By Emma Cole

Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and The Omen (1976) both deal with birth and rebirth—literal birthing of babies and insidious plots to birth a new, Satanic world order. Though the children in these films are born very late in spring (both, of course, on June 6), the themes of renewal and transformation commonly associated with spring are prominently featured. The films are definitely in conversation with each other, as well as with the larger societal shift from the beginnings of second-wave feminism in the 1960s to the women’s liberation movement of the 1970s. But the films focus on different stages of pregnancy, birth, and motherhood. Rosemary’s Baby centers the character of Rosemary herself (Mia Farrow) and her pregnancy leading up to the birth of her son. In The Omen, the central storyline is much more concerned with the child Damien as a young boy than his mother Katherine’s (Lee Remick) growing realization that something is wrong with the child. Still, the themes of rebirth and the transformation of women into mothers are central to both films, and they both lead to similarly chilling conclusions.

The earlier of the two films, Rosemary’s Baby, was adapted from Ira Levin’s novel of the same name and released in 1968. Set in New York City, the movie opens with Farrow’s Rosemary and her husband Guy (played with peak smarminess by John Cassavetes) as they tour an apartment building. Guy is an actor who seems on the verge of a big break (as his supportive young wife tells anyone who will listen) and their current residence is a rundown little apartment in a less-than-desirable neighborhood. Rosemary, who is hoping to become pregnant so they can raise a family together, pushes for the new apartment in the Bramford building—it’s close to all the theaters, it’s bigger than the other apartments they looked at, and it’s vacant because the older woman who had lived there died after a sudden illness.

The apartment is almost womb-like, particularly at first before it’s been brightened up with furniture and paint. It’s dark and features a long and narrow hallway that opens up into the living room, the place where a large portion of the action takes place. Director Roman Polanski shoots much of the early scenes in the apartment at low angles, sometimes cutting off characters’ heads, giving the film a slightly oppressive feel. Even before anything strange is revealed, the audience gets a sense that the apartment is gestating something a little odd. There is a room filled with herbs and plants, left there by the previous tenant. This greenery is a nod to new growth, as in Guy and Rosemary’s newlywed relationship. But it’s been neglected, dried out, and withered, an ominous warning for what’s to come.

Rosemary is portrayed as a very modern young woman, despite her seemingly filling a more traditional stay-at-home spousal role. She’s outgoing, bright, self-sufficient, and clearly confident and supportive without being submissive to Guy. Rosemary initiates the first sexual encounter we see between the couple, in a no-nonsense and straightforward way. She’s happy to grab a drink for her husband when he walks in the door, but she’s not setting a fancy table for him. Farrow gives Rosemary an air of insouciance that never veers into naivete. We’re much more likely to empathize with her than we would if she were a gullible pushover when the neighbors, Minnie and Roman Castavet (Ruth Gordon and Sidney Blackmer), introduce themselves to the new couple.

The sudden shift in the power dynamic between the couple sets up the downward spiral of the rest of the film. Guy seems to return to his more submissive role, apologizing for his behavior and trying to endear himself to his wife after growing distant and more focused on his work. But the audience can feel that Guy’s motives aren’t quite as pure as he would like Rosemary to believe: he’s often shown slightly separate from Rosemary, with doorways between them. When they sit together at dinner before trying for a baby, Guy’s face is slightly obscured by shadow, especially after he returns to the table after accepting chocolate mousse from Minnie (which Rosemary is suspicious of, and rightfully so).

When Rosemary falls into a drug-induced sleep after eating some of Minnie’s dessert, we see the true horror of her situation: Minnie and Roman are witches, using Rosemary as a vessel for Satan’s child who will bring about the end of the world. They’ve promised Guy success in exchange for Rosemary’s womb, and Guy agrees. There doesn’t seem to be any reluctance or doubt on Guy’s part, which is why he’s near the top of my list for villainous husbands. For the rest of the film, no matter how much Rosemary is in pain or fearful of the situation she’s in, he does nothing but dismiss her claims as paranoia or madness. Guy is not only complicit in the conspiracy to have Rosemary raped and suffering through a dangerous pregnancy, he seems to be enthusiastic about it since he’s getting fame and success out of the deal.

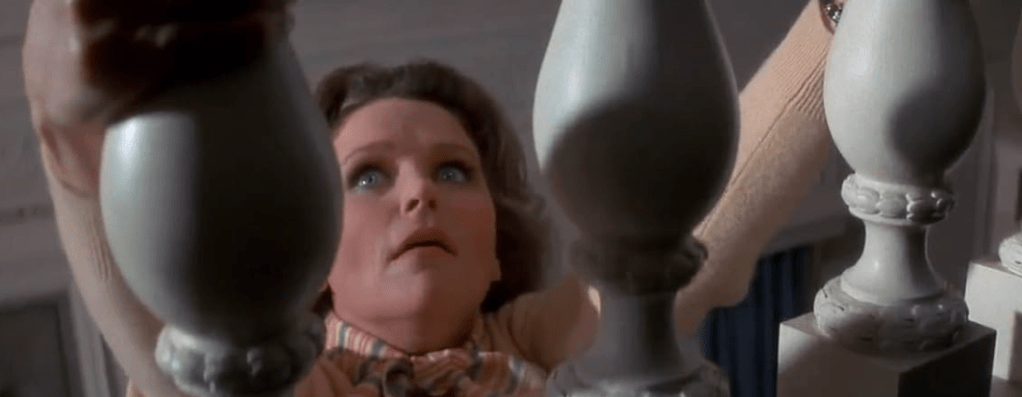

Rosemary is transformed numerous times throughout the film. The demonic pregnancy wreaks havoc on her body, keeping her in constant pain and distracting her from learning more about the Castavets’ supernatural plot. At the same time, she tries to turn over a new leaf, cutting her hair short even though her husband hates it. But the trim seems, like Samson, to rob Rosemary of her agency, and she retreats into herself, obediently following Guy’s suggestions. Even after the pain finally goes away, and Rosemary starts looking healthier as her pregnancy progresses, she still is unable to reclaim her sense of control. Rosemary is often obscured by spindles in stairwells or the elevator gates looking like prison bars, signaling the trap that is closing around her. In a dread-filled sequence, Rosemary tries to escape from the conspirators, and she’s hiding in a phone booth trying to contact another doctor during a heat wave. The oppressive nature of the heat combined with the terror Rosemary feels as her captors look for her creates a nail-bitingly tense scene.

The final transformation is of course Rosemary becoming a mother. Though the Castavets and Guy try to convince Rosemary that the baby is stillborn, she is sure she hears the cries of her child through the apartment walls. Once she finds her way into the Castavets’ apartment and finds out the true nature of her devilish son, we see Rosemary become first horrified and then slowly decide that even though he isn’t the baby she was hoping for, he is still her child. The final shot of Rosemary reaching out to rock the baby’s crib is bleak but at the same time allows Rosemary to regain a sense of control over her life.

While Rosemary’s Baby takes a strong woman and breaks her down to serve a satanic cult, in The Omen, mothers feel almost like an afterthought from the opening scene. Robert (Gregory Peck), the US ambassador to Rome, is consulting a priest in the hospital, and the audience learns that the two men are discussing his stillborn baby. The priest suggests swapping the infant for a child whose mother died in childbirth and says Katherine (Lee Remick), Robert’s wife, never has to know it’s not her child. Since women were often sedated during labor, she has no idea what happened to her biological child. Robert goes along with the deception, not realizing the depth of the conspiracy he’s become entangled with.

The setting soon moves from Rome to the UK as Robert’s assignment changes. He explains to Kathy that it will be great for her and their young son Damien to move to England, and it’s a boost to his career as well. But instead of helping Kathy with more support and opportunities, she becomes even more removed from society, with Damien’s caregivers keeping her from day-to-day decisions. The woman is slowly transformed from the maternal caregiver she is trying to be to a silent bystander in her son’s life.

Kathy is literally shut away indoors as Damien plays outside with his nanny (Kathy Palance), the first indication that in this film, Kathy’s role as mother is taken much less seriously than Rosemary’s. The main focus here is the birth and growth of Damien as he begins to come to power as the Antichrist. As in Rosemary’s Baby, director Richard Donner also uses shadows and banisters, evoking prison bars, to signal Kathy’s trapped nature. Her removal from Damien always cuts her off from making decisions or wielding power within her family.

At Damien’s birthday party, Kathy is envious of Damien’s nanny, oblivious to the dark forces encroaching on their seemingly idyllic life and getting to spend her time raising Damien while Kathy is sitting on the sidelines. But this young nanny is soon dispatched by the hell hound who arrives to guard his young master and compels the woman to hang herself so another maternal figure can take over. (As an aside, a similar scene in the prequel The First Omen is quite effective if you’re familiar with the original film; the dread is amplified as the audience waits for the death they know must be coming.)

When the new nanny, Mrs. Baylock (Billie Whitelaw) shows up, Kathy is relegated to an even smaller role in her child’s life, as Mrs. Baylock begins to prepare the child for his role as the son of Satan (unbeknownst to his parents of course, though we see the beginnings of suspicion creeping in). When Kathy expresses her reservations about the new governess to Robert, he once again undermines her and dismisses her concerns. Kathy struggles to find her place in the new dynamic of the family unit, and when she tries to exert her motherly authority over Damien, telling Mrs. Baylock he needs to attend church, she is punished for her efforts—Damien takes out his anger and fear of the holy place by beating his mother.

The film isolates Kathy even further from the narrative as it progresses, often showing her either on her own with Damien or otherwise separated from her husband. Many shots featuring the entire family (as in the drive to the church) place husband and wife on opposite sides of the screen, with Damien in the middle, the wedge driving the couple apart. Things get worse when Kathy discovers she is pregnant with another child. She’s desperate to abort the baby, as she is worried she’s going crazy with paranoia surrounding her relationship with Damien. Robert denies her out of hand, blaming her behavior on the psychiatric doctor she’s seeing. While the doctor is more sympathetic to Kathy than Dr. Sapirstein in Rosemary’s Baby at first glance, he still upholds the patriarchal hierarchy, discussing the situation with Robert while Kathy is absent, and capitulating to Robert’s demand that Kathy keep the baby.

Ultimately, Kathy doesn’t get to keep the child, because, in one of the most iconic moments of the film, Damien slams into his mother on his tricycle and knocks her over the side of the balcony. Kathy plummets to the ground floor and is sent to hospital with severe injuries. Once Kathy is injured, she’s largely removed from the film, and Mrs. Baylock subsumes Kathy’s role as a mother, transforming the maternal figure from one of compassion and kindness to a harsh and violent protector. Kathy does get a good visual moment when Mrs. Baylock finds her in the hospital to dispatch her for good. Kathy is shown with her sheer shift stuck over her face like a veil, a virgin sacrifice. She gives up her life for her son as mothers are so often expected to do, even if in this case not a willing sacrifice.

These two films show both pre-and postpartum aspects of motherhood, and at the same time explore the transformation women are expected to undertake when they assume the role of a parent. The fears that are often ascribed to new parents are here amplified by the threats the children pose, not only to the women themselves, but to the world at large. The new world order that the secretive conspirators in both films try to bring about comes at a huge cost to Rosemary and Kathy, who are not even given a choice in the matter. In both cases, the men in their lives give them up to the devil’s plans, either consciously or because of the underlying patriarchy to which they subscribe.

Leave a comment