By Avery Coffeey

Our earliest example and experience of companionship is, traditionally, our parents. We’re intended to learn the intimate and nurturing nature of close bonds in their purest form. Yet, some parents create life out of ego. The story of Frankenstein, as we know it, depicts Victor Frankenstein’s childhood as safe and gentle. That’s not the version I wish to discuss. Guillermo del Toro’s take on the classic Gothic story delivers an offspring fueled by rage towards generational trauma. Inspired by his own self-reflection, del Toro expands upon Mary Shelley’s original nature versus nurture theme using oppressive systems, like rigid masculinity and religion, as pillars for the neglect that Frankenstein’s creation faces. He does away with the idea of revenge for rage and forgiveness to coexist in honor of justice.

Parenthood has always been treated like a milestone of success for heteronormativity. However, maybe it wouldn’t be if the need to reproduce wasn’t reinforced in our society for centuries. Frankenstein (2025) takes place during the Gilded Age, when having a child wasn’t about wanting one but needing one. That’s why Victor feels closest to his mother, though. Their relationship was fostered by emotion, whereas his relationship with his father was fostered by logic. Men shouldn’t have emotions, so the patriarchy says. They bond over education and the future that Leopold Frankenstein sees for his son. He tells Victor, “You bear my name and, with it, my reputation,” after giving him lashings for a wrong answer during their one-on-one medical lesson. Victor is probably 13 or 14 years old, and he already feels the weight of his father’s responsibilities.

The legacy that he’s expected to uphold is tainted in the wake of his mother’s death. According to Victor, his father failed by not saving his mother’s life during childbirth. He vows to be better than his father in the same way that a child does after facing their parent’s rage. So Victor carries his disdain for Leopold into his adulthood as he tries to make discoveries that his father wouldn’t dare traverse. It persuades the audience to empathize with Victor early; washing Oscar Isaac with a ring of light (like a halo) as he’s condemned for his ambitious medical practices. He passionately preaches about his experiment, and you, as the audience member, really admire his passion. Frankenstein’s pursuit of revolution is soon overrun by his ego, though. Just like his father, he craves a kind of control that only rots the living around it.

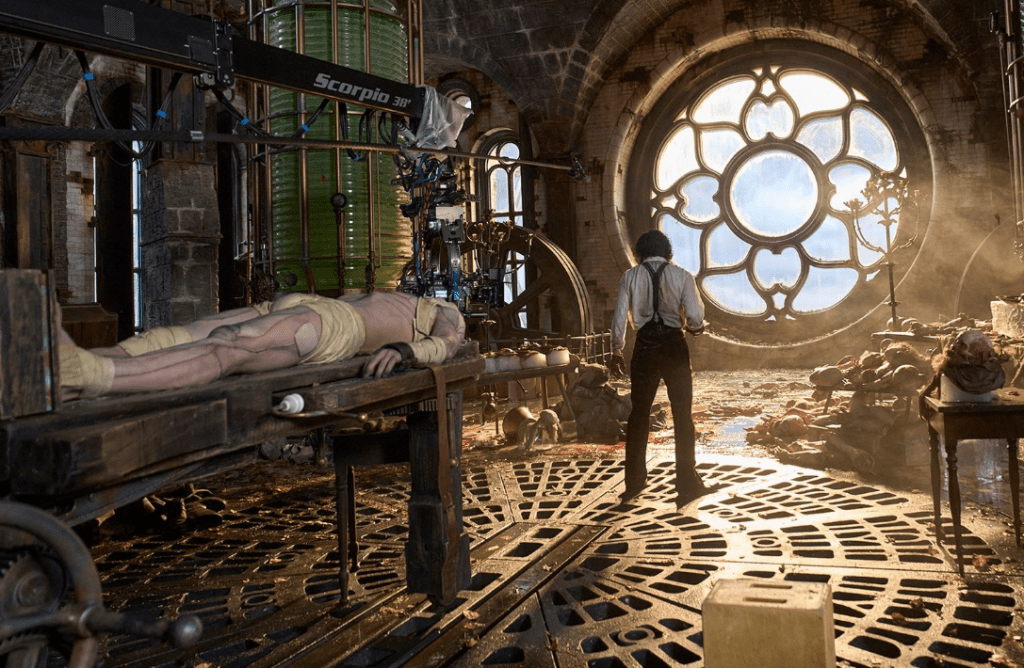

The Creation’s first interaction with Victor is warm and bright: mostly because of the sun. The mad scientist repeats this noun while teaching his experiment that it’s not something to fear. He leans into the creature’s chest to hear his heartbeat and loosely drapes his arms around Victor. This bareskinned hug lights a fire that Victor eventually extinguishes. He manipulates the Creature into imprisonment, and his narration says, “having reached the edge of the earth, there was no horizon left,”. This feeling grows with his impatience towards his creation after every failed attempt at making a show pony out of Jacob Elordi’s character. Frankenstein begs him to say something other than his name, but the doctor hasn’t taught him any other words. Of course, he takes after his father in cruel punishment with whippings for imperfection.

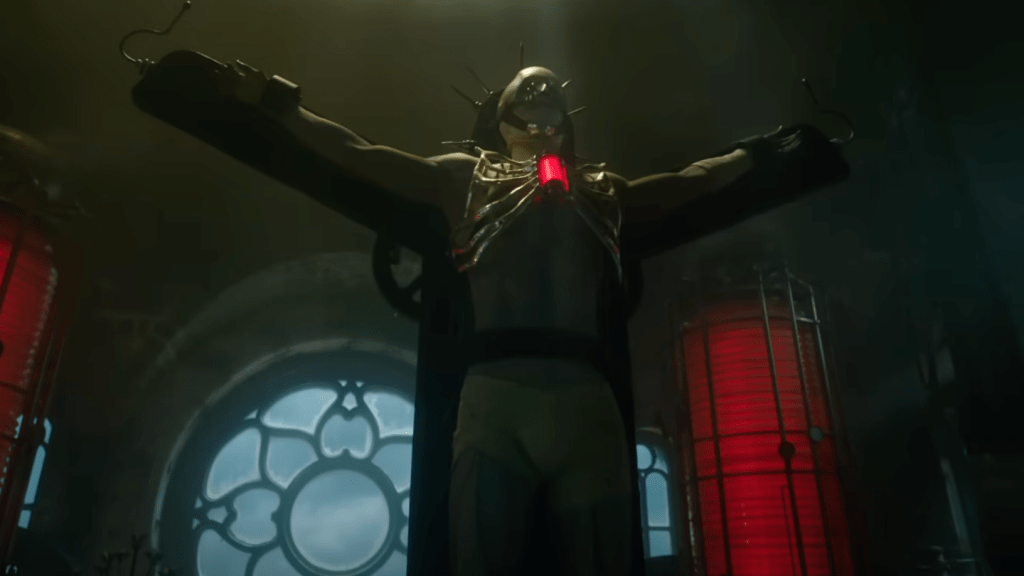

The movie is about ego, shame, and forgiveness in three acts. Victor realizes he can’t extend his ego through his own creation like his father, and falls into a pit of regret. Tallying his sins, the Catholic guilt weighs on him, but he thinks he can outrun it. He was raised with a religion that instills the power of fear rather than life after all. Victor’s father exploited that power, but the doctor can’t do the same for his creation. What does he have to stand on without the socialization that reinforces docility? Del Toro emphasizes the difference in size between the Creature’s hulking frame and Frankenstein’s average human stature to remind viewers that Victor’s power is an illusion created by ego. He has to chain his experiment, almost like clipping his wings, to keep it under his oppressive rule.

The Creature discovers his own power in the wake of Victor’s evasion: both physically and emotionally. In the absence of his maker’s religious and patriarchal influences, Frankenstein’s creation is informed of the world, himself, and his father through the love he observes in the old, blind man. This love isn’t influenced by religion but, rather, humanity. See, del Toro doesn’t wish to persuade viewers away from religion. John Milton’s Paradise Lost is a cited material that the old man introduces to the Creature. Without the precontext of the Bible, he identifies with Satan as a rejected being and with Adam as the first of his kind. The sympathetic lens offered to both God and Satan in that epic poem lends itself to his own perception of the relationship that he and his maker share.

There comes that time in all of our lives when we see our parents for more than their relationship to us. How do you set aside the trauma inflicted to acknowledge theirs? Well, the Creature doesn’t. Not at first. Their cat-and-mouse chase ends when Victor realizes that he’ll always be backed into a corner by the immortality of his own creation. His feelings of remorse aren’t inspired by the Creature at first. But, with no one left in his life, he finds that the hole in chest remains. In the end, the true power that the Creature exerts over his maker is sympathy and forgiveness: two things Victor wasn’t capable of. Yet he learned more in his dying hours from his offspring than he did from his own father.

This is how I imagine the conversation that the director mentions between himself and his late father. I imagine that’s how a lot of us feel, processing our parents’ trauma with our own. We may spend months or years holding a grudge against those who brought us into this world. The guilt might only anchor them to the surface of accountability. And though the Gilded Age is far behind us, some of its oppressive systems still corrupt family ties. Fathers still repress their trauma in the name of the patriarchy, but films like Guillermo del Toro’s spark the conversations needed to break through those barriers. Breaking the cycles of abuse and trauma starts with the acknowledgement exhibited in the end of the film. Victor’s creation once believed that violence must be inevitable between those hunted and those who hunt. But in realizing that it doesn’t have to be that way, he dismantles those pillars that tried to suppress his sovereignty.

Leave a comment