By Ray Walton

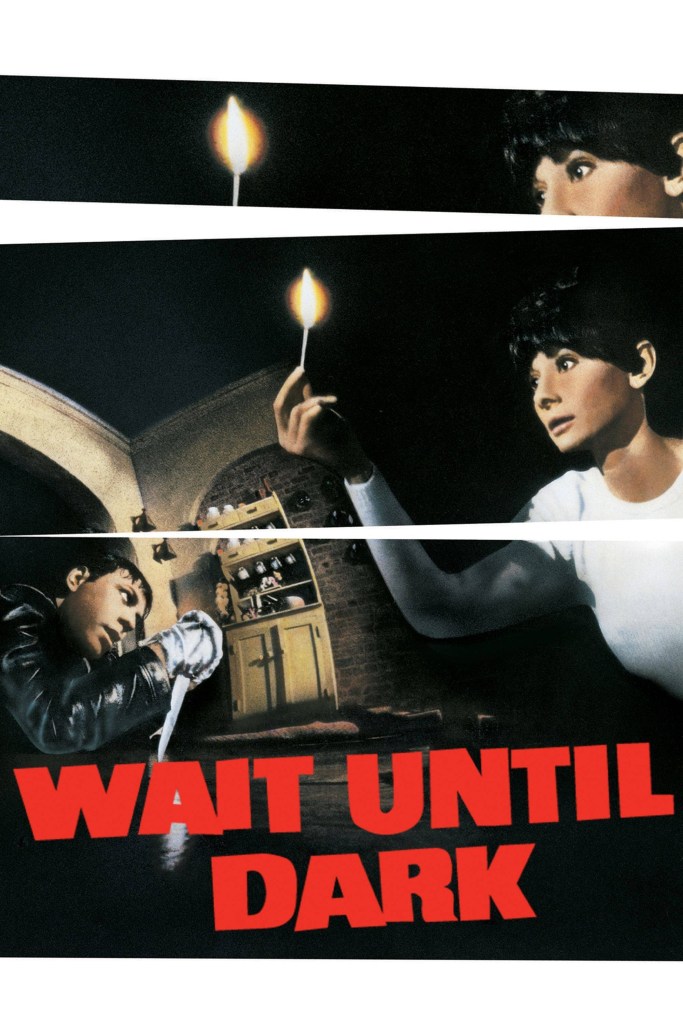

Wait Until Dark (1967) Director: Terence Young ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐.5

A recently blinded woman is terrorized by a trio of thugs while they search for a heroin-stuffed doll they believe is in her apartment.

Released in 1967, Wait Until Dark emerged at a turning point in psychological thrillers, when domestic space became a site of escalating, bodily danger rather than passive suspense. Adapted from Frederick Knott’s stage play, the film retains a theatrical structure — most of its action unfolding inside a single apartment, but uses that confinement to devastating effect.

Arriving in the late 1960s, a decade increasingly attuned to vulnerability and violence within everyday life, the film strips safety from the home entirely. Its tension comes not from spectacle, but from proximity: who controls space, who controls information, and who is underestimated. The result is a thriller that weaponizes claustrophobia, silence, and perception, and builds toward one of the most nerve-racking finales of its era.

This film absolutely lives up to its reputation as a stressful ride. Because it’s adapted from a stage play, you can feel that structure immediately; most of the story takes place inside Susy’s apartment, with characters constantly entering and exiting the space. Rather than feeling limiting, that staginess works to the film’s advantage, creating a claustrophobic atmosphere that traps both the viewer and Susy.

One of the most striking elements is how the film refuses to underestimate Susy. The men targeting her are repeatedly caught off guard by her heightened awareness, particularly her sense of hearing. As someone on the autism spectrum, that resonated deeply with me, the way perception can be sharpened, sometimes to an uncomfortable degree, and how that awareness is often dismissed until it becomes undeniable.

While Audrey Hepburn and Alan Arkin are rightly praised, Richard Crenna deserves far more recognition here. His performance as Mike Talman is layered and complicated, pretending to befriend Susy while working with Roat to retrieve the doll, yet developing genuine sympathy for her along the way. That balancing act is difficult to pull off, and Crenna manages it with remarkable subtlety.

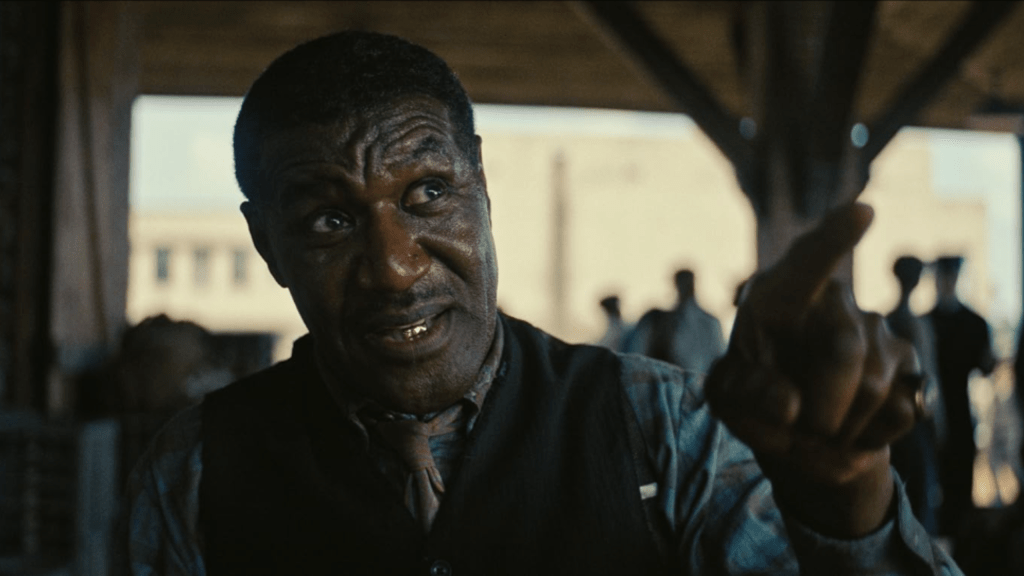

And then there’s the ending. Alan Arkin is legitimately terrifying, completely stealing the film in its final moments. Few scenes have made my heart pound the way this climax did. This may be Audrey Hepburn’s only horror film, but it’s an unforgettable one.

Why tonight?

Because this is a film that weaponizes silence, and winter nights make every sound louder.

Leave a comment