By Mo Moshaty

Mother daughter relationships are often characterized by intense emotional connections shaped by love, care, and expectations for horror films, they highlight these dynamics by. Emphasizing counts arising from a mother’s overprotectiveness or a daughter’s struggle for independence. Movies like Pearl and Black Swan portray a mothers attempt to shield or control her daughter, leading to intense power struggles that mirror real life familial tensions.

Many women experience unresolved issues passed down through generations, including societal pressures, body image concerns and self-worth struggles. Horror often internalizes these psychological battles. In Pearl, the trauma transmitted from mother to daughter manifests was literally and physiologically underscoring how trauma can haunt families, especially within a matriarchal lineages. A mother’s influence plays a significant role in shaping our daughters identity. However, as daughters grow, they frequently challenge these imposed identities. Horror cinema explores this quest of autonomy through supernatural or psychological lenses, portraying daughters struggling to break free from their mother’s shadow as a symbol of personal emotional growth. The horror genre amplifies fears of becoming like one’s mother or of losing one’s identity entirely. Mothers are traditionally associated with childbirth and caregiving, linking them to themes of bodily autonomy and control. Films such as The Babadook and Rosemary’s Baby depict the horrors of motherhood as a loss of control over one’s body and mind. These stories parallel life anxieties about post-partum depression, societal expectations, and the physical demands of motherhood. Women on face societal pressures to embody idealized versions of motherhood, nurturing and femininity. Horror films exploit these expectations by depicting mothers who fail to conform to these norms, as seen in The Others or daughters who reject these constraints, exposing the fear of judgement, failure, and rebellion against tradition.

The film Pearl (2022), directed by Ti West, serves as both character study and a horror exploration of repression, ambition, and unchecked madness. Starring Mia Goth in the titular role and Tandi Wright as her formidable mother Ruth, Pearl delves into the toxic power dynamic and domineering mother and a daughter yearning for escape. Set against the bleak backdrop of World War I and the Spanish flu pandemic, Ruth, a stern German immigrant, imposes strict discipline upon Pearl, hoping to protect her from life’s disappointments.

However, Pearl’s artistic aspirations and deep seated desire for adoration clash violently with her mother’s pragmatism. Ruth’s trauma is deeply tied to the struggle of maintaining a household and caring for her disabled husband amid wartime scarcity. Her harsh demeanor is not born out of malice, but out of fear. Fear that Pearl will be crushed by the world if she’s not sufficiently hardened. Pearl, on the other hand, internalizes this control as an oppressive force, preventing her from achieving greatness. Goth’s performance embodies Pearl’s desperation, swinging between wide-eyed innocence and unsettling malevolence, making her one of the most captivating horror protagonists in recent memory. Pearl’s suppressed emotions, coupled with her unfulfilled ambitions, ultimately lead her down a violent path. The film highlights how generational trauma can manifest in destructive ways, with Ruth’s attempts at control backfiring spectacularly. The climactic confrontation between mother and daughter is both tragic and terrifying, illustrating how repression, when left unchecked, can transform into something monstrous. Let’s not forget that haunting, unbroken end-credits smile; Mia Goth’s masterclass at simmering madness that echoes.

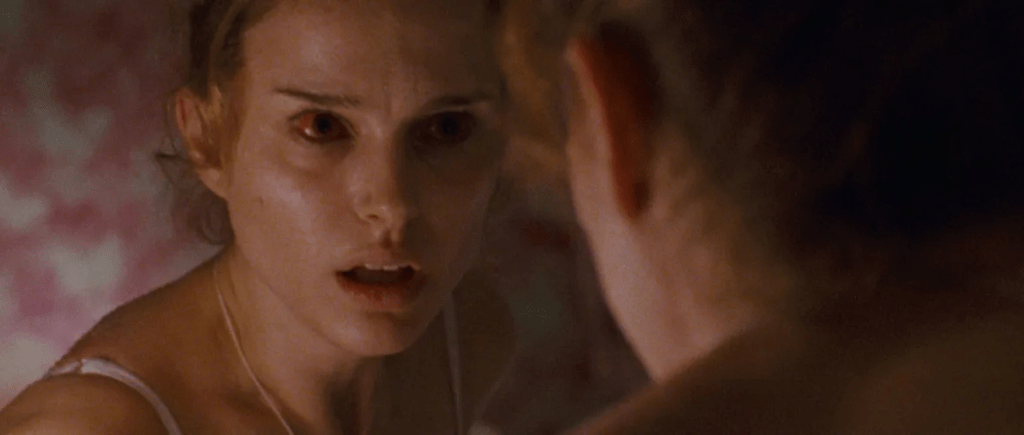

Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan (2010) is often perched as a psychological horror film, but it’s also a deeply unsettling character study that explores the devastating effects of maternal trauma, perfectionism, and identity crisis. Starring Natalie Portman as Nina Sayers and Barbara Hershey as her overbearing mother Erica, the film paints a harrowing portrait of a young woman pushed to the brink of madness. While the world of ballet is already notorious for its punishing physical and emotional demands, Black Swan goes further, showing how Nina’s fragile psyche is shattered under the weight of her mother’s control, artistic obsession, and internalized repression. With its psychological intensity, body horror elements, and powerhouse performances, Black Swan stands as one of the most compelling cinematic depictions of generational trauma through vicarious living.

At the heart of Black Swan lies the relationship between Nina and her mother, Erica. Erica is former dancer whose own career aspirations were cut short. Instead of dealing with her unfulfilled dreams in a healthy way, she projects them onto Nina, molding her daughter into perfect ballerina she never got to be. But this isn’t just the classic case of a stage parent pushing their child into success, it’s something far more insidious. Erica’s obsession with controlling every aspect of Nina’s life creates a suffocating dynamic in which Nina never truly develops a sense of autonomy. Erica infantilizes Nina, treating her as though she’s still a little girl. From the pink doll filled bedroom to the way she tucks Nina in at night, Erica keeps her daughter trapped in a state of arrested development. Nina’s world outside of ballet is practically nonexistent, and any hint of independence, like her attempts to explore her sexuality or connect with other dancers, is met with Erica’s disapproval or outright hostility. In one particularly unsettling scene, Erica bursts into Nina’s bedroom to stop her from masturbating as if her daughter’s own body doesn’t belong to her. This extreme control manifests in Nina’s psyche as guilt, fear, and a pathological need to please her Mother no matter what the cost.

The world of ballet demands perfection, and Nina embodies this idea ideal to a disturbing degree. She’s disciplined, technically flawless, and utterly dedicated to her craft. But perfection comes at a cost. Nina is so obsessed with getting everything right that she lacks passion, spontaneity, and self-expression, qualities essential for dancing the role of the Black Swan in Swan Lake. This is where Lily (Mila Kunis) comes in as Nina’s foil. Unlike Nina, Lily is effortless, seductive, and unrestrained, embodying the confidence and freedom that Nina lacks. She represents the Black Swan in its purest form, something Nina both fears and desires. As Nina’s paranoia spirals out of control, blurring the lines between rivalry, attraction, and self-destruction, Erica’s role in this self-destruction cannot be overstated. Her rigid expectations reinforce Nina’s belief that anything less than perfection is a failure. This is one of the film’s most terrifying insights: perfection is not a goal, it’s a prison. Nina, like so many women who struggle under the weight of impossible parental expectations, does not know how to escape it. Instead she internalizes the pressure by pushing herself past her physical and mental limits in pursuit of an ideal that is, by all definition, unattainable.

One of Black Swan’s most brilliant aspects is its use of body horror to externalize Nina psychological breakdown. As her mind fractures under the pressure, so does her body – at least in her perception. She see disturbing hallucinations: her reflection moves independently, her skin peels away, and black feathers begin to sprout from her body. These grotesque transformations symbolize Nina’s loss of self as she becomes consumed by the role of the Black Swan. It is not just a metaphor for artistic obsession but also a reflection of how trauma manifests physically. The mind and body are not separate entities; they are intertwined and when one suffers, so does the other. Erica’s presence in these moments is both literal and symbolic. She lurks at the edges of Nina’s delusions, embodying both the pressure to succeed and the fear of failure. In a key scene, Nina hallucinates a version of herself transforming into a monstrous swan with red eyes and black feathers bursting through her skin. This transformation is horrifying, but it’s also freeing. For the first time, Nina let’s go of control, embracing the chaos and sensuality she has long suppressed. But at what cost?

The climax of Black Swan is one of the most haunting sequences in modern horror. As Nina takes the stage, she fully embodies both the White and Black Swan, delivering the performance of her life, but in doing so she loses herself entirely. The transition is complete: she has become the Black Swan, but she can never return to who she was before. The perfection she has spent her life chasing is, paradoxically, what destroys her. Her final words, “I was perfect,” are chilling. They are not spoken with joy, but with tragic finality. Nina has achieved what her mother always wanted for her, but in the process, she has erased herself. And Erica? She is left screaming in horror, finally realizing that her daughter’s perfection was nothing more than a beautiful death.

Black Swan is a film about ambition, artistry, and psychological unraveling, but at its core it’s a film about the horror of maternal control and instructive pursuit of perfection. Erica’s suffocating influence on Nina is not the story of a controlling mother, it’s the story of countless women who have been told they must be flawless to be worthy. It asks us to consider what we sacrifice in the pursuit of greatness and whether perfection is ever truly worth the price. For Nina, the answer is clear, she may have achieved her dream, but she didn’t survive it.

Kate Dolan’s 2021 psychological horror film You Are Not My Mother takes the familiar trappings of the horror and weaves into an intimate meditation on mental illness, national trauma, and the bond between mother and daughter. Starring Hazel Dupe as Char and Carolyn Bracken as Angela, the film explores how the horror of the supernatural and the horror of a fractured family are often indistinguishable from one another. It’s a film about slow unraveling of trust, the terror of change, and the fear that those closest to us might not be who we think they are.

At the center of You Are Not My Mother is the fraught relationship between Char and her mother, Angela. Angela is introduced as a woman weighed down by the crushing burden of depression, barely present in her own life, let alone Char’s. She spends much of her time in bed, withdrawn from the world and unable to provide the emotional support Char desperately needs. Their household is one of eerie silence and suppressed pain, where Char must navigate adolescence without a stable parental figure to guide her. Then Angela disappears, and when she returns, something is drastically different.

Bracken’s performance as Angela is masterful in its subtlety. Before her disappearance, she moves with the heaviness of someone carrying an unbearable weight. When she returns, she is different, lighter, more vibrant, but also eerily unpredictable. Her sudden shift from distant and depressed to unnervingly affectionate is both a relief and cause for alarm. Char, played with quiet intensity by Doupe watches her mother with growing suspicion, torn between wanting to believe in this newfound warmth and fearing the uncanny wrongness that lurks beneath it. This is where You Are Not My Mother excels: the horror is not just in what Angela might become, but the idea that this change, this terrifying instability, is something Char has always had to live with.

One of the most unsettling aspects of the film is how it mirrors the real life experience of living with a parent who struggles with severe mental illness. Before Angela disappears, she is already a ghost in her own home, retreating from Char and leaving her daughter in a perpetual state of uncertainty. Will today be a good or a bad day? Will she be able to function or will she be swallowed by her illness? These are the kinds of questions children of mentally ill parents often struggle with and Char’s hesitance around her mother, her constant bracing for the worst, feels heartbreakingly real.

When Angela returns, that unpredictability is amplified. She’s suddenly engaged, full of energy and at times almost too affectionate. But this shift feels unnatural, like a pendulum swinging too far in the opposite direction. The film taps into the fear that a loved one can become unrecognizable, whether from illness or something supernatural. This transformation in Angela is both terrifying and tragic. She is the mother that Char desperately wants back, but she is also something that Char can no longer trust. Is this the heightened metaphor for the cycles of mental illness, the highs and lows, the moment of clarity followed by complete collapse? The film refuses to offer any easy answers, forcing the audience to sit with the discomfort of the unknown.

While You Are Not My Mother works as a psychological horror film, it’s also deeply rooted in Irish folklore, particularly the legend of changelings. The idea that a loved one, especially the mother or a child, can be taken and raised by something inhuman, is a longstanding myth. These tales were often used to explain any shifts in personality, developmental disorders, or mental illness, attributing them to supernatural interference rather than natural causes. In the film, Angela’s transformation aligns with the traditional changeling narrative. Her family, particularly Char’s grandmother Rita (Ingrid Craigie), seems to know more than she lets on. There are hints that this has happened before, that Angela’s struggles are not just personal but generational. The suggestion that this is part of a cycle, a curse even, adds another layer of horror. This generational aspect is crucial. Char is not just fighting to understand what is happening to her mother, she is also fighting to break free from a cycle of trauma that has shaped her entire family. She is caught between wanting to save Angela and needing to save herself, a conflict that many children of struggling parents will recognize.

On top of everything happening at home, Char is also dealing with the cruelty of adolescence at school. She is bullied and ostracized, making her mother’s instability more isolating. She has no real support system outside of her family, no safe place to turn when things start to unravel. Even if she tries to understand what’s happening to her mother, she’s also fighting to carve out a space for herself in an environment that offers absolutely no kindness. This aspect of the film speaks to a broader experience: the loneliness of growing up in a family where the parent-child dynamic is reversed where the child must become the caretaker. Char is forced to be more responsible than any teenager should have to be, and the weight of that responsibility is palpable in every scene.

As the film reaches its climax, the supernatural and psychological elements collide in a way that is both terrifying and cathartic. Char is forced to confront not only what her mother has become, but also the truth about their family’s past. The final act of the film is a master class in slow burning dread giving way to explosive horror. It is not just about survival, but about recruiting agency, about deciding whether to perpetuate the cycle of trauma or to break it. It’s about love and loss, fear and resilience, and the terrifying realization that the people we love most can also be the ones who hurt us the deepest.

Dolan’s film is a reminder that horror is at its most powerful when it speaks to real experiences. By blending folklore with psychological horror, You Are Not My Mother creates a chilling and deeply personal exploration of what it means to love someone who is slipping away.

Horror cinema has long been a vessel for exploring the fraught and often painful dynamics between mothers and daughters. The mother-daughter bond, already complex, becomes even more terrifying when amplifying supernatural elements or psychological instability, exposing the raw vulnerabilities of both figures. These narratives highlight a universal truth: people we love the most can be the source of our deepest suffering. Yet in these nightmarish depictions, there is also a form of catharsis, an acknowledgement of generational wounds and the possibility of breaking cycles of pain. Whether through rebellion, revenge, or tragic self-destruction, horror’s mother-daughter stories force us to confront the weight of familial expectations, and the scars left behind. As the genre continues to evolve It remains one of the most compelling spaces to explore the fears, failures and fierce love that define these relationships, proving that sometimes the most haunting ghosts are the ones we inherit.

Leave a comment