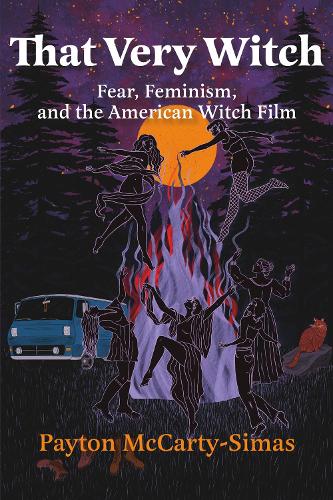

The witch has always been more than a Halloween mask or a folkloric cautionary tale: she is a cultural barometer, a figure we burn, resurrect, and rebrand depending on what haunts us most. In ‘That Very Witch: Fear, Feminism and the American Witch Film’, Payton McCarty-Simas traces this shifting icon across history, cinema, and politics, revealing how she continues to embody our deepest anxieties and fiercest rebellions. It’s a work of nonfiction that blends scholarship with bite. We sat down with McCarty-Simas to talk about witches on screen, feminism and Satanic Panic, and why the witch remains one of the most dangerous, and necessary, figures in our cultural imagination.

You’ve written about conspiracy culture, and now you’re diving broom first into witches. Where’s there a single film scene or moment when you thought, “Yes, this is where I want to plant my academic flag”?

I think the connective tissue in a lot of my work comes from my attraction to the supernaturalism that runs just under the surface of American culture. Americans are a wonderfully, weirdly paranoid bunch with a really singular spiritual history, and our neuroses come out in all kinds of ways both personally and politically. Conspiracism and mysticism are two different facets of that. I’ve always been witchy, but my interest in witches on screen as an academic came out of a pattern, a repeated image that I noticed during Covid that seemed to touch on this particular brand of supernaturalism: At the end of a particular batch of films from the 2010s, flicks like The Witch, Suspiria, and even Midsommar, witches were smiling instead of being burned at the stake. That smile captivated me, and I’ve been working to explain it ever since. How did this evolution happen? Why now? What did it take for us to get here?

In That Very Witch, you covered decades of cinematic history. Were there any eras where you thought the witch had really hit her stride, and any place they became typecast?

The birth of the witch as a real cultural powerhouse with an identifiable aesthetic beyond the pointy hat and the broom comes in the mid-1960s alongside the birth of New Hollywood. I’m not alone when I say that the late ‘60s and early ‘70s was just one of the most creative and fruitful moments in the entire history of cinema, but something I like about it is the odd ways high and low culture were interacting. The cinematic witch of this moment–– part of something called the occult revival, a renewed interest in the occult and the New Age–– is a really good example of this confluence. You see her everywhere, experimental film, big-budget prestige film, pornography, you name it. At this point in history, as the censorship code is falling apart, these avenues are allowed to overlap and engage with each other in really fascinating ways in movies like these, like Rosemary’s Baby or The Devil in Miss Jones. And the witch is a force to be reckoned with in all of them, overtly associated with the Women’s Movement, capable of making change.

Of course, part of my project with this book is to look at the ways that film, like politics, works in cycles, and so as we move from Carter to Reagan and hippies’ interest in New Age spirituality gets replaced by what was eventually called the Jesus Revolution, the witch fades into the background in horror. She’s more of a stock character, often verging on the cartoonish. There’s a sequel to Rosemary’s Baby from 1976 that captures those shifts really well. The witch didn’t really get her groove back after that until the ‘90s.

You’ve mapped witches against waves of feminism, which is no small feat. Was it difficult to keep the analysis from turning into one long political lecture while still doing justice to those cultural shifts?

This is such an interesting question because for me politics and pop culture are two sides of the same coin. My approach to film history and criticism is to try and really give people a sense of the context of a film, the kinds of associations people might have made, the things that would have been keeping them up at night–– which is especially important to horror. We can’t really understand what makes Psycho so seminal without understanding the role censorship played up to that point. Yes, the shower scene is absolutely shocking, but American audiences had never seen a flushing toilet on screen before either. The ambience of the film is just as risqué as the content. To write this book, I drew on articles and sources from dozens of publications–– novels and nonfiction books, academic journals and the Playboy archives––read hundreds of movie reviews, and watched hundreds of movies of all kinds, from Rocky to Deep Throat to Hocus Pocus. I try to draw out the politics that already exist under the surface of these pop objects, draw out the vibe of a particular moment to help us understand what they meant in context and how those meanings shape the trajectory of cinema history as well as reflect the trajectory of our politics. Maybe I’m just a history nerd, but striking that balance was important to me, and it seems to be working pretty well for folks. I’ve had horror buffs tell me they didn’t know a lot of the political history, and witches tell me they didn’t know any of the film history. If we taught history to kids with more of a cultural studies lens, with an eye towards storytelling as a way to explain why things are the way they are, I think we’d all learn a lot more.

The witch is the icon, the villain, the victim, or all three before the credits even roll in most films. What’s the one thing you wish people would stop getting wrong about witches?

Oh boy! Well, at the moment we’ve re-entered a period of conservative cultural backlash and that means feminism is back in the crosshairs. In the book I argue that in periods of backlash the witch loses much of her power to frighten and becomes more of a comic figure, less sexually powerful and more cartoonish, often a hag. Having just seen Weapons… that thesis seems to be bearing out pretty well today. Witches are representative of feminine power across every iteration, from kids movies to horror movies. I want everyone to remember that humor is just as powerful as fear, and when we’re being instructed to laugh at a witch on screen, that image is doing a lot of work to undercut women’s power consciously or unconsciously. Follow the rage on screen, and you’ll usually find empowerment. Follow the laughter, and you’ll find the backlash, at least in witch movies.

From the Satanic Panic to the 2024 election, the witches had to survive some wild political weather. Which most surprised you in how it reshaped her image?

Speaking to the previous question, I was really surprised to find that in moments of conservative retrenchment the witch actually becomes less frightening. It’s counterintuitive, isn’t it? During the Satanic Panic, you’d expect witches to be front and center in horror, but that’s not the case at all. She enters the realm of comedy with things like The Witches of Eastwick. That was really clarifying for me, learning how the rhetoric of antifeminist backlash undercuts feminism through condescension and dismissal rather than pure anger or fear, because to be frightening is to be powerful.

Photography courtesy of Foks Lo (2025)

Riot Grrrl meets witchcraft feels like a perfect playlist. How do you think that punk feminist energy showed up on screen, and do you think it still has a pulse in today’s horror?

This is probably my second favorite era of witch movies for that exact reason! It’s such a natural pairing and so satisfying. Plus the style is to die for. The link between Riot Grrrl, Third Wave feminism, and witchcraft is anger. Women and girls were fed up being put down by the nineties, and they had been raised by women who already had the tools of the Second Wave to help them. They were armed with knowledge and pissed. Movies like The Craft really capture that combination perfectly, and there are absolutely filmmakers channeling that today as well! The first people that come to mind are the more DIY folks like Alice Maio McKay, Grace Glowicki, or Dylan Mars Greenberg, but on a bigger scale Coralie Fargeat is kicking ass on this front. There’s so much satisfying outsider feminist art to go around at the moment across the board, even if especially given the backlash women and queer folks are facing.

Did you stumble across any witch films that made you think, “Why is NOBODY talking about this?” OR “How could anyone have forgotten_____?”

Oh my god absolutely. Part of what I try to do in this book is analyze the low budget flotsam of any moment with as much depth as the big ticket witch movies. Overtly commercial filmmaking, whether it’s exploitation in the ‘60s or straight to VHS schlock in the 80s, is a great litmus test for what people think is trendy or salient to an era’s culture. In terms of less well known titles, I’ve been repping Romero’s Season of the Witch and Eiichi Yamamoto’s Belladonna of Sadness to everyone. Also The Devonsville Terror, which doesn’t get the love it deserves. Oh! I’m also a huge fan of Color Out of Space, but that one’s more of a hot take. The other great thing about sharing this book with people, though, is that a lot of people tell me that they’re finally going to catch up on things they missed. Lots of people haven’t seen Rosemary’s Baby!

As a programmer and a critic, has all of this witch history changed the way you feel when you see her pop up on screen now?

Honestly I feel a deep attachment to the witch on screen at this point, so when I see a witch done dirty it really makes me sad. The end of Weapons was really challenging for me to watch because it comes with so much political and symbolic baggage once you have an understanding of the history of this character. Conversely, I do get a lot of satisfaction when I see a cool witchy set up to do something different than what’s come before. I mentioned Alice Maio McKay earlier–– her latest film, The Serpent’s Skin, is a witch movie a la Charmed and it’s so warm and enjoyable because she really frees herself up from the baggage of a lot of witch lore. There’s so much we can do with witches, and it’s affirming to see people avoid the stereotypical trap that the culture seems to be on the brink of falling into again over the course of this decade.

What’s your personal pick for the most deliciously feminist witch moment in cinema, and why does it still give you that little spark of “hell yeah!”?

Well, the late ‘60s are a good option here – and the filmmaking is just so phenomenal – but I’d say that it has to be the 2010s. That so-called “elevated” horror moment where A24 was just churning out witch movies, it’s so deeply satisfying. I was a teen watching these movies come up, and the excitement was palpable. The gifsets were rockin. Plus, in a certain sense, these films are the most radical in their depictions of feminine rage. Nothing makes me smile as wide as the end of The Witch. We’re living deliciously! Hell yeah!

Your incredible work shows how much you appreciate horror for both its guts and its brains. What’s your personal approach when critiquing horror in cinema? Are you looking for thematic depth first, or do you just let the blood hit the lens and see what sticks?

That’s so kind of you to say, thank you so much! I do think since I think of things in historical and political terms I generally go in thinking about themes first. There are absolutely films that I enjoy on the level of narrative or effects or vibe that are completely ruined for me by their politics. At the same time, just because a movie’s message is conservative – which is incredibly common in horror – doesn’t mean I don’t enjoy it on its merits. I love a good gorefest no matter who’s doing the slicing and dicing, I’m just gonna acknowledge where they’re coming from too. For example, I love Terrifier. I think those movies are incredibly innovative. I absolutely loathe The Neon Demon. I found its use of queer tropes straight up offensive, and that was made worse by the fact that it was the kind of movie that telegraphed its “arty” status. It all depends on how the movie is walking and talking, where it’s coming from and what it seems like its goals are.

In terms of my writing, I try to keep questions of opinion out of it as much as possible. ”Bad” movies can make for fascinating and generative analysis. “Good” movies can, to misquote John Ford, be boring as shit. I think my job is to bring out meanings and situate things in their context. I avoid auteurist analysis when I can, too, because to me everyone is picking up on trends and anxieties in the culture and film is such a collaborative medium it’s more productive to look at things in that broader sociological way.

Horror means wildly different things to different people. For some, it’s a comfort blanket, some adrenaline rush, a social commentary, or simply pure nightmare fuel. What does horror mean to you, and how has that definition evolved over your writing career?

Stephen King has a great line about horror: People write it so they don’t have nightmares. Horror is both something I go to when I’m having a rough day (next time you have a breakup try Audition on for size) but it’s also endlessly intellectually exciting. It rewires your brain so the nightmares you have in your sleep feel more like haunted houses to explore than shades tormenting you. I’ve been writing criticism for almost half a decade now, and the longer I spend in this space and this community, which is so warm and supportive and damn smart, I have the privilege of more context. I get to watch the kinds of histories I research in the past play out in the present, both with witches and elsewhere. It’s such a treat. The adrenaline doesn’t hurt either.

What can we expect next from Payton? Anything new and exciting in the works?

Well it’s been a crazy summer— I just got back from being a part of the Cheval Noir jury at Fantasia and I’m still touring with the book, plus I’m in the middle of the programming process for MIX NYC and Femme Filth at the moment, plus I’m catching up on covering the summer releases with Rue Morgue and elsewhere. Beyond that though, I’m developing another book idea at the moment that I’m really excited about! Hopefully I’ll have some news on that soon… Beyond that I’m writing a chapter for a book on Phantom of the Paradise at the moment and putting the finishing touches on a couple of academic articles expanding on elements of the witch that I didn’t get to cover in the book. There’s so much I want to write about, and I’m so grateful that I have the chance to do it!

Payton McCarty-Simas is an author and editor based in NYC whose work has appeared in The Brooklyn Rail, Film Daze, Bright Lights Film Journal, and Horror Studies among others. They received their MA in cinema studies from Columbia University, focusing their research on horror film, psychedelic film, and conspiratorial thinking. That Very Witch is their second book.

Leave a reply to 5 Must Read Horror Articles 1 September 2025 – This Is Horror Cancel reply