by Bash Ortega

Xenomorph biology is complex: their blood is made of acid, they have an extendable pharyngeal jaw, and are protected by a hard exoskeleton. However, we know very little about their genetics and mechanism of reproduction. We can look to the animal kingdom to find some possible answers to xenomorphs’ sex lives!

Xenomorphs have a complex life cycle. Facehuggers emerge from ovomorphs (eggs) and lay a fetal chestburster inside a host until it exits the host’s body to mature. The mature drones (and sometimes queens) then lay eggs and the life cycle repeats. The most similar animal in terms of life cycle is the subclass Eucestoda (tapeworms). For example, the pork tapeworm’s eggs are eaten by pigs, where they are dispersed and implanted in muscle tissue. The larval stage of the tapeworm grows in the tissue until it is eaten by a human then, the worm makes its way to the digestive track where it anchors itself. From here, the tapeworm feeds on its host’s food, and lays its eggs which enter the environment when the host poops. Like the xenomorph, the cycle repeats from the eggs. Tapeworms have both male and female genitalia and are capable of reproducing both sexually and asexually. This is a possibility for xenomorphs, but most evidence points to the species being unisexual (having only one sex) rather than hermaphroditic (having fully formed sets of both genitalia).

The simplest solution to how xenomorphs are able to reproduce is that they are parthenogenic. Parthenogenesis is an asexual kind of reproduction in which a female can have babies without needing to be fertilized by a male. The most famous example is probably the “lesbian lizards” – the New Mexico Whiptail – which is an all female species of lizards that produce asexually. Asexual reproduction has benefits because it can produce more offspring more quickly. If every member of a species is female, then they can all bear young, compared to species that produce sexually, in which half of the members, the males, cannot bear young. Being able to produce lots of offspring would be very beneficial to a species like the xenomorph whose main goal is the propagation of their species.

One drawback to asexual reproduction is that it lacks genetic variation. However, not all parthenogenetic offspring are clones of their mother. Some animals, such as snakes and birds, use a ZW system of sex determination as opposed to the XY system that is used in humans and other mammals. In XY sex determination, XX offspring usually develop into females and XY offspring develop into males. However, in the ZW system of sex determination, ZW offspring develop into females and ZZ develop into males. The females have the different set of chromosomes also known as the heterozygous pair. Because female snakes have heterozygous chromosomes, when they reproduce through parthenogenesis, they can have both male and female offspring!

Xenomorphs also have a hive structure in which a queen is responsible for laying eggs, and the rest of the members of the hive work to protect her. The insect order Hymenoptera (ants, bees and wasps) are well known for their hive structure, and can perhaps give us a clue to xenomorph biology. Unlike the animals discussed earlier, bee sex is determined by the number of chromosomes an individual has. Males are haploid, meaning that they only have one set of chromosomes, whereas females are diploid, meaning they have a pair of each chromosome. About 20% of the animal kingdom use a haplodiploid mode of reproduction! Haploid males only emerge from unfertilized eggs, and become drones whose sole purpose is to mate with the queen of another colony. This is not to be confused with the xenomorph drone, which is a life stage rather than its role in society. The Queen bee’s job is to mate with males from other colonies to bring genetic diversity back to her home colony. She is usually the only egg layer in the hive. Worker bees are females that build and tend the hive and only lay eggs in extreme circumstances. Adult, non-queen xenomorphs are also known to lay eggs through eggmorphing. Could it be possible that this is a symptom of stress? Many of the xenomorphs seen in the films are without a hive, putting the alien in a less than ideal situation compared to its preferred social structure.

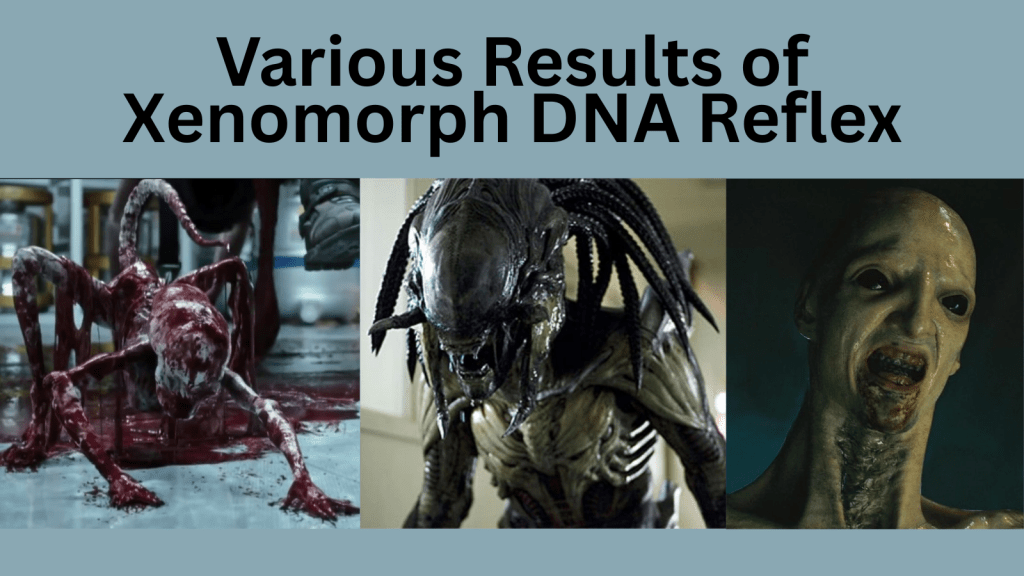

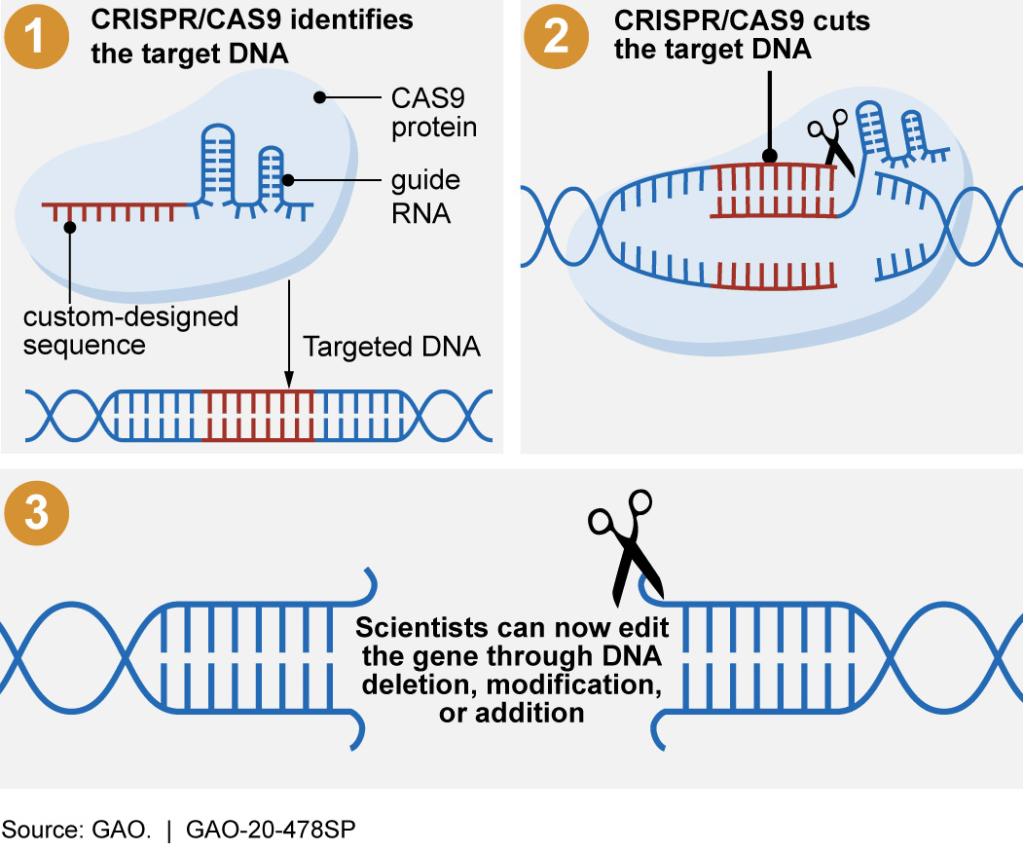

Alien queens do not appear to reproduce sexually like hymenoptera and may only get little genetic variation from parthenogenesis, so where do xenomorphs get their diversity from? We know that the facehugger implants a fetus into its host where the fetus then undergoes the xenomorph DNA reflex. However, it is not understood how this reflex works. It could be similar to CRISPR, which is a method through which bacteria incorporate viral DNA into a specific locus into their genome as an immune defense mechanism. Scientists have learned from bacteria to use CRISPR for gene editing, which allows them to cut the DNA and either remove or add sequences.

All of these comparisons can only give us an idea of what might be happening with xenomorph biology and sex determination. As you can see by looking at the animal and bacterial worlds, sex is much more complicated than just the human conception of XX and XY chromosomes, and we’ve only scratched the surface. The societally popular idea of sex doesn’t even apply to a lot of humans, as there are plenty of intersex people, including those whose chromosomes don’t apply to their gender assigned at birth! We are also able to change our secondary sex characteristics through surgery and hormones even after our bodies have developed. Maybe trying to apply human conceptions of sex to a genetically complex species such as the xenomorph doesn’t even make sense at all!

Leave a comment