By Stephanie Farnsworth

The original Mass Effect trilogy (2007-2012, and remastered in 2021), produced by BioWare and published by EA, captivated audiences and won plaudits worldwide for its complex branching narrative, where player decisions spanned across three games culminating in a final decision for the player that would permanently alter the future of the Milky Way galaxy. The science fiction series focuses upon the playable character, Commander Shepard, who learns of the imminent arrival of a hybrid species of synthetic and organic beings called reapers, each the size of a very large spacecraft, and collectively set upon harvesting all genetic material in the galaxy, spelling doom for trillions of people.

Throughout the series, player decisions have consequences for other characters and upon the chances of the galaxy surviving the reaper invasion. In the third game of the series, after years of Shepard warning the galaxy of the imminent threat (while being dismissed as a conspiracy theorist and alarmist) the reapers finally arrive bringing inevitable destruction in their wake. Throughout the third game, the player Shepard must forge alliances and treaties with other species in the fight against the reapers – given absolute authority throughout the war, even over decisions about whether to keep certain alien allies sterilised or not.

Mass Effect 3 captures the devastation of this genocide, particularly as the player can witness refugees fleeing to the galactic capital, the Citadel, and seeking hostile responses from local administrators despite their obvious plight, but it also evokes themes of horror throughout its (roughly) 50-hour playtime. Because of the ways in which the body is fully subjugated throughout the trilogy, with player decisions reigning dominion of populations, the game acts as a management system for life. But it also has missions showing bodily horror, through nonconsensual bodily transformations as vulnerable populations are experimented upon by the reapers and by enemy (human) forces, enslaved to do the reapers’ bidding. As a result, the game – and the series more broadly – acts as a work of biopunk, a science fiction subgenre defined by Lars Schmeink as being concerned with bodily manipulations, whether that be zombie viruses, biological warfare, or creating life from body parts (as in the classic Frankenstein: or the Modern Prometheus published by Mary Shelley in 1818). The subgenre routinely evokes themes of body horror, and Mass Effect has a multitude of mutant plotlines through its four games (and undoubtedly within the anticipated fifth game). Perhaps no mission most captures the horrific ways in which the body is subjugated than ‘Sanctuary’ taking place toward the end of the final instalment of the trilogy.

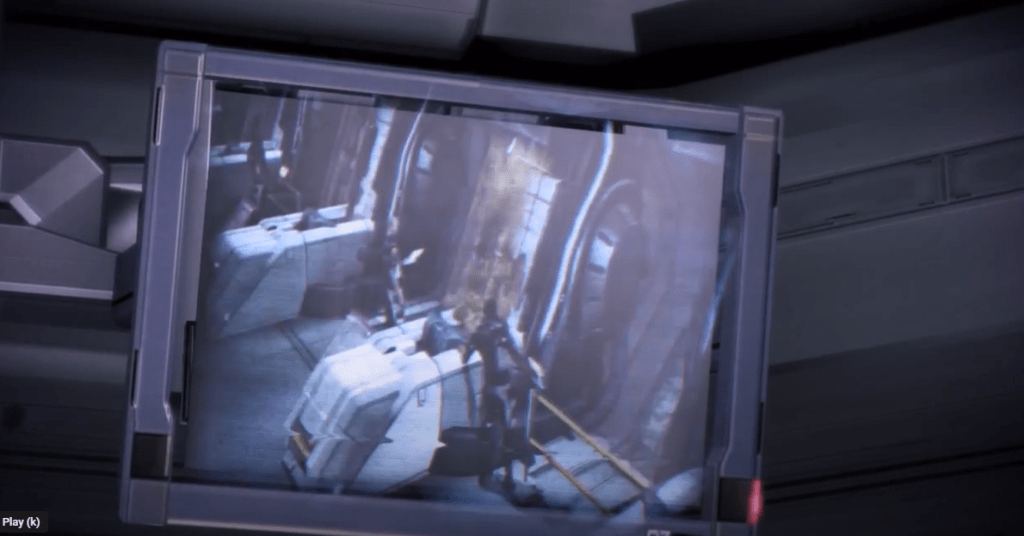

Advertisements for Sanctuary frequently appeared across the game at this point, and it had been depicted as a utopia with the player able to listen into several citizens previously discussing whether to leave for the safety it offered. After several critical losses to the reapers, a signal led Shepard’s confused team to Sanctuary, which previously had been advertised as a safe and secure space for refugees fleeing the war. When the player arrives, however, Sanctuary appears deserted as Cerberus soldiers flee and the building lies in ruins. As Shepard’s team makes their way inside, they are confronted with alien reaper forces – mutated aliens that have been transformed into zombie-like soldiers – and must battle their way through this mystery. Several video logs left reveal the true horrors of Sanctuary; Cerberus ran the enterprise, presenting it as a safe space for refugees but once people showed up, they were processed, taken to a hidden underwater laboratory, and experimented on, with most either dying or being transformed into husks, the zombie-like reaper soldiers that lose all autonomy and do the bidding of their creators. The player sees video footage of these transformations, unable to help the refugees that are thrown into glass cylinders and, despite their best efforts to break out, are transformed into wasted, corpse-like soldiers. The horror from Sanctuary comes from several different elements: the unusual lack of agency for the player, the masquerade of the sanctuary as a safe space for vulnerable people, the body-horror transformations of the refugees who, once husks, must then be killed by Shepard, and the unusual and uncanny setting of the abandoned hidden unwater laboratory where refugees are taken after processing.

For games scholar Joseph Laycock, games – video and analog – may attract a polemic discourse but “these games inform questions of meaning, identity, and morality1” , and there are real-world implications for the depiction of the treatment of refugees within the science fiction series. The laboratory within Sanctuary, and specifically the pods where the refugees have been held and transformed, evoke the horror of the eugenics movement – a movement that dominated twentieth-century politics (but still has influence in the twenty-first century). Eugenics also spread far beyond European borders, as Canada – where the games development company that created Mass Effect is based- implemented policies of sterilisation against Indigenous women and girls who are still seeking justice.

Additionally, while the ‘30s and ‘40s are renowned for the atrocities of the Nazis across much of Europe, during World War II, Japan commissioned Unit 731 to conduct biological warfare through experimentation. For those who entered Unit 731’s facility as test subjects, their life expectancy was merely one-month.2 A former officer states that “we knew the prisoners would be used in experiments and not come back”3. The reason that Unit 731 was allowed to exist was due to the fact that “…medicine was treated by the Japanese as being equal in importance to guns and shells in contributing to military performance”4. Japan identified a key vulnerability during wartime: the threat of the disease. Perhaps this was no more keenly felt than in Europe with the outbreak of flu in 1918 that claimed the lives of roughly 50,000,000 people.

Soldiers were at greater risk from disease due to close quarters and a lack of sanitized conditions than they were of bullet wounds. Japan forged ahead with ethically dubious research that was designed to make medicine a helpful aid to its soldiers during wartime, but the establishment of Unit 731 saw a shift to the idea that medicine could also be a weapon against its enemies. The Unit focused on pushing the human body to the limits – and broke those limits to learn more about death. This involved dissections on live subjects without anesthesia, fatal experiments on babies by deliberately triggering frostbite, and taking so many blood samples from prisoners that “some of the victims became progressively debilitated and wasted”.5

While the motivations may be different, Cerberus believes that refugees must be subjugated and consumed within the war machine to support their ideological battle against Shepard. With Cerberus, we see similar acute bio-exploitation as people are rapidly experimented on and turned into husks, almost as soon as they arrive at Sanctuary. As transhumanist scholar Thweatt-Bates states: “The notion that humanity might transcend or technologically transform its own nature collectively, rather than sporadically and individually, in these intellectual and historical precursors to transhumanism brings with it the specter of eugenics”6.

For Lars Schmeink, creator of the term ‘biopunk’, states: “Human lives, in the sense of biocapital, become commodities that need to be managed, their economic value determined through their biology, in the sense of a posthuman being-animal or being-machine”7. Humans have a closer relationship to biotechnology than at any point in history, as well as a closer relationship to technology more broadly. Biometrics are used for everything from watches to track our health to shopping centres designed to ensure we pass through certain shops and entrances. This demonstrates the idea that we are becoming machines which posthumanist Rosi Braidotti refers to as ‘radical neo-materialism’8.

Human lives have more ways than ever before in which they can be managed or subjected to nefarious ideologies and refugees, due to their displacement and the hostility domestic populations often harbor to new arrivals, are particularly vulnerable to exploitation. In a biotechnological age, there will be attempts to erect concrete borders to control a changing landscape and this will manifest in the form of biological determinism – through false techniques such as x-raying migrants to ascertain their age9 which is already happening in countries such as The United Kingdom. Questionable technology is also being deployed along the borders of the United States,10 as facial recognition software – prone to racial biases and mistakes11 – is being utilised across 57 airports.

While biotechnology has often been deployed as an enforcement tool by governments, the possibilities of technology have been used by populists and the far right to fan the flames of hatred against minorities. During the presidential campaign of 2024, Donald Trump alleged that his Democrat rival, Kamala Harris “wants to do transgender operations on illegal aliens that are in prison. This is a radical left liberal that would do this.12” Brodwin asserts that the uncertainties emerging from biotechnological developments change how the body is conceptualised and categorised as the body is an arbiter of political relations13, leading to alarmist fears that biotechnology can disrupt normative societal ideals, while simultaneously being used to enforce those very same normative and oppressive ideals that are supposedly under threat.

The Mass Effect trilogy allows players to act as enforcers or disruptors of these normative ideals through a science fiction imaginary that allows the player almost total power of negotiations with populations and to shape the makeup of the galaxy. Within the series, the player can choose to keep an oppressed and racialised population sterilised, to commit genocide against several other populations that may be viewed as expendable in the context of the reaper war, can use data obtained through unethical body experiments, can torture a subject in custody for information and can work with and befriend a scientist responsible for keeping the krogan population sterilised. Bioethical plotlines are represented across the series, but the interesting deviation with Sanctuary is that the player has very little agency throughout the mission. They are not in control of the experiments or faced with decisions over the subjects, instead, they are powerless and can only witness the horrors performed on the refugee population via the left behind videos, and then must ultimately kill the refugees-turned zombie-husks that remain. The lack of power for the player is a change of pace from the rest of the series, but it is another key element to contribute to the themes of horror as the player can do nothing of worth to help the refugees while navigating Sanctuary and its hidden underwater laboratory.

One of the key ways in which horror resonates with audiences is by how it “channels social fears”14. The horror genre is a body genre15 and ‘body-horror,’ greatly overlaps with the science fiction genre, the latter, of course, being much broader. In body horror, some sort of anomaly – whether brought on by nature, scientific experimentation, divine punishment, or the environmental impacts of war – threatens the safety of (normal) humanity”16. The scientific experimentation of the refugees highlights the potential exploitation of vulnerable populations, but adding to the horror is the fact that the refugees are turned into husks, which act as zombified people and pose an incredible danger to the communities they came from, acting as agents for the reapers. The player cannot progress throughout the game without facing the husks in combat, knowing who they once were. The popularity of horror (including body horror) is that it “derives from its transgressive nature – from the fact it can deal in matters often left out of other genres or considered too extreme, maybe even harmful”17. Through the lens of sci-fi horror, players can be confronted with fictionalised tales of subjugation, experimentation, and oppression that draw directly upon the real world, and so Mass Effect evokes historical atrocities such as the Nazi concentration camps and the experimentations of Unit 731 while striking a chord with the loaded political language and biotechnological potential that now dominates cultural discourses over 18 years since the released of the first game of the series. Gothic scholar Halberstam argues there is “a peculiarly modern emphasis upon the horror of particular kinds of bodies”18 and the rise of biotechnology as a key site of capitalism offers new imaginaries of the ways in which the body may be made a subject. The rise of populism has seen a backlash against normativity with ramped-up rhetoric against transgender people, women’s bodily autonomy, and liberty for refugees across much of the West. Branching sci-fi horror narratives such as Mass Effect can capture the desperate situation of refugees moving from hostile system to hostile system with no hope of a utopian rescue while warning against the dystopian power of having absolute control and authority over vulnerable people. While gaming fans wait for the release of the fifth Mass Effect title, increased raids and detentions are taking place against migrants across the United States, and the United Kingdom has plans to send rejected asylum seekers to third-party countries. Mission Sanctuary is the stuff of nightmares, but it is an example of horror that forms part of a cultural discourse reflecting upon (comparatively) recent history and the precarious position of refugees under unwilling systems of control. Horror games have never been just for fun; they’re crucial places of discourse for our very worst fears.

- Laycock, J. (2015) Dangerous Games: What The Moral Panic over Role-Playing Games Says about Play, Religion, and Imagined Worlds. California: University of California Press, p.22. ↩︎

- Gold, H. (1997) Unit 731 Testimony. Tokyo: TUTTLE Publishing, p.31 ↩︎

- Gold, H. (1997) Unit 731 Testimony. Tokyo: TUTTLE Publishing, p.27 ↩︎

- Gold, H. (1997) Unit 731 Testimony. Tokyo: TUTTLE Publishing, p.20 ↩︎

- Gold, H. (1997) Unit 731 Testimony. Tokyo: TUTTLE Publishing, p.31 ↩︎

- Thweatt-Bates, J. (2012) Cyborg Selves: A Theological Anthropology of the Posthuman. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing. [Online], p.44 ↩︎

- Schmeink, L. (2016) ‘Utopian, Dystopian, And Heroic Deeds of One’, Biopunk Dystopias Genetic Engineering, Society and Science Fiction. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, p.226. ↩︎

- Braidotti, R. (2013) The Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity Press, p.95 ↩︎

- https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/oct/15/priti-patel-theatening-use-x-rays-verify-asylum-seekers-age ↩︎

- https://www.cbp.gov/travel/biometrics ↩︎

- https://www.aclu-mn.org/en/news/biased-technology-automated-discrimination-facial-recognition ↩︎

- https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/trumps-transgender-operations-illegal-aliens-debate-claim/story?id=113584635 ↩︎

- Brodwin, P. E. (2000) ‘Introduction’ in Biotechnology and Culture: Bodies, Anxieties, Ethics, Brodwin, P. E. (eds.) Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, p.7. ↩︎

- Reyes, X. A. (2016) ‘Introduction: What, Why and When is Horror Fiction?’, Horror: A Literary (Xavier Aldana Reyes, eds.). London. The British Library, p.12 ↩︎

- Williams, L. (1986) ‘Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess’, Film Genre Reader III, Barry Keith Grant (eds.). Austin: University of Texas Press, p.143. ↩︎

- Morelock, J. (2021) Pandemics, Authoritarian Populism, and Science Fiction. Oxon: Routledge, p.2 ↩︎

- Reyes, X. A. (2016) ‘Introduction: What, Why and When is Horror Fiction?’, Horror: A Literary (Xavier Aldana Reyes, eds.). London. The British Library, p.12 ↩︎

- Halberstam, J. (1995) Skin Shows: Gothic Horror and the Technology of Monsters. Durham: Duke University Press, p.3. ↩︎

Leave a comment