By Mo Moshaty

We know what survival costs. The question is, who gets to be seen doing it?

The Final Girl has long been mythologized, studied, adored, endlessly replicated. She’s the white-hot core of slasher cinema, the trembling heartbeat that somehow outlasts the monster. But too often, she’s also white by design.

When horror scholars coined the term, they meant the Laurie Strodes, the Nancy Thompsons, and the Sally Hardestys. The virginal suburban survivors who made fear palatable and purity profitable restored order. Their blood sanctified morality, and their skin, of course, made both believable.

In The Black Guy Dies First, Robin R. Means Coleman and Mark H. Harris track the long history of expendable Black bodies in horror, characters marked for early death, comic relief, and sacrificial logic. But what sticks out beneath that accounting is something far more corrosive: the assumption that Black survival is anomalous. That making it to the end is luck, not strategy.

For women of color, survival is never confined to the final reel. It’s social. Emotional. Structural. It’s learned long before the monster appears: most times, through hypervigilance, pattern recognition, adaptation, and knowing when institutions will fail you. Horror didn’t teach us how to survive; it merely reflects the fact that we already know how. When a Black or Brown woman lives, the question isn’t, “How did she make it out?” It’s what did she already understand about the world that others didn’t?

When a survivor’s skin is darker than a paper bag, the whole equation changes. It disrupts the story. We enter horror already haunted. Looking to root for Black and Brown Final Girls? Jot these down! They’re bloody, brilliant, and mostly ignored if you’re only staring at the usual faces.

The Myth of Purity

Carol J. Clover’s ‘Men, Women and Chainsaws’ gave horror studies a language: the “good” girl who lived, the gaze that shifted, and survival code as chastity. But purity has always been a rigged game. In American Horror, whiteness equals innocence. The blonde, the babysitter, the virgin; moral clarity made flush. Everyone else exists to die for the plot.

When a woman of color appears, she’s rarely allowed ambiguity; she’s too sexual, too angry, too loud, too expendable for us. Surviving isn’t usually in the cards, but when it is, it packs a hell of a wallop.

Survivors No Longer Anonymous

Rita Veder (Angela Bassett in Vampire in Brooklyn, 1995) doesn’t run from the monster. She lets him believe she needs him. Maximillian struts around like he’s the headline, but Rita’s the one actually changing. He’s all leather coat bravado, selling freedom while quietly tightening the leash. Rita doesn’t escape him; she outgrows him. What looks like seduction is really her clocking her own power again, the kind that never needed his permission. He thinks he’s giving her immortality. All he really does is remind her who she’s always been.

Alexa Woods (Sanaa Lathan in Alien vs. Predator, 2004) doesn’t beg for mercy; she earns respect. She survives by paying attention, adapting fast, and refusing to panic. The mark on her skin isn’t a scar; it’s a rite of passage. Once the Predator carves it into her, she’s no longer a Final Girl. She’s something older. Someone who learned how danger thinks, and answered back.

Mindy Meeks-Martin (Jasmine Savoy Brown, Scream 2022) survives because she understands the machinery of horror and refuses to be surprised by it. She knows the rules, the cycles, the nostalgia traps that dress repetition up as reinvention. As a Black, queer horror obsessive, Mindy occupies a position the genre historically denies: the character who names what’s happening while it’s happening and is still allowed to live. Uncle Randy walked so she could run, I guess.

Her survival isn’t rewarded for moral goodness or punished for knowledge. She gets stabbed precisely because she’s right. She warns the room, is dismissed, bleeds for it, and still exits the narrative breathing. Scream has always claimed self-awareness as absolution; Mindy exposes that lie. Knowing the genre doesn’t grant safety, but it does strip away illusion. Her survival reads less like triumph and more like correction: a recognition that Black women have always understood the story they were trapped inside of.

Gail Bishop (Master, 2022) understands that for Black women in academia, danger rarely arrives all at once. It starts small. A comment framed as concern. A question that isn’t really a question. Gail (Regina Hall) and Jasmine Moore (Zoe Renee) move through an elite institution where microaggressions are treated as tradition and isolation is sold as prestige. Jasmine learns quickly that being “welcome” doesn’t mean being safe. The hauntings mirror what the university refuses to name: Black women are expected to absorb discomfort quietly, to doubt their instincts, to keep performing excellence while being chipped away at. What begins as a subtle erasure curdles into real danger. Master doesn’t make it clear if the threat is supernatural or structural, but it insists that both are lethal, especially when no one believes you until it’s far too late…and even then…no one gives a shit.

Aisha (Anna Diop in Nanny, 2022) survives by staying alert in a world that expects her to disappear quietly. A Senegalese immigrant caring for a white family’s child, she moves through domestic space already haunted by memory, by distance, by the cost of leaving a son behind. The horror isn’t just what stalks her at night; it’s the slow erosion of safety that comes with being needed but never protected. Aisha learns to survive because she knows the rules are stacked against her. She’s refusing to vanish and refusing to forget who she’s doing this for.

Karla Wilson (Brandy Norwood) outran the killer in I Still Know What You Did Last Summer (1998), and then the camera straight-up abandoned her. She lived, the film moved on, and Hollywood shrugged. And yet, she’s still here, still standing, still ride-or-die all the way into the 2025 sequel. Survival doesn’t always get a victory lap. Sometimes it barely gets acknowledged.

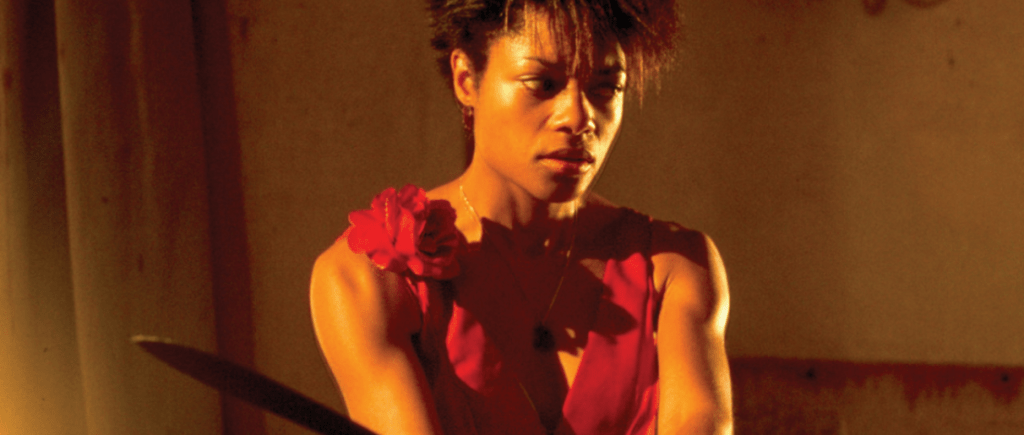

Selena (Naomie Harris in 28 Days Later, 2002) shows us that calm can be lethal in the right hands. Her vigilance isn’t paranoia; it’s experience talking. She doesn’t wait to be reassured, doesn’t assume help is coming, doesn’t romanticize hope. She survives because she understands the situation exactly as it is, and acts accordingly. This is an instance when knowing when to “nope” the hell out of there saves lives.

Brianna Cartwright (Teyonah Parris, Candyman, 2021) doesn’t summon the myth; she’s left dealing with what it turns into. When Anthony gives himself over to it, Brianna doesn’t run. She stays. She watches. She absorbs the fallout. This isn’t new territory for her. She’s already lived through the aftermath of her famous artist father’s suicide, already learned how to hold grief quietly while the world keeps moving. So when the cops arrive, and the story twists, Brianna is once again left with the wreckage; expected to make sense of it, expected to carry it. There’s no clean win here. She holds what’s left because someone always has to. And in horror, that someone is almost always a woman.

The Weight of Being Seen

Every time a non-white woman makes it to the credits, she carries two bodies: her own and the symbolic one. Survival becomes labor. Visibility, work. But it’s also freedom. Because when she walks out breathing, she drags the genre with her.

As bell hooks wrote, “To be truly visionary, we have to root our imagination in our concrete reality while simultaneously imagining possibilities beyond that reality.”

These women don’t simply expand the canon; they dent it. They swagger out of horror’s side door still chewing on the scenery, daring anyone to tell them they weren’t supposed to make it. That’s the real trick: they survive the script and the system that wrote it. They bleed in subtitles, scream in dialects, and turn being seen into its own haunting.

The Final scream now speaks in global tongues, gods, and ghosts. It doesn’t ask permission, and it sure as hell won’t shut up.

The mic’s still bloody, but it’s ours now.

We don’t just make it to the end.

We were already surviving when the movie started.

You can catch some of my other suggestions here!

Leave a comment