By Tuğçe Kutlu

Contemporary horror cinema has increasingly repositioned death not as an endpoint but as a site of ongoing negotiation between presence and absence. Within this shift, Talk to Me (Philippou & Philippou, 2022) emerges as a particularly incisive exploration of the human compulsion to sustain contact with the beyond. Rather than staging the afterlife as a distant metaphysical domain, the film situates it at the level of sensation, embodiment, and social ritual. Its central horror derives less from supernatural intrusion than from the emotional insistence that the dead must remain reachable.

At the level of genre history, possession narratives have typically been structured around invasion. Classic examples such as The Exorcist frame possession as a violation of bodily and spiritual boundaries, often resolved through religious authority. In Talk to Me, however, possession is elective. The characters line up to experience it. This inversion shifts the moral architecture of the subgenre. The threat does not originate in transgression but in participation. The séance is not a forbidden act discovered too late. It is a social practice that gains legitimacy through repetition.

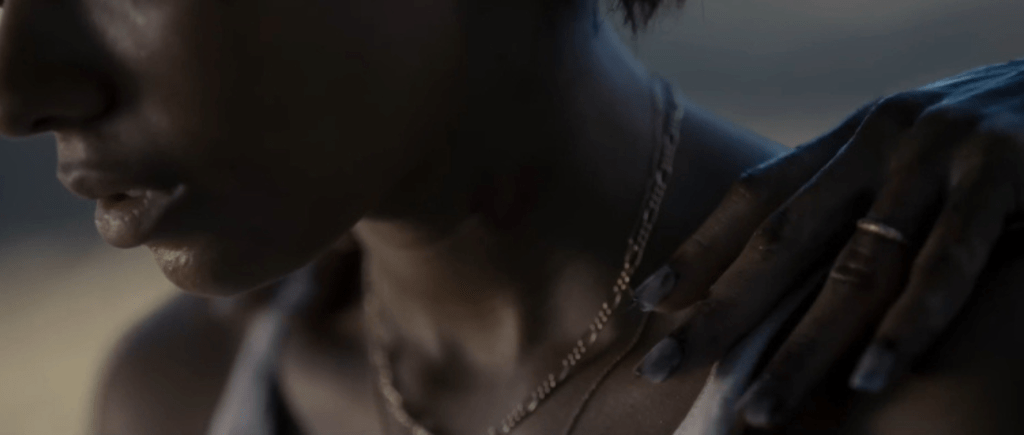

This reframing aligns with broader theoretical observations about modern horror’s turn toward internalised rather than externalised threats. Noël Carroll argues that horror frequently functions through the disruption of categorical boundaries, particularly those separating life and death 1(Carroll 1990). Talk to Me literalises this disruption by transforming the boundary into something tactile. The embalmed hand operates less as a cursed relic than as an interface, an object that converts desire into encounter. The phrase “talk to me” functions as an invocation of proximity rather than knowledge. What is sought is not metaphysical truth but confirmation that absence can be reversed.

The film’s emphasis on ritual is crucial to this dynamic. The ritual surrounding the hand, grasping it, speaking the phrase, and counting the seconds creates a measurable structure around an otherwise chaotic supernatural event. Ritual has historically provided mourning cultures with symbolic containment, allowing grief to be processed within shared frameworks of meaning 2(Kerrigan 2007). In Talk to Me, in contrast, ritual appears stripped of cosmology. It is communal but not sacred, repeated but not inherited. Without an interpretive structure to stabilise the experience, the séance functions less as a mechanism for processing loss than as a technology for intensifying it.

This distortion of ritual reflects a broader cultural condition in which traditional mourning practices have been weakened or privatised. Sociological accounts of modern death culture note that Western societies increasingly distance everyday life from visible encounters with mortality, producing what has been described as “complicated” or prolonged grief responses3 (Worden 2018). The séance in Talk to Me emerges within precisely such a vacuum. It offers an improvised means of contact that bypasses slower, socially mediated processes of mourning. Instead of remembrance, the film offers immediacy.

The desire driving this immediacy is not curiosity but yearning. The protagonist’s engagement with the ritual is rooted in unresolved grief for her mother, situating the supernatural encounter within a familiar psychological framework. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and David Kessler describe mourning as involving a gradual recognition that the deceased “will not return,” even if this recognition is uneven and non-linear4 (Kübler-Ross & Kessler, 2005). Talk to Me is structured around resistance to precisely this recognition. The séance promises what mourning withholds: presence without finality.

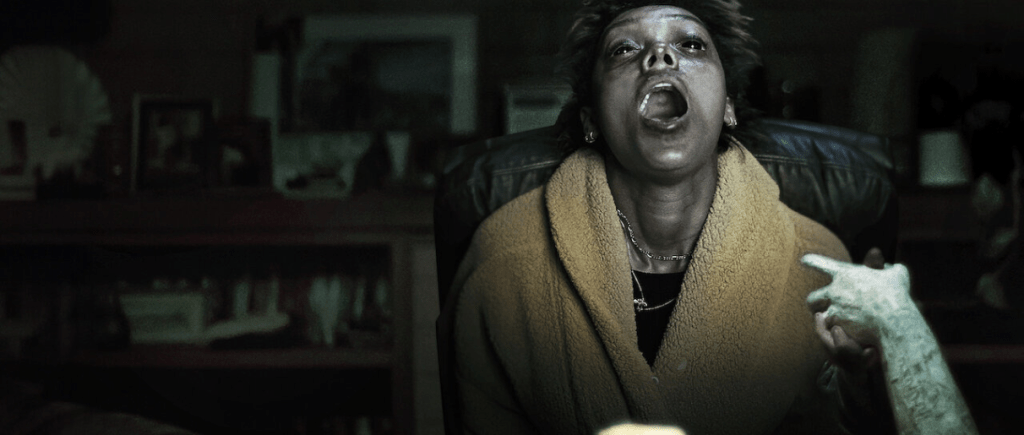

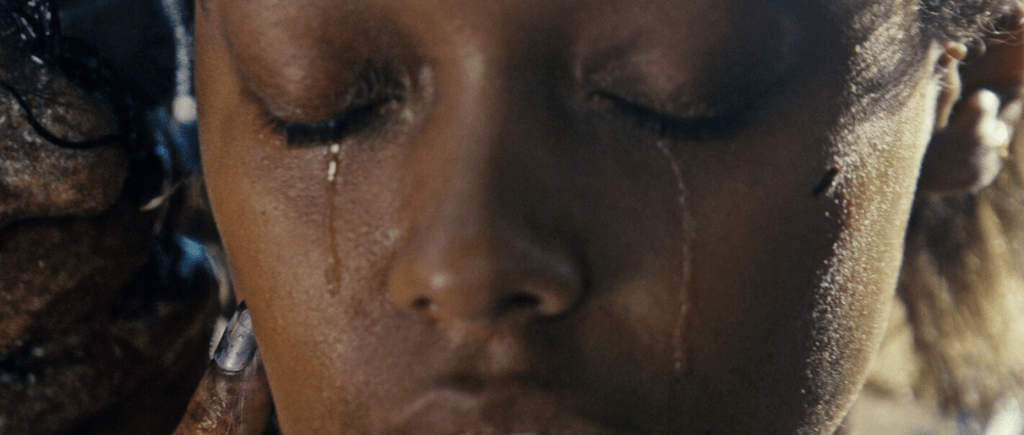

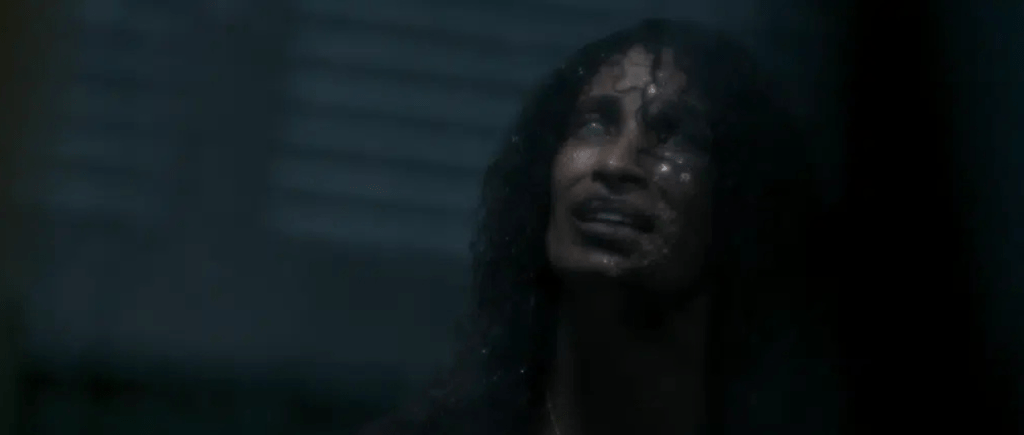

Talk to Me (2022) dir. Philippou & Philippou/Causeway Films

This promise, on the other hand, is destabilised by the film’s persistent ambiguity about the spirits’ identity. The entities that appear may resemble loved ones, yet resemblance does not guarantee authenticity. Richard Armstrong’s work on mourning cinema suggests that ghostly apparitions often function as projections shaped by the mourner’s expectations rather than as stable ontological presences5 (Armstrong 2012). Talk to Me amplifies this uncertainty by presenting encounters that are at once intensely intimate and epistemologically unreliable. The afterlife becomes indistinguishable from the emotional need that summons it.

The film’s insistence on bodily possession further intensifies this ambiguity by relocating the boundary between life and death from space to flesh. Earlier ghost narratives frequently externalise haunting through architecture, as seen in The Woman in Black, where the haunted house operates as a spatial metaphor for unresolved mourning. In Talk to Me, the body itself becomes the haunted site. This shift resonates with trauma theory’s observation that overwhelming loss is often experienced as a form of psychic occupation, in which the subject feels “possessed” by intrusive images or memories6 (Caruth 1995). Possession here is not merely a supernatural spectacle but a literalisation of grief’s capacity to dominate perception and agency.

The experiential quality of the possession sequences also aligns the film with recent horror texts that treat grief as an embodied condition rather than a narrative backstory. Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook famously renders mourning as a monster that cannot be destroyed but must instead be contained. Similarly, Talk to Me suggests that contact with the dead does not resolve grief but amplifies it, transforming longing into dependency. The ecstatic reactions of the participants, moments of euphoria, dissociation, and loss of control, recall the paradoxical attraction to death that horror frequently stages as both terrifying and seductive (Worland 2007).

The social dimension of the ritual is equally significant. The possession sessions are recorded, shared, and replayed, turning encounters with death into a collective performance. This dynamic reflects the increasing mediation of grief within contemporary culture, where mourning is often performed within visible networks rather than confined to private spaces. Scholars have noted that late modern societies are characterised by highly public displays of mourning following large-scale tragedies, suggesting that grief has become both communal and mediated7 (Kerrigan 2007). In Talk to Me, the séance becomes a peer-driven performance in which emotional intensity is validated through visibility.

Yet this visibility does not produce solidarity. Instead, it generates escalation. Each session must be more extreme than the last, each encounter more intense. The ritual thus mirrors what Robin Wood identifies as horror’s capacity to externalise repressed social anxieties in forms that escalate rather than resolve ideological conflict8 (Wood 1986). The boundary between experimentation and compulsion erodes, and repetition becomes its own justification. The more frequently the line between worlds is crossed, the less stable it becomes.

At the core of this escalation lies a temporal refusal. Mourning requires an acknowledgment that the past cannot be re-entered, that the relationship with the dead must shift from presence to memory. The séances in Talk to Me offer a seductive alternative by suspending ordinary time. For brief intervals, the living appear to share a moment with the dead. This suspension echoes Freud’s observation that mourning involves a difficult detachment from lost objects, whereas melancholia remains fixated upon them9 (Freud 1917/2005). The ritual enables a melancholic loop in which detachment is perpetually deferred.

The entities that respond to the invitation complicate this loop by appearing opportunistic rather than benevolent. Their persistence suggests that the afterlife, when approached as a service rather than a mystery, becomes predatory. This dynamic recalls Stephen King’s narrative logic in Pet Sematary, where attempts to reverse death result not in restoration but in corruption. In both texts, the desire to restore what was lost becomes the mechanism through which loss is intensified.

The film’s bleakest implication is that proximity to the dead destabilises the living. If death is no longer distant, it cannot be symbolically contained. Carroll’s account of horror emphasises that monsters frequently occupy liminal states between categories, provoking fear precisely because they resist classification10 (Carroll 1990). The spirits in Talk to Me occupy such a liminal position, existing somewhere between memory, hallucination, and independent agency. Their presence erodes the distinction between internal grief and external threat.

Ultimately, Talk to Me presents grief as a threshold condition that suspends the mourner between worlds. The ritual promises connection but produces entrapment. Instead of facilitating closure, it creates a feedback loop in which longing generates further longing. The characters do not cross into the afterlife. They hold the boundary open, insisting that one more attempt might provide certainty.

The film’s central insight is that the desire for contact is both human and structurally dangerous when it replaces acceptance. Mourning traditionally requires learning to live with absence, to reconfigure relationships through memory rather than presence. Talk to Me imagines the nightmare alternative. A world in which the dead remain reachable and the living, therefore, remain unable to re-enter ordinary time.

In this configuration, horror does not emerge from the existence of spirits alone but from the impossibility of separation. The most disturbing possibility is not that there is nothing after death, but that something remains — and it answers back.

- Carroll, N. (1990). The Philosophy of Horror, or Paradoxes of the Heart. New York: Routledge. ↩︎

- Kerrigan, M. (2007). The History of Death: Burial Customs and Funeral Rites from the Ancient World to Modern Times. London: Amber Books. ↩︎

- Worden, J. W. (2018). Grief Counseling and Grief Therapy: A Handbook for the Mental Health Practitioner. 5th edn. New York: Springer. ↩︎

- Kübler-Ross, E. and Kessler, D. (2005). On Grief and Grieving: Finding the Meaning of Grief Through the Five Stages of Loss. New York: Scribner. ↩︎

- Armstrong, R. (2012). Mourning Films: A Critical Study of Loss and Grieving in Cinema. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ↩︎

- Caruth, C. (1995) ‘Trauma and Experience: Introduction’, in Caruth, C. (ed.) Trauma: Explorations in Memory. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 3–12.

↩︎ - Kerrigan, M. (2007). The History of Death: Burial Customs and Funeral Rites from the Ancient World to Modern Times. London: Amber Books. ↩︎

- Wood, R. (1986) Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan. New York: Columbia University Press. ↩︎

- Freud, S. (1917/2005) Mourning and Melancholia. London: Penguin.

↩︎ - Carroll, N. (1990). The Philosophy of Horror, or Paradoxes of the Heart. New York: Routledge. ↩︎

Leave a comment