By Mo Moshaty

There’s a moment, often far too late, when we are finally permitted to protect ourselves.

Not legally, not practically, but socially.

Home invasion horror has taught us to expect violence at the door. There’s going to be forced entry, broken locks, shattered glass, and a wounded animal. Hoping not, but most likely. But some of the most unsettling films in the genre truly understand that danger rarely announces itself. It arrives politely. It asks to come in. It waits to be offered a drink. It exploits the long pause between discomfort and refusal; that odd space where we’re still trying to be gentile. Because let’s face it, even as children, we’re taught to be polite before we’re taught to defend ourselves.

What these films are truly about isn’t ignorance; they’re about conditioning. About the social scripts that tell us it’s better to be accommodating than to be alert, and it’s better to be kind than be cautious, and it’s better to feel a little uncomfortable than risk appearing rude.

To which I say, fuck the niceties, get out of my house. But this story isn’t about me; it’s about these poor souls to follow. What we’re going to look at is home invasion horror by invitation, where the real breach isn’t the door, but our personal boundaries.

Case Study I: Funny Games (1997)/Funny Games (2007)

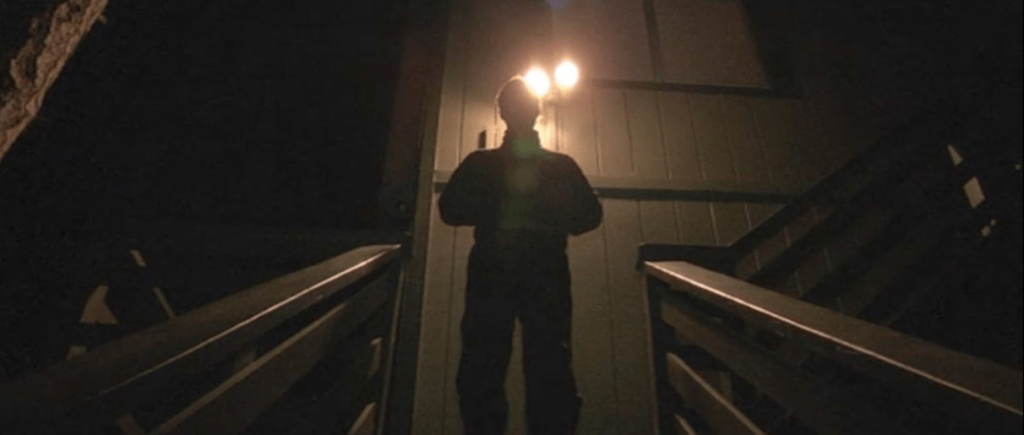

In both versions of Funny Games, the violence starts long before it’s physical. Two young men arrive at a holiday home asking to borrow eggs. They’re well spoken. They’re all in white, clean, calm. They apologize constantly. They smile.

Their threat isn’t force, but politeness stretched to the point of absurdity. Each boundary they cross is small enough to be excused, each transgression softened by manners. The family’s compliance is the scary part because we’ve all been faced with someone we didn’t want to talk to, we didn’t want to be around, and we’re alone with them, so now we have to force the niceties for one of us to get out of there alive.

Director Michael Haneke (1997) understands that politeness can function as a trip. It’s not like the family invited the harm in by trusting these men. They invited them in because refusing it would require them to look less civil. Saying no would mean acknowledging the fear. Acknowledging the fear would be admitting something is already wrong. The killers exploit this hesitation mercilessly. Every act of courtesy reinforces their control. Every “I’m sorry” or “that’s alright” buys them more access, and by the time the family is allowed to defend themselves, when the violence is undeniable, and when the rules of social engagement finally collapse, it’s already too late.

Funny Games isn’t just a cruel home invasion. It’s a film about how thoroughly we’re trained to ignore our own instincts in favor of etiquette. The home isn’t broken into as much as it’s socially dismantled. The door remains open, not because the family is weak but because culture demands restraint before resistance. It’s not about what happens inside the house; it’s how long the house is expected to remain hospitable.

Case Study II: Speak No Evil (2022)/Speak No Evil (2024)

If Funny Games shows us how politeness can fuck us and delay self-defense, Speak No Evil shows us what happens when politeness becomes an obligation.

The danger doesn’t arrive unannounced. It’s invited in. That’s the scary part. Repeatedly and earnestly invited in with smiles, shared meals, and the language of good manners. What begins as an awkward but friendly vacation encounter turns into an escalating series of small discomforts. Death by 1000 cuts; each one too minor and too socially inconvenient to justify refusal. The film understands something really uncomfortable. Most people don’t ignore red flags because they don’t see them. They ignore them because acting on them feels inappropriate.

Every boundary crossed in Speak No Evil, in both versions, is framed as a test of character. Leaving would be rude. Saying no would be ungrateful. Asking people to leave would be inhospitable. Questioning behavior would imply judgment. The hosts never need to force themselves into the family’s space. The family keeps offering it up, convinced that just bearing with it is the price of being decent.

The true devastation of it all is how clearly it maps this slow erosion. The danger accumulates slowly. Every discomfort stacks on top of another until survival feels socially unacceptable. By the time resistance feels justified, it also feels futile. The rules of hospitality have always been obeyed to the letter, and those rules have quietly been rewritten by whoever holds the power.

Unlike Funny Games, where politeness is exploited by strangers who never intend to play fair, Speak No Evil is about how deeply we internalize our responsibility to remain nice. The threat isn’t masked as harmless; it’s masked as an obligation. The hosts don’t need to be charming; they don’t need to be rich, they don’t need to be showering them with gifts. They only need their guests to believe that leaving would say something bad about them.

We’re taught explicitly and implicitly that safety we should wait its turn. That discomfort should be managed quietly. If you’re uncomfortable, keep it to yourself. Don’t make anybody feel bad. Don’t escalate. Don’t be dramatic; causing offence is worse than feeling afraid.

This conditioning isn’t abstract. It’s social training, and it starts early, especially for women. Be polite, be grateful, be accommodating, smile. The message is clear: your unease is less important than maintaining the harmony of the situation, and once that rule is internalized, it becomes incredibly easy to exploit. Violent men prey on this fact with women all the time, on dates that start to go sour, in public spaces where ‘no’ is treated as negotiable, in private spaces where leaving would be awkward, inconvenient, or read as rude. Women are taught to manage men’s feelings in real time: to soften refusals, to laugh off discomfort, to keep situations calm rather than safe, so maybe you won’t kill us.

We’re forced to play nice because the unspoken hope is that if we’re pleasant enough, compliant enough, unthreatening enough, maybe we’ll be allowed to leave intact. That logic is super horrifying for this film because it’s really familiar.

Speak No Evil understands this dynamic because the film doesn’t exaggerate politeness into absurdity like Funny Games; it simply mirrors it. The guests aren’t passive; they’re not unaware, but because everything they’ve been taught tells them that objecting to anything would make them the problem. Their hosts don’t need to threaten violence early on. The social norms do the work for them.

What Speak No Evil exposes is how politeness functions like a leash. It doesn’t delay resistance; it simply reframes it as a cultural and social failure: leaving early is rude, questioning behavior is judgmental. Protecting yourself? You’re antisocial. This is why the film lands so hard. It doesn’t ask us to imagine a new terror; it asks us to recognize an old one. The guests are behaving exactly as they’ve been taught to behave, right up until survival is no longer an option.

Class and the Performance of the “Good Victim”

There’s an unspoken framework holding these stories together: the performance of the good victim.

Politeness doesn’t operate equally across situations or bodies: who is expected to stay calm, who is allowed to be suspicious, and who is believed when discomfort is expressed are shaped by gender, class, and social power. The pressure to remain agreeable often falls hardest on those who have learned that being perceived as difficult, dramatic, or rude comes with consequences.

This is where the good victim narrative does its damage. The good victim is polite. The good victim gives chances. The good victim doesn’t overreact. They don’t cause scenes. They push through discomfort and wait for proof before acting; proof that almost always arrives too late. Survival, in this framework, becomes something you earn by behaving correctly.

Gender sits at the center of this conditioning. Women are taught early that managing other people’s comfort is part of staying safe. Say no, but not too firmly. Leave, but don’t make a fuss. Keep things friendly. Keep things calm. The implication is always the same: if you handle the situation correctly, nothing bad will happen.

But horror keeps returning to the same damn stance: politeness does not protect. It delays. It reassures the threat. It reframes danger as something that must be tolerated rather than escaped. The longer someone performs goodness, the more they are expected to endure in return. The terror in these films isn’t that violence arrives unannounced. It’s that we are taught to wait until fear is socially justified before we act on it.

Case Study III: Creep (2014)

Creep is what happens when politeness is mistaken for patience.

The film’s power doesn’t come from jump scares. It comes from how long the protagonist keeps negotiating his own discomfort. Every warning sign is there in front of his face. Nothing about Josef’s behavior is subtle. He overshares. He lies. He violates personal space. He acts incredibly vulnerable just to remain close, and still the situation continues, because confronting it would require breaking a social contract of niceness.

Creep shows us how deeply we’re trained to tolerate discomfort if the alternative is appearing rude. Joseph doesn’t need to trap his victim physically; he traps him socially. Each moment of awkwardness is framed as a test: Are you patient enough, kind enough, or understanding enough to stick this out? Leaving early would be admitting fear and defeat. Calling out the behavior would mean accusing someone who insists repeatedly that he’s just being honest.

Yes, the escalation is gradual, but it’s not ambiguous. Aaron knows he’s in the shit. Boundaries are crossed in obvious ways, then excused, then normalized. The more accommodating the victim becomes, the more confident Josef grows. Politeness doesn’t de-escalate the situation; it only validates it for him. Every anxious smile, every nervous laugh, every attempt to smooth things over communicates the same thing: you can keep going, it’s all right, I’ll take the punishment.

Creep mirrors real-world dynamics where discomfort is managed internally rather than addressed outwardly, where instincts are overridden by having some sort of social grace. Where people stay because leaving feels super dramatic, embarrassing, or maybe just unfair. What’s horrifying is that the victim knows something is wrong, but even knowing that doesn’t feel like enough reason to act.

Creep strips away the illusion that violence requires some sort of deception. Josef isn’t hiding his instability. He’s counting on the fact that politeness will do the hiding for him. And by the time survival instincts finally override that social conditioning, the situation has already become irreversible. The film is effective because it speaks to how small the distance is between safety and danger. There’s no locked door, no forced entry, no dramatic point of no return. There’s just a series of moments where leaving would have been possible and socially uncomfortable until it’s no longer possible at all.

In Creep, home invasion doesn’t happen at the door. It happens in conversation, in hesitation, and in the decision to be nice just one more time.

Case Study IV: The Guest

If Creep is going to use awkward intimacy to trap its victim, then The Guest is going to use respectability.

David (Dan Stevens) doesn’t arrive asking for patience and understanding; he comes with credentials. He’s polite, composed, and grateful. He knows how to behave. His presence is framed as a courtesy returned; a soldier honoring a fallen comrade, a guest repaying kindness with protection. Hospitality is immediately endorsed.

The social horror here is how quickly politeness hardens into obligation. David doesn’t force his way into the family home. He’s welcomed, encouraged to stay, and praised for his manners. Each act of kindness extended to him becomes harder to revoke. Asking him to leave would be just plain cruel. Questioning his behavior would feel ungrateful. The family doesn’t ignore warning signs because they don’t see them. They ignore them because doing otherwise would violate the rules of hospitality they’ve already agreed to uphold.

This is how social legitimacy operates. David looks right. He speaks correctly. He knows when to say thank you. His violence is excused, minimized, or rationalized because it arrives wrapped in usefulness. He helps, he protects, he fixes problems. The more indispensable he becomes, the more uncomfortable it feels to imagine life without him.

I want to sidebar and say that I feel like we all have one person in our lives that is like this, where they just sort of hang around, do little favors, or do things no one asks them to do, and expect to be treated with an uber amount of kindness just to simply have the proximity held. Tag a non-friend to this article if you want.

Unlike Creep, where discomfort is immediate and personal, The Guest shows how danger can be sanctioned. Politeness isn’t about avoiding offense, but about maintaining order. David’s presence stabilizes the household before it destabilizes it. By the time his threat becomes undeniable, the family has already restructured itself around him.

The Guest exposes how easily safety is outsourced to those who appear competent and controlled. The family hands David authority, and once that authority is granted, withdrawing it becomes socially disruptive and, now, dangerous. This is hospitality as escalation. The door stays open not because anyone’s afraid to close it, but because closing it would mean admitting that politeness, gratitude, and trust were misplaced. David has made himself an essential worker in this household, and he’ll be damned if you make him leave.

When Safety is Conditional

In Funny Games, the test is politeness under pressure; in Speak No Evil, it’s suffering framed as decency. In Creep, it’s the ability to tolerate discomfort without making a scene. In The Guest, it’s gratitude mistaken for trust. Each film stages a situation where danger escalates because acknowledging warning signs would violate several social rules.

What these stories reveal about us is how often safety is treated as conditional. You can protect yourself, but only after you’ve been patient enough. You can leave, yes, but only once fear becomes socially understandable. You can say no, but only after you’ve proven you aren’t overreacting. By the time all of those conditions are met, the danger is already imminent.

Home invasion horror has always been about violated space, but these films shift the focus from doors and windows to behavior. The home stops being safe long before anyone forces their way inside. It becomes unsafe the moment politeness is prioritized over instinct, harmony over boundaries, and appearing reasonable over being alive. These films don’t argue that kindness is a flaw per se. They argue that kindness is often exploited, especially when it’s expected to substitute for self-preservation. How many of us have stayed longer than we wanted to, or smiled through discomfort, or waited for permission to leave? The terror of these films isn’t necessarily the violence itself, but the realization that danger doesn’t always demand entry. Sometimes it just waits for us to keep being nice.

Leave a comment