by Paul A J Lewis

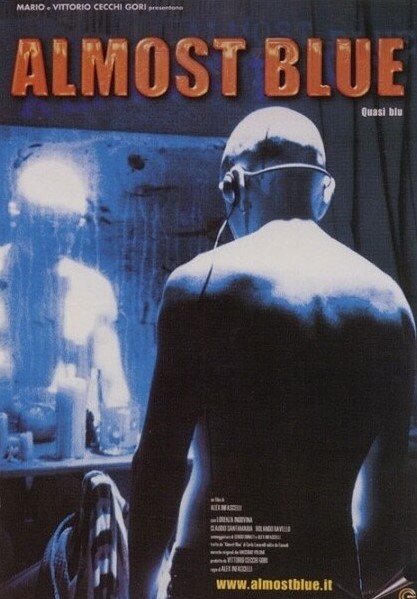

Almost Blue (2000)

A serial killer, called the Iguana, is terrorizing Bologna. He is able to change continuously identity. Grazia is investigating trying to find out the truth about the Iguana. Only a blind boy obsessioned by “Almost Blue”, a jazz song, could help her.

Adapted from the second of six novels by acclaimed Italian crime writer Carlo Lucarelli about young female detective Grazia Negro, a member of an elite unit tasked with hunting serial murderers, Almost Blue (2000) was the feature film debut of its director, and co-writer, Alex (Alessandro) Infascelli. (Coincidentally, the first novel in this series, 1994’sLupo mannaro, was adapted as a television movie during the same year as the production and release of Almost Blue.) The novel was adapted into screenplay by Sergio Donati, with Donati’s script apparently substantially revised by Alex Infascelli and his brother Luca.

In Almost Blue, Grazia (played in the film by Lorenza Indovina) is assigned to the case of a possible serial killer in Bologna by her mentor at the UASC (Unit for the Analysis of Serial Crime), Vittorio (Andrea Di Stefano). Managing the case in Vittorio’s absence, Grazia is given help in the form of members of the local polizia, Sarrina (Marco Giallini) and Matera (Dario D’Ambrosi). Initially, the polizia are resistant to the suggestion that the murders of several students, found naked and mutilated, are connected. However, Grazia manages to persuade them otherwise, after having used the UASC’s computer software to identify a pattern to the killings.

Grazia is contacted by Simone (Claudio Santamaria), a blind, housebound young man who lives with his mother (Benedetta Buccellato). Simone’s only contact with the outer world is the high tech equipment he uses to eavesdrop on private electronic communications, including telephone calls and Internet chat lines. Simone also demonstrates a curious synesthesia, imagining voices as colours. (For Simone, Grazia has a calming “almost blue” voice; hence the title of both the novel and film, which references the bluesy, haunting Elvis Costello song, used on the film’s soundtrack at several points in the story.) Overhearing a telephone conversation between Grazia and Vittorio, and also tapping into an online chat between the killer and one of his potential victims, Simone identifies the murderer as possessing an intimidating “green” voice. Grazia brings Simone into the investigation, and the two young adults eventually develop a romantic relationship.

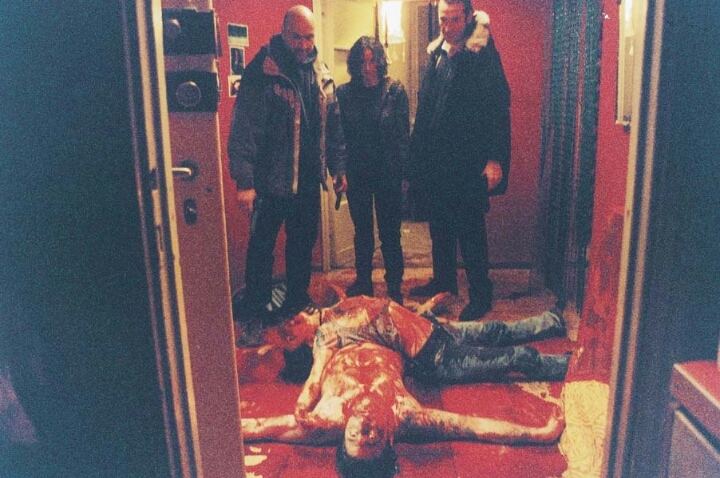

Through Grazia’s investigation, the killer is revealed to be Alessio “the Iguana” Crotti (Rolando Ravello), a troubled young man who was incarcerated in a mental hospital as a child after brutally murdering a peer. Freed from the mental hospital in a breakout staged

by his brother Raoul, who subsequently committed suicide, Alessio is obsessed with the idea of taking on the identities of other people. He kills his victims before assuming their identity, stealing their clothing and sometimes modifying his body to appear more like them. Thus the polizia are presented with a series of murders in which witnesses appear to see, near the scene of the crime, the victim of the previous murder in Alessio’s chain. However, as Grazia’s investigation leads her to Alessio, Alessio becomes aware that the net is tightening, and he develops a particular—and potentially deadly—fascination with Simone.

Much of Lucarelli’s work highlights the points of intersection between Italian noir (and neo- noir) and the giallo all’italiana (Italian-style thriller). 1

Italian noir and the giallo dovetail in interesting ways, both having their roots in Mondadori’s yellow-covered imprints, during the early/mid 20 th Century, of crime novels by writers associated with whodunits in the “English” style (such as Agatha Christie) alongside the work of hardboiled authors associated with American film noir (including James M Cain). Both the cinematic giallo and Italian film noir may be claimed to have their roots in Luchino Visconti’s Ossessione (1941), an adaptation of James M Cain’s novel The Postman Always Rings Twice—one of the books published by Mondadori.

Carlo Lucarelli’s novels marry elements of hardboiled crime fiction, focused on the processes involved in detecting and solving crime, with the lurid psychosexual thriller plots that are popularly associated with the gialli all’italiana of filmmakers like Dario Argento,

Riccardo Freda, and Sergio Martino. Almost Blue, in both its source novel and Infascelli’s film adaptation, is no exception to this. Lucarelli’s novel is told from three points-of-view, chapters written in third person and focalised through Grazia interwoven with chapters written in the first person and presenting the perspectives of, alternately, Simone and Alessio. Infascelli’s film adaptation translates this into its visual equivalent, with copious use throughout the film of prowling point-of-view shots from the killer’s perspective. It seems simultaneously necessary and redundant to highlight the extent to which Almost Blue’s

photographic foregrounding of the killer’s point-of-view connects Infascelli’s picture to the gialli of the 1960s and 1970s.

But also, on a narrative level, like the classic gialli that preceded it Almost Blue emphasises the curious psychopathology that underpins the murders committed by Alessio/the Iguana; these are murders seemingly driven by a desire for self-annihilation and Alessio’s need to crawl into the skin of his victims. (Lucarelli’s source novel contains a number of haunting

passages in which Alessio, narrating, describes the skin of his face splitting apart, enabling the lizard that he claims lives inside him to crawl out to devour his victims.) At one point in the film, Vittorio and Grazia converse about the murders; Vittorio suggests Alessio is “searching for his own identity,” and Grazia argues that the crimes are, for the killer, “a kind of reincarnation.” “He is the serpent in his own nightmares,” Vittorio concludes.

Neo-noir has been suggested to be distinct from classic noir specifically in the former’s self-conscious appropriation (and foregrounding) of narrative and aesthetic tropes that were organically developed within the latter, and a similar paradigm may be said to underpin the relationship between the classic giallo and the neo-giallo. There is no specific “cut-off” in terms of the progression from the giallo to the neo-giallo, though the label neo-giallo is often associated with Italian thrillers made around the turn of the millennium and after.

One of the earliest uses—if not the first use—of the term neo-giallo was in a 2002 article by British critic Alan Jones, in reference to Dario Argento’s 1997 picture The Stendhal Syndrome. Speaking of Argento, there are some notable similarities between Infascelli’s Almost Blue and another neo-giallo by Dario Argento, Il cartaio (The Card Player, 2004). Both feature female detectives battling against chauvinistic colleagues during their pursuit of a serial killer, and in both films video chat rooms play a major role in the investigation. This emphasis on media forms and representations is not particularly new within Italian pop cinema (one may think of Lamberto Bava’s 1985 film Dèmoni/Demons or Giuliano Montaldo’s 1978 thriller Circuito chiuso/Closed Circuit, in which a murder is committed amongst a cinema audience during the screening of a Spaghetti Western), but a fascination with the Internet and digital communications is a noticeable facet within a number of post-millennium neo-gialli. The exploration of this theme in Almost Blue and The Card Player feels very much like an attempt to narrativize anxieties about the growth and spread of electronic communications around the turn of the millennium, particularly in the fallout from the panic surrounding the “millennium bug” that failed to materialize.

In Lucarelli’s novel, Simone listens in to Internet chat lines via a device that translates the text typed into the chat software at the users’ end to computerised speech at Simone’s end of the connection. Whilst doing this, Simone accidentally eavesdrops into a conversation between Alessio and one of his victims; this is the event that precipitates Simone’s telephone call to Grazia, using a phone number Simone acquired when he illegally intercepted a previous call between Grazia and Vittorio. However, in Infascelli’s film adaptation we instead see Simone eavesdropping on a video chat room where Alessio converses with his prey.

In an early draft of the script for the film, credited solely to Sergio Donati, the scene is captured in a way that is more faithful to Lucarelli’s novel: Simone is described in the scene description as listening to “una strana voce meccanica, asessuata, priva di emozione, la stessa voce per tutti e due gli interlocutori.” 2 It’s fair to assume that during rewrites, the idea was posited that the scene, as described in the original script, wasn’t cinematic enough; and Simone’s use of text-to-speech software to eavesdrop on text-based chat lines was rewritten to incorporate video chat rooms. (On the other hand, it could be argued that there’s something even more uncanny about Simone’s ability to identify the “voice” of the Iguana solely through the content of his speech.)

Early in his career, director Infascelli worked as a production assistant and assistant director at American indie production company Propaganda Films. There, Infascelli apparently collaborated on music videos and commercials alongside Propaganda Films co-founders Dominic Sena and David Fincher. This is pertinent inasmuch as Almost Blue demonstrates a stylised “MTV aesthetic” similar to Sena’s debut feature, Kalifornia (1993), and Fincher’s sophomore film Se7en (1995), both of which focus—like Almost Blue—on the activities of serial killers. (The influence of Se7en has often been cited in discussions of other examples of the neo-giallo, including Dario Argento’s 2001 film Sleepless.)

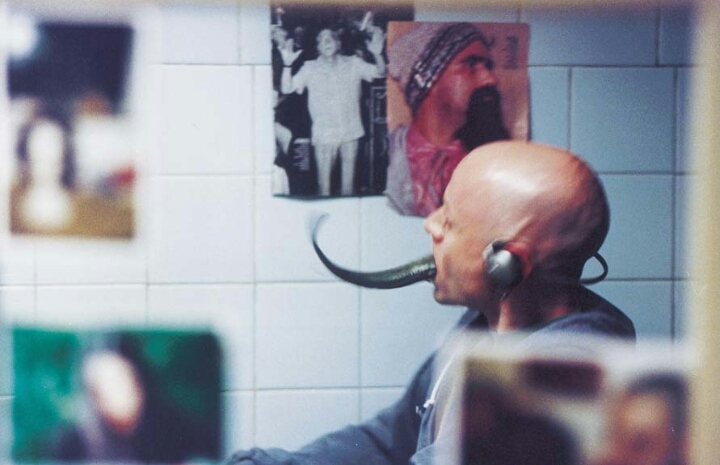

Like the aforementioned films by Sena and Fincher, Almost Blue’s adoption of the MTV aesthetic is demonstrated through the use of techniques which have become fairly commonplace in films since, including but not limited to: fast edits, canted angles, a drifting

camera accompanied by studiedly “spontaneous” compositions, and an elliptical approach to its narrative. In particular, the narrative of Almost Blue is punctuated by moments almost staged like self-contained music videos. In one of these, Alessio is shown alone, strobe lighting creating a disorienting effect as he mutilates his body at a sink, piercing his nipples and eyebrow to resemble his most recent victim whilst pounding techno music (sourced from the headphones that the killer constantly wears) plays on the soundtrack.

Alessio experiences auditory issues that mirror Simone’s blindness and synesthesia. In Lucarelli’s novel, chapters narrated by Alessio foreground the constant ringing of bells he hears, and which he attempts to assuage by listening to loud techno music through

headphones.

This isn’t articulated very clearly in Infascelli’s film adaptation, though throughout the movie we see Alessio wearing headphones; and there is a particularly memorable scene, presented in long-take and from Alessio’s point-of-view as he enters one

of his victim’s homes under false pretences, in which the techno music Alessio listens to constantly becomes a key part of the diegetic sound design. (The scene is particularly reminiscent of some of the iconic sequences in the films of Dario Argento in which the viewer is presented with extended point-of-view shots from the killer’s perspective, soundtracked by the music of Goblin, Claudio Simonetti, or pre-existing heavy metal tracks.)

With a lean running time of 85 minutes, Almost Blue’s narrative sometimes feels a little disjointed. In particular, Grazia’s complex relationship with her mentor Vittorio is condensed and presented in a particularly reductive manner. Little of this is present in Infascelli’s film, which posits Vittorio as a character who makes what is little more than a cameo appearance in a number of scenes. The film takes an already short novel and presents a much- condensed interpretation of its narrative. For what it’s worth, the aforementioned early script for the film, credited solely to Donati, has a page count of 106, and the structure is much more faithful to the source novel. That said, Almost Blue is a fascinating and pivotal example of the neo-giallo that underscores the relationship between the giallo and noir, its story examining a key moment in the development of our relationship with digital communications.

- Throughout the rest of this article, the giallo all’italiana will be referred to simply as giallo, in line with the use of the term by Anglophonic critics and fans to designate the specifically Italian-style thrillers produced predominantly during the 1960s and 1970s. (For Italian audiences, of course, giallo refers to a thriller of any designation, regardless of its context of production.)

- “a strange mechanical voice, asexual, emotionless, the same voice used for both interlocutors.”

Paul is a writer and lecturer from a working-class background in Lincolnshire, United Kingdom. Paul has written for a number of magazines and online publications, and has contributed chapters to several books and academic journals on topics such as Eurocult films about demonic possession, and American folk horror films. In addition, he has contributed research, booklet essays, and special features to boutique home video labels. His writing focuses predominantly on European popular cinema, crime fiction (particularly, neo-noir and the poliziesco), and horror cinema. He also writes fiction and occasionally makes short films.

Leave a comment