By Jonathon Greenall

1932’s The Mummy is one of the most fascinating pre-Code horror films. Despite not being as popular or fondly remembered as Dracula or Frankenstein, The Mummy is one of the most important works in film history, as it spawned a whole new subgenre of monster movies. However, this wasn’t the only way The Mummy innovated. Due to its visual language and the unique handling of its core story, The Mummy is also an early example of (unintentional) queer themes and coding in Hollywood horror cinema. Thus, it laid the foundation that James Whale and numerous other artists would build upon, creating modern queer horror as they did.

It shouldn’t be surprising that a movie designed to cash in on the pop culture frenzy surrounding the 1922 discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb (and the numerous “Curse of the Pharaohs” myths it spawned) would end up evoking ideas of queerness as part of its narrative. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Ancient Egyptian narratives provided a space where the usual roles of society could be inverted or ignored, allowing people to imagine and enjoy ideas that contradicted their era’s moral norms and values.

In her now-legendary 1998 essay, Consuming Bodies: Cultural Fantasies of Ancient Egypt, Lynn Meskell notes that “the shifting sexualities of the Egyptians have been employed as a parallel for our own experiences, with little need for ancient evidence,” going as far as to say that “many constructions of Egypt have also been queered,” as they frequently focus on characters whose sexual practices exist in opposition to the norm, even though we have little evidence that such practices occurred during the era.

Hints of this view of Ancient Egypt appear as early as the movie’s first scene. While theorizing why Imhotep was mummified alive, Ralph Norton jokingly suggests the punishment was because “he got too gay with the vestal virgins in the temple.” While this movie predates the modern use of gay (and the joke is based on heterosexual relations), the fact that the film so quickly and casually seeds the idea of Ancient Egypt being a place of transgressive sexuality shows how Ancient Egypt was seen in the era, a perception that informs the entire film’s approach to its central conceit.

However, culture shock over the film’s handling of Ancient Egypt won’t be the first thing modern viewers notice about The Mummy. Despite being considered the film that cemented the mummy as a monster movie archetype, 1932’s The Mummy features practically none of the tropes we now associate with the genre. Unlike later mummy-focused horror films, which spend most of their runtime showing bandaged monsters chasing plucky heroes through decaying tombs, The Mummy only shows Imhotep in his mummy form twice: during the opening scene, where his casket is first discovered, and at the end of a flashback sequence, where Imhotep explains how he ended up in the previously-seen casket.

Instead, Imhotep spends the vast majority of his screentime in disguise as historian Ardath Bey, wandering through museums and the homes of wealthy academics. This decision leads to one of The Mummy‘s most notable queer themes: the struggle for identity and the pain of trying to exist in a world that refuses to accept you.

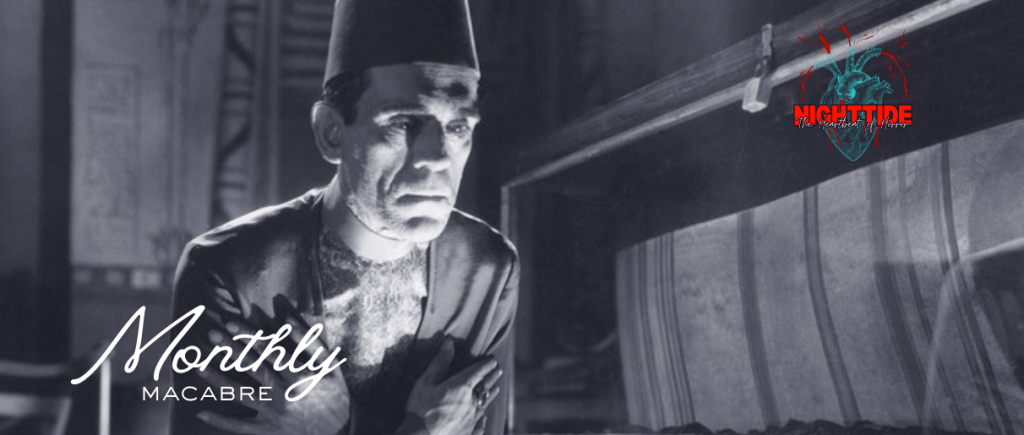

It is impossible to watch the scenes where Imhotep poses as Ardath Bey without noticing the immense discomfort he radiates. Much of this discomfort comes from Boris Karloff’s body language. When playing Ardath Bey, Karloff maintains a painfully stiff posture, something that makes him tower over the film’s other characters. Combine this with his slow, often unnatural movements, and Ardath Bey is always surrounded by a tense, uneasy aura. This only intensifies when he shares the screen with the human characters, as their more natural body language further accentuates Karloff’s inhuman performance.

However, this awkwardness isn’t just due to Karloff’s physicality. His social interactions also display that, despite his best attempts to embody a man of the era, Imhotep is never able to fully embrace his mask.

This is best seen when Imhotep first meets Sir Joseph Whemple in the Cairo museum. When Whemple offers his hand to Imhotep, Imhotep looks at it quizzically rather than shaking it. When they converse soon after, Imhotep responds to all of Whemple’s questions with short, sharp statements before fragrantly breaking social norms by bluntly rejecting an offer of hospitality, leaving Whemple and his son confused and suspicious, something that eventually leads to Imhotep’s downfall.

It should be noted that this awkwardness would be more pronounced for contemporary viewers. Not only does The Mummy share numerous story beats with Universal’s 1931 film Dracula, but several members of Dracula’s cast return in The Mummy, playing similar roles. For example, David Manners (who was Jonathan Harker in Dracula) plays the heroic love interest, and Edward Van Sloan (Dracula’s Van Helsing) takes the wise older mentor role. Thus, viewers at the time would naturally compare Imhotep to Dracula, something which makes Imhotep’s social failures all the more obvious. Because, while Dracula was able to integrate himself into London high society without issues, Imhotep struggles to engage in simple small talk without making it obvious he isn’t all he seems.

This queer struggle for identity isn’t restricted to Imhotep either. In the latter half of the film, after Imhotep awakens the memories of her previous life, Helen Grosvenor finds herself fighting over her body with the spirit of Princess Ankh-es-en-Amon.

When trying to explain her confusion and inner conflict, Helen opts to compartmentalize her psyche, describing her usual thoughts and her desire to obey Imhotep as if they were separate beings. For example, while recovering from an encounter with Imhotep, she tells Frank:

“There’s death there for me, and life, something else inside me that isn’t me. But it’s a life torn fighting for life. Save me from it, Frank, save me.”

A few scenes later, while talking to Dr. Muller, she notes she doesn’t want to give up fighting Imhotep’s control because:

“But I don’t want to lose my own mind, and be someone else, someone I hate!”

This struggle for identity complements one of The Mummy’s fascinating elements: its sympathetic portrayal of Imhotep. While Imhotep is undoubtedly the film’s villain, director Karl Freund went out of his way to portray him as a tragic figure.

Imhotep’s desire to take control of Helen Grosvenor and murder her so that Princess Ankh-es-en-Amon can live again is portrayed as an unequivocally evil action. However, the extended flashback sequence cements Imhotep as a man who became a monster due to tragic circumstances rather than someone who was naturally evil from the moment of their birth.

This sympathetic nature is only enhanced by the fact that Imhotep’s original death is by far the most violent and harrowing moment in the entire film. When Imhotep murders someone, he does it by inducing a heart attack, causing the victim to quickly and bloodlessly crumple to the ground. When Imhotep himself is sentenced to death, viewers are treated to an extended scene where he is mummified alive, during which Imhotep violently thrashes against the tightening bandages as the camera remains focused on the look of pure terror in his eyes, meaning that even the most stone-hearted viewer will feel at least a little pity for him.

So, while Imhotep’s relationship with Princess Ankh-es-en-Amon is firmly heterosexual, its tragic nature, combined with the vicious punishment Imhotep received for trying to prolong it, paints the relationship as inherently transgressive. Thus, it can be read as queer-coded (especially if you subscribe to David M. Halperin’s 1995 definition of queer that describes queer as something that “acquires its meaning from its oppositional relationship to the norm” and is “whatever is at odds with the normal, the legitimate, the dominant.”)

Viewed through this lens, Imhotep’s situation doubles as a metaphor for another common queer fear: disownment and social exile. Unlike Frankenstein or Dracula, who were slain by random people, Imhotep’s original death came at the hands of Princess Ankh-es-en-Amon’s father. Not only does this make his death feel even more violent, but it also captures the rage and rejection that many queer people encounter when they try to live as their authentic selves.

This theme is reinforced by the film’s recurring motif of grave desecration. In the opening scene, Dr. Muller notes that the “sacred spells that protect the soul on the journey to the underworld” were chipped off Imhotep’s casket, meaning he was “sentenced to death not only in this world, but the next.” Similarly, while telling Helen about Princess Ankh-es-en-Amon, Imhotep explains that not only was he buried alive, but once the grave was sealed, the pharaoh had the slaves killed and then executed the soldiers who did the deed so “no friend could creep to the desert with funeral offerings for my condemned spirit.”

When these elements are combined, they perfectly capture the sentiment that many queer people wrestled with during the 1930s. Having to question if the joy of living as one’s authentic self was worth the risk of family exile and banishment from public life. Something that makes Imhotep’s declaration that he can only be reunited with Princess Ankh-es-en-Amon when she is “ready to face moments of horror for an eternity of love” all the more relatable.

The Mummy is a fascinating film that feels vastly different from both the other pre-Code Universal horror films and the numerous Mummy films that would follow it. While likely unintended by the film’s producers, the story’s handling of Imhotep’s doomed romance with Princess Ankh-es-en-Amon radiates queerness, tapping into several anxieties queer people struggle with in both the 1930s and modern day. Thus, The Mummy acts as a powerful reminder that neither the silence of the grave nor a sealed casket can erase queer identity.

Leave a comment