remains. After Horror is not a new chapter. It’s the same story told under quieter albeit terrifying conditions.

Then there’s The Orphanage, a film that appears to offer some closure, but does so with a gentleness that feels pretty sus. The haunting is explained, the mystery is resolved, and the ending gestures towards some sort of peace. And yet something about it refuses to sit with us comfortably. The film gives the audience what it wants more than it gives the characters what they need. Understanding replaces escape, meaning replaces repair. The monster is gone, but the loss remains absolute. What looks like an ending is closer to acceptance, shaped by exhaustion. Our girl has been through it.

This is where the film’s After Horror asserts itself. The ending doesn’t undo grief but compartmentalizes it into something bearable enough to live with, which is the most we can all hope for. The screen goes dark, not because anything has healed, but because the film has chosen to stop looking and stop caring.

Across these films, the monster’s departure doesn’t signal success, but a shift. The threat no longer needs to dominate the frame because its effects have already been absorbed, and what we’re left with is survival stripped of any triumph and life continuing under altered conditions.

Horror often tells us that defeating the monster is the whole point. These films suggest something completely different: that the monster never was the point, and that the real disturbance lies in what remains once the noise fades and the work of the living resumes.

After Horror on screen is about what we’re asked to live alongside once escape is no longer possible. The monster leaves, sure, but the story doesn’t resolve itself around that departure. It just becomes quieter, heavier, and more honest.

Some horror ends when the monster is gone. The most unsettling kind begins there.

Leave a comment