By Mo Moshaty

The ol’ bait and switch in horror films, particularly when it comes to the focus of the narrative, is a powerful storytelling device. It does a lot of heavy lifting in horror films as its main job is to subvert audience expectations and deepen the story, emotional and psychological beats, and impact. By presenting one character’s suffering as the central horror (often a vulnerable woman or a child) before shifting focus to another character’s internal struggle, the narrative expands beyond physical terror into existential and moral dilemmas. This shocking switch forces the audience to question where their sympathies lie and whether the true horror is supernatural or deeply personal. It also allows the horror audience to explore trauma in more complex ways, using one character’s suffering as a gateway to the broader themes of guilt, redemption, and sometimes, the limits of human power and control. Let’s take a deeper exploration of how this technique plays out in a whopper of a bait and switch in The Exorcist, and how it relates to the portrayal of internal struggle and emotional trauma.

In the context of The Exorcist, this bait and switch occurs when the audience is led to believe that Reagan’s possession is the central horror, only to find that the ultimate exploration is a deeper and more philosophical crisis: Is Father Karras a good human, and further, a good priest? His internal struggle with faith, guilt, and redemption becomes the sole focus. This shift in focus raises interesting questions on not only the narrative but the underpinnings of the film, specifically how trauma, especially a woman’s trauma, is framed and represented.

On the surface, The Exorcist seems to be a straightforward supernatural horror film about a young girl, Regan MacNeil (Linda Blair), who becomes possessed by a demon. The audience is immediately drawn into the visceral horror of Regan’s transformation, her violent outbursts, her disfigured appearance, and the terrifying supernatural occurrences surrounding her. The trauma inflicted upon Regan, both physical and psychological, is intense and serves as the primary narrative engine for the film’s early scenes. In this sense, the possession itself is the bait that attracts the audience’s attention. The horror is external, monstrous, and easily identifiable as “evil”. The expectation is that the film will revolve around Regan’s possession, her suffering, and the efforts of her mother, Chris (Ellen Burstyn), and the priests to save her. The audience anticipates an exploration of the supernatural and the horrors associated with it.

The Switch:

However, as the film progresses, the focus gradually shifts from Regan to Father Karras (Jason Miller), a Jesuit priest who’s struggling with his faith and the moral implications of his work. Karras’s internal crisis is deeply rooted in his guilt over the death of his mother, his doubts about his priestly calling, and his increasing despair over the seeming absence of God in the face of such suffering. This emotional and spiritual conflict becomes the central concern of the film, overshadowing Regan’s actual possession, trauma, and physical pain.

At the same time, Father Karras’s role in the exorcism is not one of simply saving Regan. Instead, it becomes more of a personal redemption arc: his confrontation with the demon mirrors his struggle to reclaim his faith, to come to terms with his past trauma, and to redeem himself through his actions. The possession in this sense becomes a backdrop to Karras’s transformation, and the film ultimately asks whether his willingness to sacrifice himself for Regan is an act of redemption or a sign of his brokenness.

Why It Works: It sucks putting a woman’s trauma aside for a man’s redemption arc (deep, spiritual sigh), but the bait and switch in The Exorcist elevates it beyond a typical possession film by shifting Regan’s physical suffering to Karras’s spiritual trauma, making his crisis of faith the film’s emotional core. While Regan’s possession is horrific, Karras’s struggle with doubt, guilt, and loss mirrors the isolation many trauma sufferers face. Framing the possession as a lens for exploring deeper existential fears, this shift introduces moral ambiguity: Should the audience sympathise more with Regan’s immediate suffering or Karras’s internal torment? By focusing on Karras, the film transforms into a psychological horror story where the true terror lies, not just in supernatural forces, but in the helplessness of a man who is supposed to wield faith as a weapon against evil. The film also reframes relational trauma, moving from Chris’s maternal love to care is his sacrificial role, underscoring how men in horror narratives often appropriate or become entangled in women’s suffering. Ultimately, The Exorcist uses Regan’s trauma as a metaphor for shattered belief, forcing the audience to question whether healing or redemption is ever truly possible. So, Blatty got his wish as The Exorcist was written on how to be a good Catholic.

At the start of Psycho (1960), the film appears to be centred around Marion Crane (Janet Leigh). A woman trapped by her circumstances who makes a desperate choice to steal $40,000 in hopes of starting a new life. The audience follows her closely: her anxiety, paranoia, and guilt building as she flees town and eventually seeks refuge at the remote Bates Motel. There she meets the awkward but seemingly harmless Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins), a young man dominated by his unseen, overbearing mother. The film carefully constructs Marion as its protagonist, leading viewers to believe that the story will revolve around her crime, her potential redemption, and the dangers she faces while on the run.

The Switch: In one of cinema’s most shocking twists, Marion is brutally murdered in the infamous shower scene, a mere 40 minutes into the film, completely upending audience expectations. What would initially seem like a crime thriller about a woman on the run instead becomes something far more sinister, an exploration of Norman Bates’s fractured psyche. With Marian gone, the narrative shifts its attention to Norman, gradually unravelling his deeply rooted psychological trauma, dissociative identity disorder, and the suffocating influence of his deceased mother. The film steadily reveals that Norman has been unknowingly operating under the persona of “Mother”, the domineering maternal figure who psychologically imprisoned him long before her death. Phew! I will interject here that there’s a strong mirroring between Norman’s parental oppression and suffering in Osgood Perkins’s work. But that’s another essay, and I’m not telling you anything you don’t already know.

Why It Works: The bait and switch in Psycho is so effective because it fundamentally alters the film’s genre and focus completely. Initially structured like a noir thriller, Psycho transforms into a psychological horror film, forcing its audience to engage with Norman’s deeply repressed trauma rather than simply following Marion’s escape. Hitchcock plays with audience sympathies, making them care for Marion’s fate and investing in her getting away with it, only to suddenly shift their emotional investment onto Norman, now a character of both menace and tragedy. The real horror of Psycho doesn’t lie in Marion’s murder itself, but in the revelation that Norman’s entire existence is dictated by his unresolved trauma, making him both a victim and a monster. The switch also redefines fear: what seemed like a random act of violence is actually the manifestation of years of repression, delusion, and the devastating impact of psychological control.

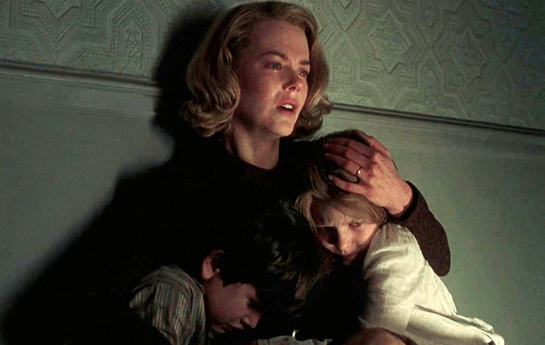

At first glance, The Others (2001) appears to be a classic haunted house story, one rooted deeply in Gothic tradition. The film introduces Grace (Nicole Kidman), a devoutly religious mother raising her two children in an isolated, perpetually shrouded mansion while awaiting her husband’s return from World War II. Her children suffer from an extreme sensitivity to light, forcing them to live in near darkness, which enhances the film’s eerie and claustrophobic atmosphere. As strange occurrences unfold, doors unlocking on their own, shadowy figures lurking, whispers in the walls, the film frames itself as a supernatural ghost story in which Grace and her children are at the mercy of whatever unseen forces seem to haunt their home.

Switch: As the film progresses, it methodically unravels its own premise, ultimately revealing that Grace and her children are not the ones being haunted; they are the ghosts. Spoiler! The figures they feared were not spirits intruding ontheir world, but the living residents of the house who are struggling to understand the supernatural presence lingering within their home. In a devastating realization, Grace remembers the truth: In a moment of despair, she killed her children and then herself when her husband did not return from war. The haunting, then, is not external but internal: the ghosts are trapped not by some external force, but by their own inability to accept death. The horror is no longer about supernatural entities invading their world, but about the devastating impact of denial, grief, and guilt. Heavy stuff.

Why It Works: The bait and switch in The Others is particularly effective because it subverts expectations of the haunted house genre while reinforcing its deeper, more emotional themes. Typically, ghost stories follow the living as they contend with spirits of the past. But in The Others, we’re reversed, centering on spirits who believe themselves to be alive. This inversion forces the audience to reconsider everything they know about the film’s reality, transforming what seemed to be a traditional horror narrative into a tragic exploration of psychological trauma and the denial of death.

Unlike conventional ghost stories that rely on jump scares or malevolent spirits or possession, The Others roots its horror in profound emotional suffering. The film becomes a meditation on guilt and the ability to move on, as well as the way trauma can trap individuals in a state of limbo, both metaphorically and in this case, literally. Grace’s strict adherence to her routines, her religious devotion, and her desperate attempts to maintain control over her environment all serve as manifestations of her psychological distress. This slow-burning tension builds not towards an external confrontation but towards an internal reckoning, making the revelation of her and her children’s situation all the more haunting.

Shifting the horror from external to internal, The Others elevates itself beyond the simple ghost story. It examines the lingering effects of grief and guilt, making the story not just about the supernatural, but the deeply human fear of facing one’s own actions and past.

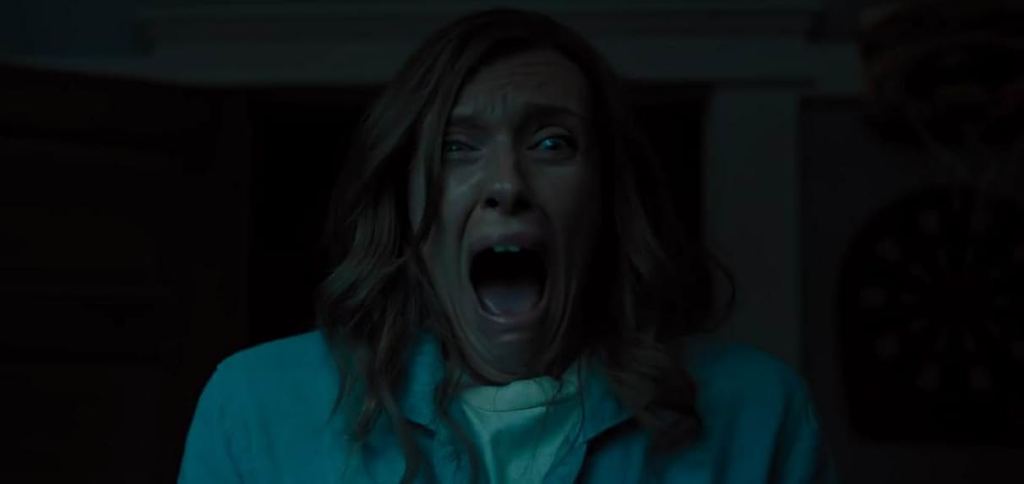

Hereditary (2018) begins with the grief and trauma of a family coping with the death of their matriarch, Ellen (Kathleen Chalfont). The film opens with Ellen’s daughter, Annie (Toni Collette), eulogizing her recently deceased mother, which immediately sets a tone of loss and emotional turmoil. The initial narrative leads us to believe that the horror of the film lies within the strange occurrences surrounding the family’s house and their mother’s secret of life. These include unsettling moments like the eerie doll house miniatures that seemed to mirror real-life events, strange noises, and disturbing visions. We also learn about Annie’s fraught relationship with her mother and her grief over the traumatic events in her life, including the loss of her own child many years ago.

The horror in the first act appears to be psychological, focusing on Annie’s unresolved grief, her strained relationship with her son Peter (Alex Wolff) and daughter Charlie (Milly Shapiro), and the question of whether the house itself is haunted or if the family members are being affected by some unseen supernatural force. This setup builds tension around the idea of familial trauma: the trauma caused by death, loss, and emotional scars left by generations of unresolved issues.

Switch:

As Hereditary progresses, the film takes a dramatic twist. It becomes clear that the true horror is not simply the supernatural occurrences within the house, but the legacy of generational trauma that haunts the family. What initially appeared to be a story about grief and psychological torment evolves into something far more sinister. The film reveals that the family’s trauma is not just a personal one, but rather something deeply entrenched in their bloodline involving ancient demonic forces tied to the death of Annie’s mother.

We learned that Annie’s mother, Ellen, was involved in a cult that worships the demon Paimon, a powerful and malevolent entity. It turns out that Annie’s grief and personal tragedies, the death of her son, the strange relationships, and the guilt she carries are directly connected to this family’s dark legacy. Her unresolved trauma becomes intertwined with supernatural events as the curse of this demonic force is passed down through generations. The film uncovers the horrifying truth that the deaths in the family, including the deaths of Annie’s late son and Charlie, are not mere accidents but part of a ritualistic process to summon Paimon and complete the demonic pact that has been sealed by their ancestors.

The twist of this generational curse is not only a shift from psychological horror to supernatural terror, but it also redefines the idea of inheritance. In the film, the trauma and suffering experienced by the family are not simply a matter of emotional scarring but have a much darker and more sinister foundation. The Bloodline would appear to be mere grief. Becomes an integral part of the family’s doomed fate.

Why It Works:

The bait and switch in Hereditary is particularly effective because of the way it lulls the audience into believing the story is one thing, only to reveal that it is something far more complex and horrific. The initial focus on grief and familial trauma resonates deeply with viewers as it taps into universal emotions and experiences. The film uses this emotional depth to create a sense of realism before introducing the supernatural elements, which makes the eventual reveal of the curse even more shocking.

The success of the bait and switch comes from the seamless transition between two types of horror: psychological and supernatural. The film explores how trauma can be passed down through generations and the idea that the family suffering is not just a result of personal misfortune, but a consequence of a dark inherited fate that gives the horror at depth that goes beyond Annie’s personal suffering. It becomes clear that the family is not simply being haunted by their own past but is trapped in a horrifying cycle of inherited pain and evil that spans generations. This realization creates an additional layer of horror, making the audience question whether escape from such a legacy is even possible. The bait and switch works on a thematic level as well. The film explores the complexity of family relationships, grief, and trauma while also delving into the darker themes of fate, control, and powerlessness. The supernatural elements are not just a backdrop for the psychological horror, but they serve to amplify the film’s exploration of how trauma is passed down, often without the knowledge of those who are doomed to inherit it. By the time the full extent of the family’s curse is revealed, it’s both terrifying and heartbreaking, making the audience reflect on how much trauma shapes lives in both visible and invisible ways.

Heredity plays on expectations, shifting the narrative from the grounded exploration of family trauma to a terrifying supernatural tale that reveals much more insidious and intergenerational horror.

At first glance, The Witch (2015) presents itself as a traditional supernatural horror film, drawing on the familiar trope of a family being haunted by a malevolent witch. Set in 1630s New England, the Puritan family lives on the fringes of a dense forest. Isolated. From the nearby colony. The early signs of trouble include the family’s failing crops, mysterious and unsettling events surrounding their livestock, and the sudden disappearance of their youngest son, Sam. These events create an atmosphere of palpable dread as the family grows more paranoid and suspicious of each other.

The initial narrative seems to follow the familiar pattern of witchcraft horror, where the family’s misfortunes are attributed to the supernatural presence of a witch or something similar, lurking somewhere in the wilderness. The eerie images of the woods and the frightening figure of the witch (who we first see as an old woman performing stage rituals) lead the viewer to believe that the true horror is supernatural, a malevolent force using witchcraft to prey on the family. Natch.

This sets the audience up with the classic horror premise: a family, a mysterious witch, and the threat of an. Evil power beyond their control. A tale as old as time. The viewer expects the narrative to follow the traditional trajectory of witch hunting, where the family must struggle against an unseen or threatening supernatural force that either leads to their downfall or, in some cases, the triumph of good over evil.

Switch:

As the film progresses. We shift focus, and the audience realises that the true horror is not only the supernatural presence of the witch, but the deep psychological and emotional unravelling of the family, particularly that of the protagonist, Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy). While there are certainly supernatural events at play, the film delves into much darker themes, including the families, oppressive religious dogma, the internal tensions that drive them apart, and most significantly, the psychological disintegration of Thomasin as she is forced to confront her own identity, desires and the pressures of societal expectations, because the suppression of women’s desires always works out, right?

The film slowly reveals that the family’s misfortunes are exacerbated by the rigid puritanical beliefs. The father, William (Ralph Ineson), is depicted as increasingly strict and obsessed with his own perceived moral righteousness, while the mother, Catherine (Kate Dickie), is consumed with guilt and paranoia over their situation. These characters’ rigid views create an emotionally toxic environment where blame is easily placed on external forces, such as witches, rather than acknowledging the internal fractures within the family structure.

Further into the film, Thomasin becomes the focus of the narrative. Her growing awareness of her sexuality and her burgeoning desire for freedom from her family’s oppressive expectations are explored as key themes. The witch, in this context, is revealed to be less of an external threat and more of a metaphor for Thomasin’s sexual awakening and her rebellion against the societal and religious constraints that have defined her entire life. The witch’s presence in the film mirrors Thomasin’s struggle to define herself and embrace individuality outside of the rigid structures imposed on her.

The twist of the film is not just about revealing the true nature of the witch, but showing how the witches influences tied to Thomasin’s own journey. By the end of the film, Thomasin’s interaction with the witch and her ultimate decision to join the coven become symbolic of her rejection of the repressive world and stepping into freedom. The witch, in this sense, represents both the temptation of freedom and the cost of embracing one’s true nature in a world that punishes such desires.

Why It Works:

The bait and switch in The Witch works because it subverts the traditional witchcraft narrative by shifting the focus from external supernatural forces to the deeply internal and psychological struggles of the characters. The film’s strength lies in its slow, deliberate exploration of isolation, religious extremism, and the unravelling of family dynamics, all of which contribute to the unravelling of Thomasin’s psyche.

We begin with the appearance of a typical witch horror story, but as it deepens, it reveals itself to be a much more layered exploration of human desire, repression, and personal identity. The shift from supernatural horror to psychological horror is seamless and reflects a larger thematic concern with the dangerous, unchecked faith in the oppressive systems that control individuals, particularly women.

By positioning the witch as both a literal figure in the story and a metaphor for Thomasin’s sexual and emotional awakening, the witch becomes more than just a simple tale of witchcraft. The witch represents the freedom Thomasin seeks, a freedom that her rigidly religious family cannot comprehend or allow. The film shows how the pursuit of this freedom can lead to self-destruction, but also to self-empowerment and transformation. In this way, the bait and switch amplifies the horror of the story, not just by revealing a supernatural threat, but by showing how deeply the family’s beliefs, fears, and guilt are embedded in Thomasin’s journey. The witch becomes a symbol of both danger and liberation, and Thomasin’s eventual choice to embrace her own desires marks her break from the toxic family dynamic, illustrating the cost of rejecting conformity and embracing one’s true self. This shift makes the horror of the witch not just about witches, but about how society polices the desires and identities of its most vulnerable members, especially women.

Check out more bait and switch films here!

Leave a reply to THE DEVIL IN THE DETAILS: THE REAL EXORCISM BEHIND 2025’S ‘THE RITUAL’ – NightTide Magazine Cancel reply